Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsGrim romance: Eka Kurniawan on ill-fated characters and writing what he knows

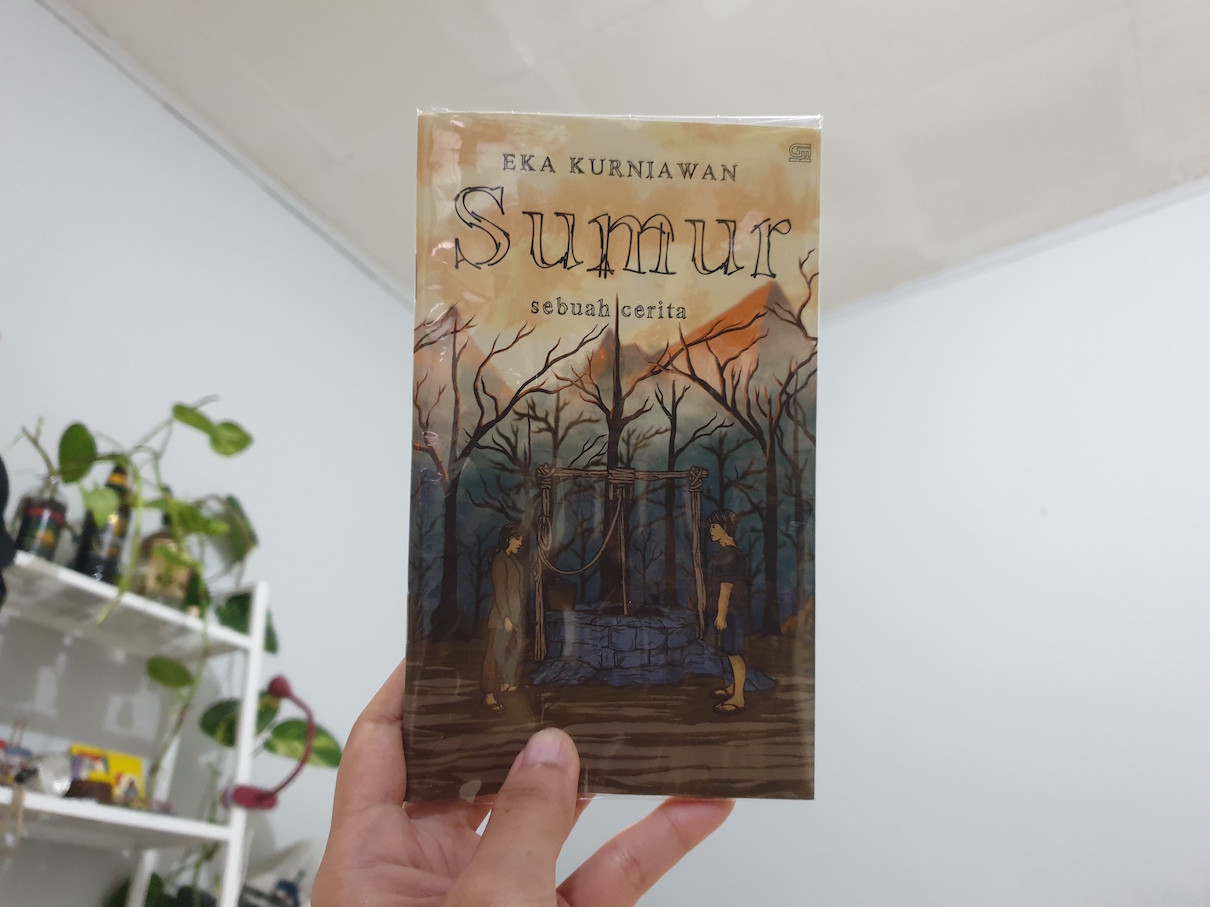

Writer Eka Kurniawan’s Sumur is a gripping novella filled with forbidding allegories about climate change and its effects on humanity’s relationship with itself and its surroundings.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

aving originally been written in Indonesian, Sumur was first published in September of 2020 in English as The Well, as a part of the Penguin Books’ anthology Tales of Two Planets. Its Indonesian version has now been released in Indonesia, via publisher PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

The novella is limited edition, with only 2000 copies printed. A bookmark accompanying the book states: “This book will only be printed once. One day it will be a rare item.”

