Why we should not prohibit refugees from working

Even though the majority of refugees have lived in Indonesia for more than six years, they are still not fully entitled to basic human rights by the Indonesian government, including access to work.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

picture of chicken biryani, cooked and sold online by a female refugee living in Pekanbaru, that I shared on my social media account to attract more customers sparked an argument with a colleague at an immigration detention center, the government agency tasked with the control and surveillance of refugees and their activities.

My colleague commented, “Refugees cannot engage in income-generating activities,” and then added, “To my knowledge, there is a regulation that forbids refugees from working.”

Her comments have raised doubts in my mind. While there is a regulation that prohibits employment for refugees in Indonesia, the legitimacy of this regulation is questionable and should be reevaluated.

The economic rights of refugees are protected under the 1951 Refugee Convention of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Articles 17-19 of the convention stipulate that signatory countries should permit refugees “the right to engage in” wage-earning employment, self-employment, and liberal professions with “as favorable as possible treatment” or treatment “not less favorable than” other noncitizens in the same circumstances.

Since Indonesia is not a signatory to the convention, however, it is under no obligation to follow the stipulations contained in the 1951 convention in overseeing the almost 14,000 refugees and asylum seekers in its territory.

Even though the majority of refugees have lived in Indonesia for more than six years, they are still not fully entitled to basic human rights by the Indonesian government, including access to work.

The prohibition on refugee employment was first stated specifically in Immigration Director-General Regulation No. IMI.1489.UM.08.05/2010 on the handling of illegal migrants. The regulation was subsequently replaced with Immigration Director-General Regulation No. IMI-0352.GR.02.07/2016 on the handling of illegal migrants desiring asylum or refugee status, which was signed April 19, 2016.

A statement to refugees attached to the regulation states: “Refugees must obey the regulations in Indonesia, which include a prohibition from working or engaging income-generating activities.”

However, if we refer to the hierarchy of Indonesia’s legislative framework, it can be inferred that this regulation is not legally binding. It contains principles that govern a code of conduct for refugees in Indonesia that includes a prohibition against driving without a license, hosting overnight guests in their accommodations, and being present at airports without supervision. The code of conduct also includes points on maintaining public order and reporting monthly to local immigration offices.

These are guidelines and are not very strict in nature. Additionally, since they are not enforced by law, noncompliance with any of the aforementioned instructions has few negative consequences in practice.

Authorities frequently seek to enforce the prohibition on refugee employment under Immigration Law No. 6/2011. However, it is incorrect to apply this law to refugees. The immigration legislation is clear: the migrant groups the law refers to are victims of people trafficking and smuggling. The law makes no explicit mention of “refugees and asylum seekers”, let alone specific issues regarding their protection.

The first legally binding piece of legislation regarding the oversight of refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia is Presidential Regulation No. 125/2016, under which Indonesia no longer labels refugees as “illegal immigrants”, but uses the definition of “refugee” given in the 1951 Refugee Convention.

While the presidential regulation provides a legal basis for uniform procedures such as rescue, shelter, registration, security and surveillance of refugees and asylum seekers, which are assigned to several mandated national and local state agencies, it is still poorly targeted and inadequate.

The regulation contains no provision on protecting the rights of refugees. It only governs refugees in the care of immigration detention centers, whose basic support is provided by the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In other words, the refugee communities that have formed organically in many urban areas are excluded from the presidential regulation.

Refugee communities in Indonesia rely heavily on limited financial assistance from international organizations for their survival and wellbeing. The IOM, for example, currently provides a monthly cash allowance of Rp 1.25 million (US$88) for food and medical expenses to around 7,800 refugees in the 85 IOM-run community housing complexes across Indonesia.

Meanwhile, UNHCR Indonesia is only able to offer financial support to a few hundred of the most vulnerable refugees living independently in and around Jakarta, and the support it offers is considerably lower than the amount refugees receive from the IOM.

The other refugees are left with few options. While some survive on external sources of income such as savings, loans or money from family members or friends back home or overseas, others are compelled to work in secret, despite the employment prohibition.

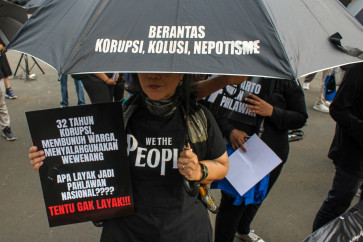

These refugees and asylum seekers engage in a variety of income-generating activities. They teach English and Arabic, open Middle Eastern restaurants, make cameo appearances in Indonesian soaps and TV commercials, and work as tailors, models, barbers and construction workers. Some resort to negative coping behavior to survive, such as prostitution. And all of them are working outside the protection of the law.

The Indonesian government should formally recognize this problem and introduce a new domestic refugee-specific law in harmony with the 1945 Constitution, and which recognizes the right to seek asylum and complements Presidential Regulation No. 125/2016. This new law would formalize the mechanism for managing refugees and asylum seekers found at sea and incorporate human rights protections.

Before this can occur, the government’s mindset must shift from viewing refugees merely as recipients of humanitarian assistance to recognizing them as ordinary people like you and me, and as such, equally deserving of basic human rights.

***

The writer is an immigration officer who worked with refugees and asylum seekers from 2014-2017; Australia Awards Scholarship recipient for Master in Public Administration (Management), Flinders University, Adelaide. The views expressed are his own.