Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBreaking the vicious cycle of a toxic work environment

A toxic work environment can leave negative effects on the mental and physical health of survivors. While it is yet to become a hotbed issue in Indonesia, some people are beginning to share their experiences in the hope of breaking the cycle.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

illions of Indonesian job seekers are struggling under the continuing uncertainties of the global pandemic, especially young workers.

I am one of them: a 22-year-old living from paycheck to paycheck.

Read also: Urgent need to tackle youth unemployment in COVID-19 pandemic

But in early January, I found an opportunity for a job as a writer. As I sat in front of my laptop before the virtual interview, I took a deep breath to calm my nerves.

“Hi, I’m sorry I’m late,” my interviewer said with a smile, which immediately put me at ease.

They had asked me to bring along an article I found lacking to discuss how it could be improved. I picked one that was published by my former employer, an education nonprofit organization, that I felt was weakly written and ripe for criticism.

But I hadn’t thought things through, and as I started talking about the article, something strange happened.

I struggled to find the words to explain what was wrong with the article, spiraling into panic and stuttering. Eventually, I fell silent. What happened?

Surviving a culture of abuse

I’d always wanted to write, and thought I could learn from my colleagues at my former workplace. But I didn’t write a single article in the two years I was there. My confidence deteriorated and my ability to write vanished. I tried. I worked on several drafts, leaving them unfinished. I was preoccupied with fear of humiliation that would come if I delivered less than a perfect piece.

Harsh critiques, belittlement, verbal abuse and being the target of humiliating jokes were common, and even a deep-rooted part of the organization’s culture. These were all claimed to be “objective-constructive criticism” and “harmless internal jokes”.

In the beginning, the “honest criticism” seemed beneficial. But they gradually turned into unsolicited criticisms that became jokes and then developed into mercilessly repeated insults.

Many others in the organization also had unpleasant experiences. I grew convinced that I had to get out of there for the sake of my sanity.

Prevalent and identifiable

Leaving that toxic work environment didn’t mean the end to its effects. I had internalized the toxicity and it deeply harmed my self-esteem. The tight job market as a result of the pandemic didn’t help, either. It made me shudder with anxiety to realize that the damage it had done might jeopardize my professional future.

I am by no means alone in surviving a toxic work environment.

