Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

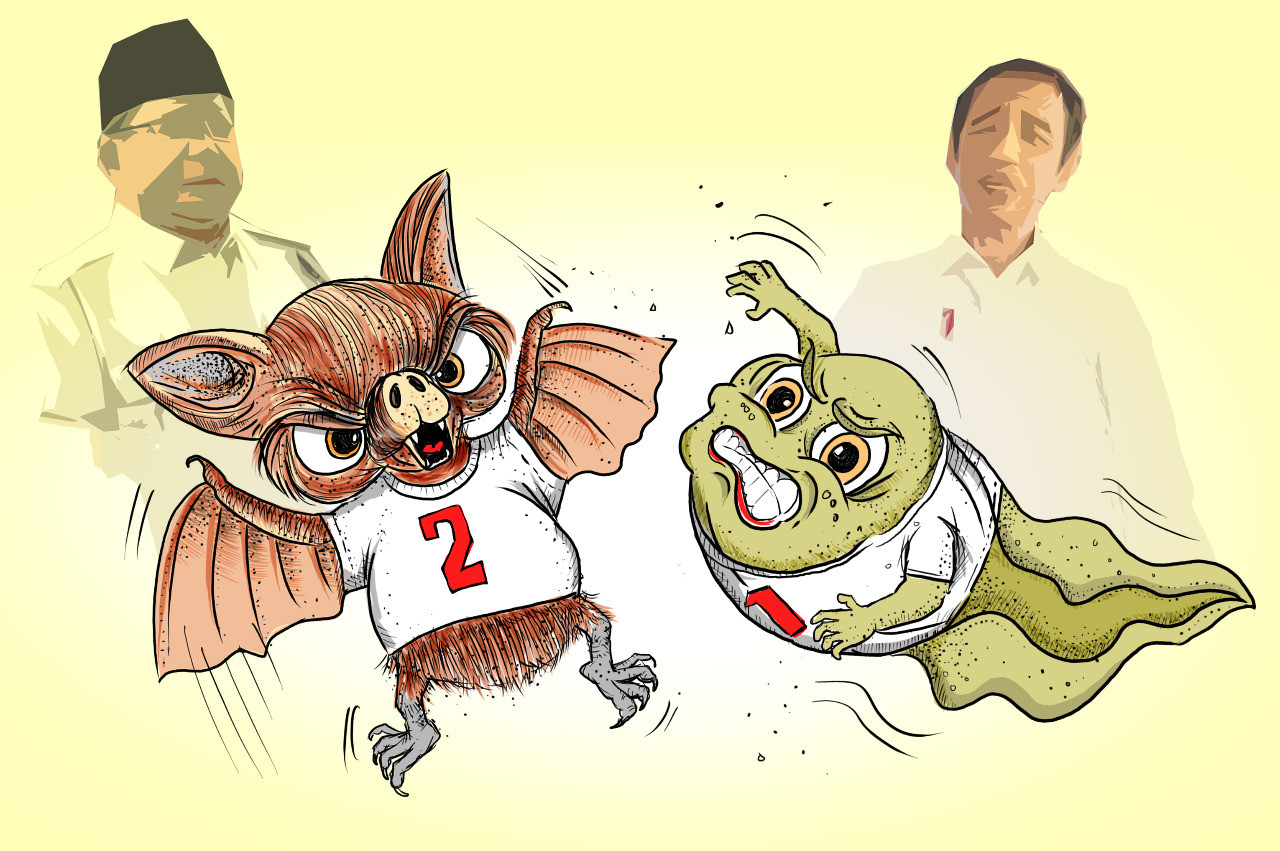

View all search resultsOf tadpoles and small bats: How name calling deepens Indonesia's great political divide

What do the larval stage of a frog and a winged mammal have to do with politics?

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Civility is not always the norm in political discussions.

Case in point is the increasingly rampant use of slurs used by Indonesian social media users to insult those who do not share their political views.

The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) recently asked people to refrain from using the words cebong (short for kecebong or tadpole) and kampret (small bat) to describe supporters of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and Prabowo Subianto, respectively.

“The use of these terms should not be used because it violates ahlakul karimah [manner],” said the MUI’s head of international relations division, Muhyidin Junaidi, on Monday as reported by kompas.com. The terms, he added, were especially inappropriate in public spaces, including majelis taklim (religious congregation).

Muhyidin said calling people with opposing political views names was needless and might tear the nation apart.

But since when did the words cebong and kampret become political? What do the larval stage of a frog and a winged mammal have to do with politics?

The two words became popular shortly after the 2014 presidential election, arguably the most polarizing one in the country’s history. It is safe to say that the popularity of the two words was triggered by and, at the same time, further deepened political polarization in the country.

Jokowi’s tadpoles

The word cebong is used by Prabowo supporters to insult Jokowi’s supporters simply because the latter is known to keep frogs in the ponds of the Presidential Palace in Bogor, a habit which dates back to his days as mayor of Surakarta, East Java.

In an episode of popular talk show Mata Najwa, his youngest son, Kaesang Pangarep, revealed that Jokowi took tadpoles from the ponds and released them when they turned into frogs. The episode aired on Feb. 24, 2016. Since then, Kaesang often uses the word cebong as a joke.

The term cebong was later used to attack supporters of Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama ahead the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election. Ahok, who now goes by BTP, was a close ally of Jokowi. At that time, Ahok was in a race against Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono and now-Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan.

Anies was backed by Gerindra, Prabowo’s party.

One common phrase uttered during this period is Cebong mana paham? (A tadpole would not understand) -- implying that Jokowi’s supporters was of low intelligence. Opposition figure Rocky Gerung famously said all cebong in a pond had a collective IQ of 200.

Bila anda dibully oleh gerombolan beringas ber-IQ 200 (digabung satu kolam), tertawalah sekeras-kerasnya. Itulah cara menghormati badut:)

— Rocky Gerung (@rockygerung) August 27, 2017

But the word seems to have gained traction after National Mandate Party (PAN) patron Amien Rais used the words in his political speeches.

Kampret

The origin of how kampret entered the political discourse is vague.

Kampret is often been used as a common curse word, mostly in Java because the word in itself means small bats in Javanese. Bat in Indonesian is kelelawar, not kampret.

Writer and avid social media user Denny Siregar wrote in his blog that he once asked his friend the reason why kampret was used to refer to Prabowo’s supporters. His friend answered that it was because bats slept in an upside-down position, much like the logic of Prabowo’s supporters.

According to novelist Okky Madasari, kampret is a “derogatory twist on KMP”. In 2014, Prabowo’s coalition was named Koalisi Merah Putih (Red and White Coalition).

Other than the MUI, many other parties have called for an end to the use of such slurs as cebong and kampret in political discussions. But with election day fast approaching, the calls have largely fallen on deaf ears.