Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIf only he’d been a little less ‘intimidating': In memoriam of Sabam Siagian

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

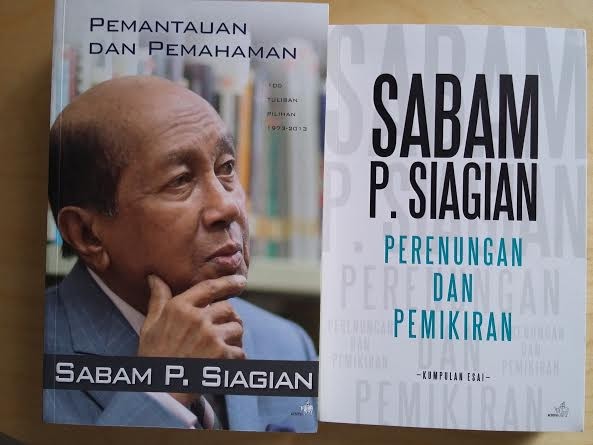

t was such a surprise to read that our senior editor Sabam Siagian (May 4, 1932 - June 3, 2016) mentioned the name Jahidi in the acknowledgement section of a book titled Sabam P. Siagian Perenungan dan Pemikiran (Sabam P. Siagian Contemplation and Thought).

I never expected Sabam, a high-profile journalist, diplomat, politician and public intellectual whose presence in The Jakarta Post newsroom was always both frightening and “intimidating”, would mention my friend Jahidi as an “office boy… [whom] from time to time contains my exasperation not caused by [him],” in his book.

The newsroom staff mostly hoped “SS” (referring to him by his initials), who regularly appeared in the office up until his last days, would not approach them at their desks, as he would usually pose questions and comment on even small things in an intimidating tone.

“Who are you?” was his only response when in 1996 I passed on to him regards from his close friend, noted church hymn and patriotic song composer Alfred Simanjuntak (1920-2014), a teacher of mine.

Since then, I was never willing to pass neither messages nor regards to our first chief editor.

“You’re better off asking me to write an essay than to pass your regards onto Pak Sabam,” I jokingly told University of Indonesia (UI) philosopher Rocky Gerung. We both laughed.

I couldn’t figure out whether he believed that his communication style could push us to become better journalists, but for sure he always set a high journalism standard.

“[…] the quality of a newspaper is mostly determined by small things, details[…] As chief editor [of the Post] I am forced to be firm [to make sure the quality], [that is] what you describe as grumpy,” Sabam told a team of Kompas journalists in an interview in 1991.

Thus, it of course gave me a sense of pride to learn that such a great journalist wanted to discuss with me the data in my weekly column “Save Old Batavia”, which appeared in the Post between 1999 and 2001.

“Pak Sabam is happy with what you are doing,” my mentor, late senior journalist Thayeb I. Sabil told me.

The work desk of the late Sabam Siagian at The Jakarta Post. (JP/Damar Harsanto)

The work desk of the late Sabam Siagian at The Jakarta Post. (JP/Damar Harsanto)

Years later, once again Sabam made me proud as an editor of a series of articles addressing various urban issues, criticizing Jakarta as an unfriendly city for the marginalized; elaborating on the effects of gentrification; describing the mushrooming of gated communities and ways to narrow the social gap with the surrounding areas; showing successful private sector initiatives in kampung development or on the informal sector as well as on the concept of “social [shopping] malls”.

“We need to produce these kinds of pieces more often,” Sabam was quoted as saying.

He never showed his appreciation directly to me, and vice versa. I had the privilege of listening to his sharp comments, insights and visions on various issues, be it geopolitics, national politics and economy as well as urban problems and even popular culture, when he was present at editorial meetings.

In my opinion, his “intimidating” persona hindered the Post’s younger generation from tapping the knowledge, skills and various other talents the late resourceful journalist had, despite him being around the newsroom.

It was both an honor and surprise for me when in 2012 the senior editor met my invitation to attend the Pangumbaran Ing Bang Wetan. The Dutch Reformed Church in Late Eighteenth Century Java: an Eastern Adventure book discussion. The author of the book was church historian Yusak Soleiman, my husband, who happened to be baptized by Rev. Isaac Siagian at GKI Kwitang Church in Kwitang, Central Jakarta, in 1967.

As a son of Dominee Siagian, Sabam was likely familiar with church history. He enthusiastically suggested that the audience delve into the contribution of the Gereformeerde Kerk, one of the denominations of the Dutch Reformed Church, in Indonesia.

The church, with its noted theologian-cum-church minister J. Verkuyl –who worked at the GKI Kwitang, was known for supporting Indonesian independence from Dutch colonialism before and after the 1945 proclamation of independence.

Sabam’s formative years were mainly shaped by Protestant education institutions. His father was a figure behind the existence of the famous Perkumpulan Sekolah Kristen Djakarta (the Association of Jakarta Christian Schools) (PSKD), which was the legacy of the Gereformeerde Kerk.

Later on, he was active in the Indonesian Christian Student Movement (GMKI) while studying at UI’s School of Law, and served as the movement’s chairman between 1957 and 1959. He never finished his undergraduate studies.

Sabam studied several disciplines at several universities and was active in journalism and in diplomatic affairs while he resided in the US for 14 years, where he married in 1962 Stella Maris, with whom he had two sons.

Upon returning to Indonesia, he was pushed by his father and noted statesman Gen.TB Simatupang into journalism. In 1973 he started his career at Sinar Harapan afternoon daily, which later on was dissolved by the authoritarian New Order government under President Soeharto in 1986 and finally transformed into Suara Pembaruan.

He was assigned to lead The Jakarta Post as chief editor when it was established in 1983, a position he held until 1991, and became senior editor upon completing his tenure as the Indonesian ambassador to Australia (1991-1995).

Sabam also ever served as a People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) member between 1999 and 2005 as a representative of the Indonesian Union of Christian Intellectuals (PIKI).

Despite being a Christian political figure, he never showed his Christian identity while he in the Post’s newsroom.

I never knew that he resorted to prayer when facing situations too difficult to handle. “Pak Sabam ever served us lunch and prayed for us when we, by accident, met him at Suara Pembaruan in 2013,” said Bona Sigalingging, a fighter for the rights of the years-long beleaguered GKI Yasmin congregation, whose house of worship in Bogor, West Java, was locked down by the Bogor administration despite the building’s legality.

At that time, Pembaruan leaders were not that sympathetic toward GKI Yasmin’s struggle, according to Bona. “But Pak Sabam invited us to pray for [God’s] protection and strength for our struggle.

“Because [GKI Yasmin’s] struggle is not aimed for their own sake, but for that of our nation; so that justice, the Constitution and plurality of our country are maintained,” Bona quoted Sabam’s prayer that was deemed heartening for the congregation, which holds a Sunday service in front of the Presidential Palace in Jakarta every two weeks.

“Try to get to know Oom [uncle] Sabam better,” prominent children choir activist Aida Swenson once suggested to me, “and you will find he is actually a nice guy,” the daughter of Alfred Simanjuntak added.

Sabam Siagian, journalist par excellence, as the Post's current editor-in-chief Endy M. Bayuni regarded him, passed away in Jakarta on June 3 due to extended health complications, including diabetes. He will be buried on Sunday at Menteng Pulo Cemetery in South Jakarta.