Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsSoutheast Asia, world need UN special rapporteur on democracy

Democratic progress in Southeast Asia remains stifled by authoritarian resilience, weak institutions, and the misuse of legal frameworks to silence opposition.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A giant puppet depiction of Pinocchio is pulled by participants during a demonstration organized by various humanitarian and environmental organisations and students in Jakarta on Feb. 7, 2024, calling for democracy, human rights and climate change ahead of the 2024 presidential election. (AFP/Yasuyoshi Chiba)

A giant puppet depiction of Pinocchio is pulled by participants during a demonstration organized by various humanitarian and environmental organisations and students in Jakarta on Feb. 7, 2024, calling for democracy, human rights and climate change ahead of the 2024 presidential election. (AFP/Yasuyoshi Chiba)

T

he world is experiencing a democratic recession. For nearly two decades, more countries have shifted toward authoritarianism than toward democracy. Fundamental freedoms are eroding, digital authoritarianism is expanding and civic space is shrinking.

Yet, despite proclamations of support for democracy, many governments worldwide have failed to halt this decline and, in many cases, have unwittingly contributed to it.

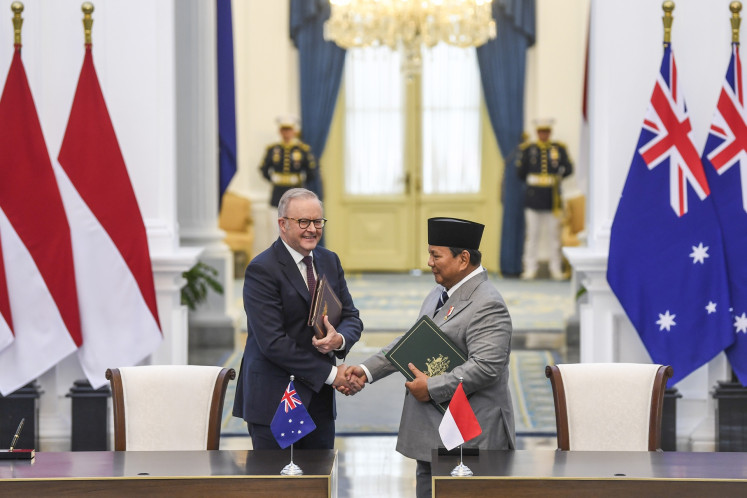

This crisis is not just about failed interventions but also about the contradictions in how democracies engage with authoritarian regimes. Governments that claim to champion democracy continue to sign trade deals, security pacts and investment agreements with repressive states, reinforcing their grip on power.

Diplomatic priorities often place stability and economic interests above governance and human rights, leaving democracy promotion as an afterthought, or worse, an inconvenience.

The lack of a dedicated global mechanism to monitor democracy further deepens these challenges. While human rights benefit from extensive United Nations oversight through multiple special rapporteurs, democracy, a core UN principle, has no such mechanism.

Recognizing this gap, discussions on the establishment of a UN special rapporteur on democracy have taken place at major international forums, including the Summit for Democracy in March 2024 and the Community of Democracies in June 2024.

Democracy underpins human rights, sustainable development and global peace. It provides an environment where people can freely participate in decisions that shape their lives, hold governments accountable and enjoy equal rights and freedoms.

Yet, when the UN Charter was drafted in 1945, democracy was not explicitly mentioned, many founding member states were not democracies themselves. Still, the opening words, “We the Peoples”, embody the fundamental democratic principle that legitimacy derives from the will of the people.

The UN has long supported democratic governance, assisting in electoral processes, strengthening civil society and fostering constitutional reforms in post-conflict states. But without a dedicated mechanism to monitor and promote democracy, these efforts remain fragmented and miss the big picture.

A UN special rapporteur on democracy would bridge this gap by providing regular assessments of global democratic trends, identifying threats and opportunities, and engaging with governments, regional organizations and civil society to strengthen democratic resilience.

Democratic progress in Southeast Asia remains stifled by authoritarian resilience, weak institutions, and the misuse of legal frameworks to silence opposition.

In Myanmar, the military junta continues its brutal suppression of pro-democracy activists, ethnic groups and opposition leaders. Cambodia’s recent elections once again exposed how autocratic rulers manipulate democratic processes, using repression to eliminate opposition.

Thailand’s 2023 general elections highlighted the limits of electoral democracy, as the military-backed Senate blocked the Move Forward Party from forming a government despite its decisive victory. In Indonesia, concerns are growing over oligarchic influence, a weakening of the rule of law and the erosion of checks and balances.

The Philippines faces persistent online disinformation campaigns and state-led harassment of journalists and activists. Meanwhile, in Vietnam and Laos, where one-party rule remains firmly in place, political repression is routine, with dissidents and independent media facing severe crackdowns.

Democratic backsliding in the region is further intensified by digital authoritarianism. Governments increasingly use surveillance, censorship and restrictive cyber laws to monitor dissent, silence critics, and control information. Laws on fake news, data privacy and online defamation are widely misused to suppress free speech, posing serious threats to digital rights and press freedom.

ASEAN's commitment to democracy is largely rhetorical, with no institutional framework or binding commitments to uphold it. Its consensus-driven decision-making process has proven ineffective in addressing political crises, as seen in its lack of meaningful action on Myanmar. Instead, the ASEAN way has shielded authoritarian leaders, allowing them to evade regional accountability while maintaining repressive rule.

A UN special rapporteur on democracy could fill this gap.

The rapporteur could provide impartial reports, recommendations and a global platform to address democratic erosion in the region. According to discussions thus far, the mandate in particular could investigate the integrity and independence of electoral management bodies, whether there is an environment for free and fair elections, and key institutional components required for robust democratic governance such as separation of powers and effective parliamentary oversight.

The special rapporteur on democracy, supported by a group of expert advisors, could make a tangible impact on Southeast Asia by helping strengthen ASEAN’s democratic commitments, embedding democratic principles within its frameworks and dialogues, and providing insights on improving governance and electoral processes.

The mandate could work with the existing forums in the region such as the Bali Democracy Forum (BDF), which was initiated by Indonesia in 2008. The BDF has organized 18 annual forums since 2018.

The mandate could engage directly with ASEAN to push for stronger regional commitments to democratic principles and support civil society organizations advocating for democratic reforms.

The mandate could also empower civil society organizations and pro-democracy parliamentarians by supporting their advocacy efforts, ensuring sustained international engagement, facilitating high-level discussions on democratic reforms and serving as a platform for regional cooperation on democracy-building efforts.

However, establishing this mandate may encounter resistance, particularly from some Southeast Asian governments that perceive it as a challenge to sovereignty or a Western-driven agenda.

In reality, many non-Western countries are now among the most active proponents of democratic rhetoric at the UN, while nations like the United States have scaled back their engagement. Regardless, the political, cultural and historical diversity across regions underscores the need for context-specific approaches to democracy promotion.

Despite these opportunities and challenges, the case for a UN special rapporteur on democracy is clear. Democracy cannot be left to decline unchecked. International engagement with authoritarian regimes cannot continue without scrutiny. The world cannot afford another decade of democratic decline.

For Southeast Asia, where democratic backsliding is a daily reality, having an independent UN mechanism to monitor and report on these threats is not just a symbolic step, it is an urgent, essential and necessary intervention.

***

Yuyun Wahyuningrum is executive director of ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR). Andreas Bummel is executive director of Democracy Without Borders.