Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDown syndrome: Beyond the classroom

Bake on Friday: Students, comprised of those with Down syndrome and other special needs, bake chocolate cakes in the Center of Hope in Sunter, North Jakarta

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

B

span class="caption" style="width: 398px;">Bake on Friday: Students, comprised of those with Down syndrome and other special needs, bake chocolate cakes in the Center of Hope in Sunter, North Jakarta. JP/Dina IndrasafitriNine-year-old Dimas was lying face down under the desks at which his classmates and teacher were studying last Monday.

A few minutes later, he got up and resumed his task of connecting the short lines his teacher, Iin, had drawn by hand earlier.

The lines made up the shapes of vowels and although Dimas’ “I”s are somewhat well-formed, his “U”s were mostly squiggly scrawls.

Although Dimas’ progress, who has Down Syndrome, might be seen as slight by some, his mother said that his learning and everyday skills have improved greatly since she enrolled him in the Zinnia Special School in Tebet, South Jakarta, two years ago.

Dimas is one of some 300,000 children in Indonesia born with Down syndrome, a genetic condition caused by the presence of all or a part of an extra 21st chromosome in one’s cells. The condition results in delays to one’s physical and mental development.

March 21 is commemorated as World Down Syndrome Day, in reference to the extra chromosome.

According to medicinenet.com, the syndrome gets its name from Doctor Langdon Down, who made several important observations about the syndrome in 1866.

Some parents are choosing to enroll their children with this condition into schools and other educational and training institutions to equip them at the very least with basic everyday skills, such as speaking and good hygiene.

“He wasn’t able to speak at all; now, he can say ‘mama’, ayah [father], and he can write a little bit, too,” Damira said.

Wagiman, one of the teachers at Zinnia, said that schooling actually makes a big difference in children with Down syndrome, as well as various other conditions that hinder childhood development.

In some cases, the school or institution is also seen as a way to keep those with Down syndrome active, as it is hard for them to find regular jobs.

Zinnia Foundation founder Imas Gunawan said that several students with learning difficulties in the school are already around 30 years of age, and in the past there have also been students of 40.

“Perhaps their parents thought it would be better for them [to remain in school] rather than staying at home,” she said.

There are other alternatives, however, besides formal schooling. The Indonesian Special Olympics (SOIna), for example, gives special-needs people a chance to excel in sports.

And excelled they have. Last year, Indonesian athletes at the Special Olympics won 15 gold medals, 13 silver medals and 11 bronze medals.

The Center of Hope in Sunter, North Jakarta, provides another alternative for those with Down syndrome, especially those who have finished primary or formal education.

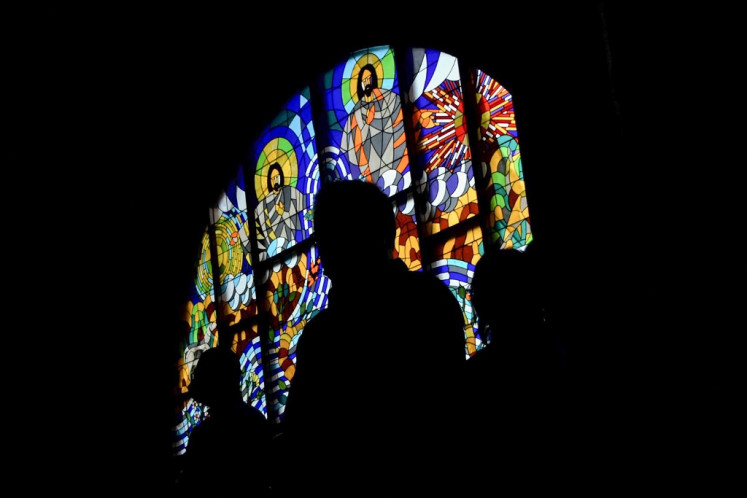

Eyes on you: A student in Center of Hope adjusts her spectacles during a lesson. JP/R. Berto Wedhatama Last Friday, in the center’s large, air-conditioned room, the students learned how to make juices, bake, use a computer, and dance.