The move is not simply marketing schtick, insists Eka, who said the aim was to present the book for “those who really want to read or have it.”

“It is not a gimmick, because we were not sure there would be many people willing to buy a thin book amid the pandemic, when book sales are at their lowest. So, well, we think it’s wise to announce that the book will only be printed once.”

The book ended up selling out and is no longer available on Gramedia’s official online stores.

A short story running 50 pages, Eka did not think it would find publication in any form.

“It was too long to be published in mass media, and it might be too long until it would be included in another anthology because I was not in the process of writing other short stories,” Eka told The Jakarta Post.

Eka gained public attention when the English version of his novel Lelaki Harimau (Tiger Man) was longlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize. In 2019, he received a Prince Claus Award in the literary category. His works have been translated into more than 30 languages.

Beyond borders: Eka Kurniawan’s books have been translated into 35 languages. (Courtesy of goodreads.com/-)Critical romance

Sumur delivers a heart-wrenching story of lovers Toyib and Siti, whose relationship is thwarted by a climate crisis and water conflicts, which have upset their village’s social fabric. Despite being a short read, the novella strikes a blow to sentimental hearts, leaving readers with an ache that lingers long after finishing the book.

Eka said he used the story to write about climate change in simple language. The writer avoided hard-to-understand jargon.

The author spent his childhood in the rural area of Tasikmalaya, West Java, and relied on first hand experiences to evoke the rural conflicts found in Sumur.

“I was raised in a family of farmers. Oftentimes I heard stories of similar disputes, usually horizontal conflicts between farmers, or between farmer groups, or between a farmer group and a powerful party who had the authority to control the water spring.”

Eka wrote the story in Ciputat, Tangerang, where he now resides. He did it in between writing another novel. Though the specifics of the process are clear to him, the inspiration is not.

“I forgot which incident inspired me to write that short story. Maybe I was a little bit nostalgic and was reminded of a special well, one at my mother’s house that was rarely dry,” Eka reminisced.

“At my village there were only two wells that never dried. The other one was located near a mosque. In the dry season, many of my neighbors had to take their water from there.”

Draft collection of tragic fates

Eka said he liked to immediately write drafts of stories whenever inspiration struck. He would then shelve them and take them out when the time was right.

"Stories are not written in one sitting. At first, I will only scribble a short draft. When I have time, I will add more elements, or I will change the plot. I never have a fixed story design,” Eka said when asked about his writing process. “I have many story drafts that will always be the subject of an overhaul.”

The author: Eka Kurniawan attends the launch of his book, 'O', in Jakarta on March 13, 2016. (The Jakarta Post/Wienda Parwitasari)“[It was] only when John Freeman [editor of Tales of Two Planets] contacted me to participate in the anthology, that I chose Sumur because the story fits the topic proposed,” Eka said.

“The only things I need to write stories are the [right] time and mood,” Eka said, laughing. The process takes anywhere from two or three days to months and years.

Eka said he had always relied heavily on things he already knew or ideas he had absorbed from films, books or people’s anecdotes. He then bends the ideas into something that interests him.

The protagonists of Sumur, Siti and Toyib, are just two of Eka’s substantial collection of ill-fated characters. His previous novels and short stories are full of unfortunate people with extraordinary life journeys. They typically end up dead, in prison or insane.

Eka said his characters, just like people in real life, did not have the power to control how the world around them unfolded.

“I don’t know what to say, sometimes it’s the plot that takes them there. It’s rare that I have any story design where the characters will end up like this or like that,” he said. “Every time I write, it is a new journey. The characters and their situations will help me reach their unfortunate ends.”

We are no longer accepting short story submissions for both online and print editions. New submissions to shortstory@thejakartapost.com will not be published.