Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsCop-out on climate finance at COP29

It seems that saving the planet from an impending climate catastrophe does not figure in the priorities of developed countries.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

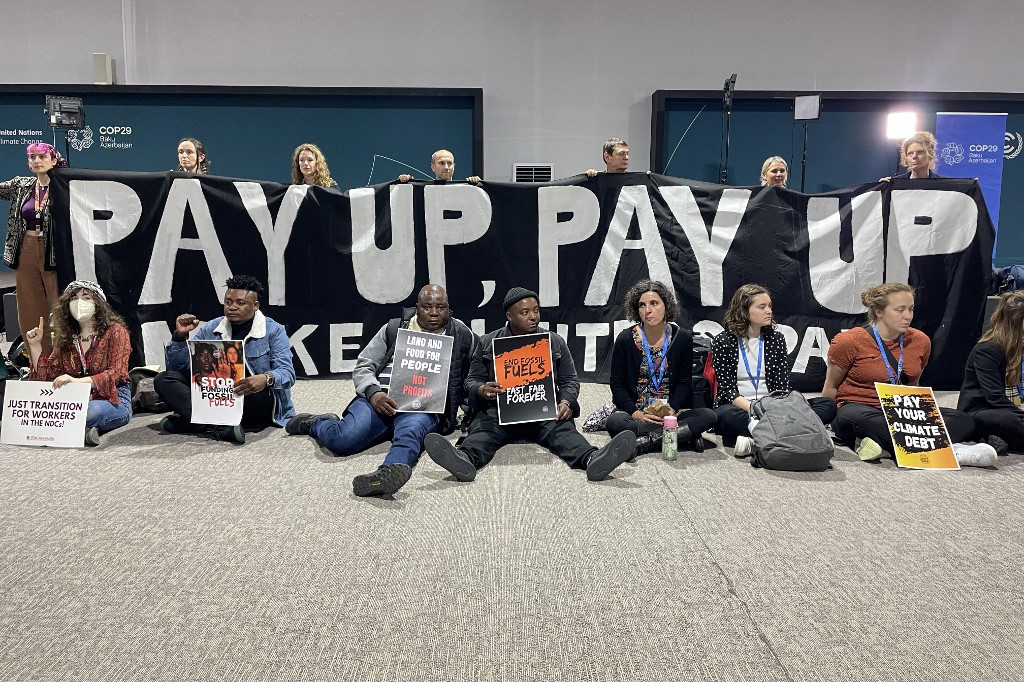

he decisions taken at the recently concluded Conference of Parties (COP29) of the Climate Convention in Baku once again show that adequate climate finance will continue to remain elusive.

COP29 agreed to triple finance to developing countries, for “protecting lives and livelihoods”. The developed countries agreed to make available at least US$300 billion per year by 2035 for developing country parties for climate action.

This is thrice the previous goal of $100 billion annually by 2020, agreed to in the Copenhagen Accord in 2009.

Additionally, COP29 called “on all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing country parties for climate action from all public and private sources to at least $1.3 trillion per year by 2035”.

These two decisions formed the basis of the “new collective quantified goal” on climate finance.

It is ironic, however, that these decisions at COP29 made headlines even as the financial pledges to developing countries faced two sets of problems.

First, the previous target of $100 billion that was to be achieved by 2020, was met after a two-year lag.

Bilateral agencies and funds from multilateral development banks in the developed countries provided $91.6 billion. The developed country governments provided only $21.6 million.

Developing countries, therefore, relied on private sources of finance with stiff borrowing conditions, a tall ask for the debt-burdened low-income countries.

Second, the quantum of funding promised in Baku fell considerably short of the needs of the developing countries.

Several estimates suggest that the developing countries would currently need at least a trillion US dollars annually to combat climate change and its impacts.

In its submission, India had argued that the “developed countries need to provide at least $1 trillion per year, composed primarily of grants and concessional finance” and that the “quantum can be scaled up in proportion to the rise in the needs of developing countries”.

In the same vein, Saudi Arabia argued that the developed countries should provide $1.1 trillion to developing countries, which must largely be grant-based and concessional finance.

Assessments from several institutions, including the Convention’s Standing Committee on Finance (SCF), have endorsed these estimates.

The SCF estimated earlier this year that the financial requirements of 93 developing countries, based on the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) needed to fulfill their Paris Agreement commitments, would range from $5 trillion to $7 trillion until 2030.

Based on a similar approach, another set of estimates showed that the aggregate financing needs of 126 developing countries is likely to be $7.8 trillion to $13.6 trillion until 2030.

However, both reports acknowledged that the estimates could be too low considering that not all NDCs of the developing countries were analyzed. Also, the national climate action plans may not necessarily represent the maximum achievable national objectives to meet the collective climate goals.

The UN trade and development agency, UNCTAD, estimated that the annual requirements of the developing countries would increase from $500 billion in 2025 to $1.55 trillion by 2030.

Financing, according to UNCTAD, should be primarily achieved through a grant-equivalent core goal for bilateral contributions from the developed countries. It has suggested starting at 0.7 percent of the Gross National Income (GNI) from 2025, going up to at least one percent by 2030.

UNCTAD’s target seems to be an ambitious one given that most developed countries have never met the UN target set in 1970 of spending 0.7 percent of their GNI on official development assistance. .

The Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance estimated that emerging markets and developing countries, excluding China, need to invest and spend close to $2.4 trillion a year by 2030 to meet the climate goals.

Excessive attention given to the “new collective quantified goal” at Baku also took the focus away from the other key financial mechanism, the “Loss and Damage Fund (L&D Fund)”.

This long-delayed mechanism for supporting the most vulnerable and adversely affected countries by climate change was operationalized during COP29.

The importance of the L&D Fund has increased significantly over the past few years in view of the catastrophic climate events affecting several developing countries.

Since its launch in 2023, the pledges to the L&D Fund from 26 countries have totalled $749.3 million. By the end of 2024, less than a fifth of the total pledges could materialize, with the US contributing just 13.6 percent.

As in the case of the “new collective quantified goal”, financial resources would be a major constraint for the effective operation of the L&D Fund.

Available estimates indicate that the actual requirements were between $171 billion and $671 billion in 2020. They are expected to increase to between $447 billion and $894 billion by 2030.

The inadequacy of the L&D Fund clearly stands exposed.

When they endorsed the Climate Convention, the developed countries had made a commitment to “provide new and additional financial resources to meet the agreed full costs incurred” by developing countries “in complying with their obligations”.

They recommitted themselves in the Paris Agreement, agreeing to assist developing countries “with respect to both mitigation and adaptation in continuation of their existing obligations under the Convention”.

Through the three decades of the implementation of the Climate Convention, developing countries had consistently argued that the developed countries never intended to provide them with the climate finance necessary.

It would seem that saving the planet from an impending climate catastrophe does not figure in the priorities of the developed countries.

Defense spending, for example, is one of the highest priorities in the US, which, in 2024, was close to $2 trillion, or over 16 percent of the federal budget.

Over the past two years, US defense spending increased by 16 percent, fuelled by support to Ukraine and Israel.

The US has provided over $25 billion to Ukraine and $17.6 billion to Israel in the past two years. By contrast, the US has contributed just $17.6 million to the L&D Fund.

---

The writer is a distinguished professor at Council for Social Development in New Delhi, and was a professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning in Jawaharlal Nehru University. The article is republished under Creative Commons license.