Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

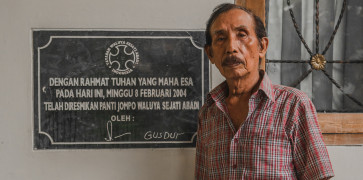

View all search resultsWaluya Sejati Abadi's last political prisoner returns home

Lukas Tumiso is the last person left in Panti Waluya Sejati Abadi, a nursing home for former political prisoners. In part one of our interview, he told us of his wild days following his release from the forced labor camp in Buru. In part two, he discusses an encounter that changed his life and the legacy he wants to leave behind.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Part 2. Returning home

Lukas Tumiso beckons us inside, past the deserted hallways of Panti Waluya Sejati Abadi. Rows of beds lay unused in its rooms. Atop each one is a picture of a former resident, smiling and at peace. If not for the smell of stew coming from the kitchen, one could easily mistake the house for a small museum.

He is reorganizing the library. Stacks of books are littered around the nursing home, as are faded pictures of friends and families. Showing off his copies of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Buru Quartet, the 81-year-old smiles proudly. He had, after all, smuggled these manuscripts out of the forced labor camp in Buru. His incarceration there with Pramoedya, along with his role in getting the book published, led to a lifelong friendship with the celebrated writer.

Lukas was enjoying life as a private tutor when, sometime in the late 1990s, Pramoedya asked him to come to Jakarta and join his newly created organization, the Victims of the 1965/66 Murders Research Foundation (YPKP). He didn’t stay long after butting heads with other former political prisoners (“They prance around as if the Indonesian Communist Party was still a thing. It’s ridiculous!”), but he remained an outspoken presence in the movement to rehabilitate victims of the 1965 massacre.

In 2004, he was approached by Ribka Tjiptaning, the daughter of a massacre victim who became a prominent politician. She wanted to create a new nursing home for former political prisoners with the help of politician Taufik Kiemas and former Indonesian president Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid. However, she needed somebody, “a stickler for rules”, to help manage the place. The famously stubborn Lukas was a natural choice.

Panti Waluya Sejati became his pet project, and his devotion toward it afforded him a sense of purpose in his golden years. Despite being notably younger than its other residents, Lukas took on a leadership role. “I asked everyone to read as often as possible, so we have lots of stories to tell visitors,” Lukas recalled. “We survive because of their kindness. The least we can offer them is our wisdom.”