Teacher Dewi Wardhani Suratika said the lessons taught at the center mostly revolve around practical skills and knowledge “All the lessons here are actually the application of the [lessons taught in regular] schools,” she said.

For example, the center conducts outings to supermarkets to teach students the concept of money.

The students, despite often being referred to as “kids”, are actually in their teens or even late 20s.

In a room adjacent to the main one, where the cooking utensils are, around four students were copying a text from a piece of paper using a computer.

Yona, one of the students, was typing visibly faster than the other three. She read softly — word by word — as she typed the text telling of France’s Eiffel Tower.

When she spoke, the sentences were in very formal Indonesian. “I usually go out of the house for Kumon [math course], swimming lessons, and the like,” she said when asked about her daily activities.

Dewi said that Yona’s learning ability is, on average, above that of her peers in the center.

The variety of learning abilities among people with Down syndrome can be due to a number of factors, including whether there are early interventions, such as speech and cognitive therapies.

Ayoh, the mother of 8-year-old Nasya, who has Down syndrome, said that therapy had been started early, when Nasya was only a few months’ old.

Her therapies included speech therapy, motor and occupational therapy, she said. Prices averaged around Rp 100,000 (US$10.9) per session, which were held once or twice a week.

According to Ayoh, Nasya’s motor skills are now quite developed and she is very active. She is capable of using chopsticks and is usually quite talkative.

Despite the differences among those with Down syndrome, there is one looming question of what will happen after school, the lessons and the gold medals?

And while, for some at least, the answer might be a lifetime of schooling and learning, there is also the question of what happens when there are no longer parents or other relatives who can provide financial support for the learning activities?

For some parents, like the father of Najri, who goes to Zinnia school with Dimas, the assurance that their children with Down syndrome can lead a life without having to rely too much on others would be enough.

Dancing queen: Students in Center of Hope in Sunter have their dancing lessons with a teacher from a school for special needs. JP/R. Berto Wedhatama “My hope [for Najri] is that he can be relatively independent. So that he can do everything by himself. Praise the Lord, now he can put on his clothes, take a bath and go to the toilet by himself,” he said.

Ayoh said that she hoped the government would pay more attention to the needs of children like Nasya.

“At least there should be a place for them to go to after education,” she said.

Ayoh added that she had been lucky enough to be able to afford the therapies and education fee. “What about the parents who can’t pay for those things?” she asked.

Even the institutions are facing challenges. Several parts of the Zinnia school building, for example, are visibly in need of repair, and at times teachers can feel overwhelmed with the task of handling students with different conditions. Dimas shares his class with two other students, both with learning difficulties not rooted in Down syndrome.

To tackle this, teacher Wagiman said he often resorted to a “middle way” that could be applied to a number of students, and he was also flexible in his teaching methods because, according to him, every child was different.

According to founder Imas, the school has been fairly lax in demanding payments, with some students’ parents paying the full fee of around Rp 350,000 a month, but others paying as little as Rp 50,000 and several students even attending for free.

She said that in the past, there had been numerous donations and volunteers helping the school with financial matters and offering new workshop ideas, but the help decreased after the monetary crisis in 1998. Imas’ increased age now prevents her from actively going out to seek assistance and ideas, although there are some additional funds from the government.

The Center of Hope charges a higher fee, but Dewi said that she is still looking for ways to cover additional costs, like the ingredients used for baking. She is also looking for a more “appropriate” place, with dedicated classrooms for each activity.

Despite the persisting problems the chairwoman of the Indonesian Down Syndrome Society, Aryanti R. Yacub, said there had been some progress, at least among the general public, regarding Down syndrome awareness.

“There is a gradual sense of acceptance from society. [People with Down syndrome] are now less afraid of seclusion or mockery,” she said.