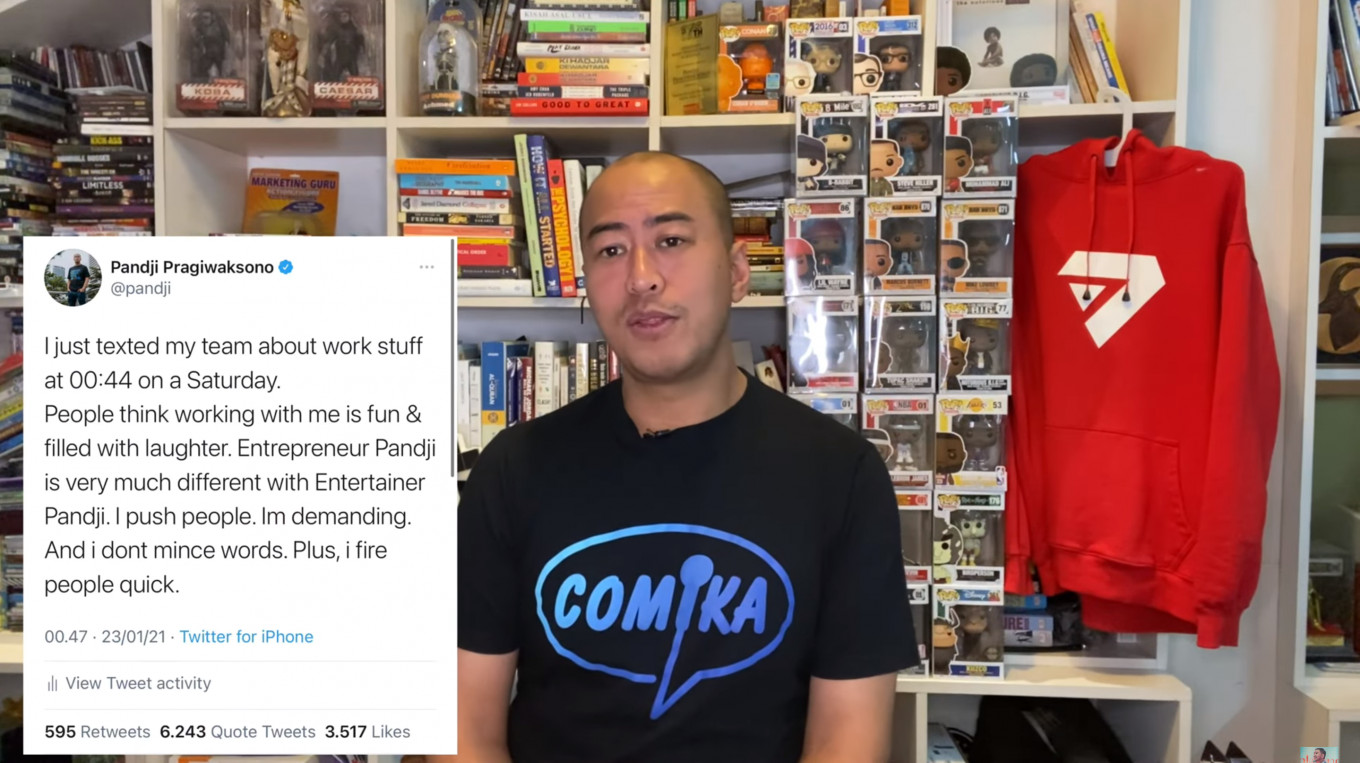

One indication of this can be seen in the uproar that followed a recent tweet from popular comedian Pandji Pragiwaksono (@pandji) on his “entrepreneurial side”, declaring how tough he was on his employees and that he often messaged them after midnight. Twitter users responded by calling him out as an “exploitative boss”.

The uproar prompted Pandji to post a YouTube video defending his midnight messaging because he is "unable to stop thinking about (his) company", referring to Comika, a "comedy content generator".

Pandji’s tweet wouldn’t have caused such commotion if this wasn’t such a prevalent and identifiable problem. A toxic boss is undoubtedly a key factor that contributes to a toxic work environment, as an asymmetrical superior-subordinate relationship often leaves workers powerless against an abusive boss.

Arsa (not her real name) is also a survivor of a toxic work environment. As a social media specialist at a Jakarta-based start-up, her managing editor constantly bullied her, often in a nonprofessional setting.

“She would find ways to blame me every day, ever since my first week,” the 30-year-old recounted, tearing up. “She ultimately blamed it on my ‘manner and attitude’. But I never [understood] what I did wrong.”

It wasn’t just the bullying. Arsa was also excluded from her division, because most of her coworkers were “tight” with the managing editor.

“I felt like it was partly because I was new to their ‘gang’,” she said, and one colleague who shared her concerns and sat close to Arsa ended up being moved elsewhere.

Arsa also experienced anxiety attacks that didn’t have obvious triggers.

“I had an anxiety attack at a cafeteria once. I was just eating my lunch as usual, it was normal. But suddenly it was so hard to breathe, I was choking.”

Seno (not his real name), 33, was once a mechanic at a bus company in East Jakarta. Despite having the skills and a matching vocational educational background, he only lasted six months.

“I enjoyed the first four months, but then our working condition only got gradually worse,” he told The Jakarta Post.

Seno and the other workers were paid below the minimum wage, and they survived on the tips they received for repairing buses. When their foreman tried to take the tips for himself, Seno spoke up. He was then subject to intimidation and moved to a more hazardous role. The intimidation continued to escalate until clashes broke out between the mechanics and bus drivers. So he quit.

Fight or flight?

For people like Arsa, Seno and me, the lingering effects of our toxic work environments still haunt us.

Dr. Jiemi Ardian, a psychiatrist, said that a “toxic work environment will activate the fight-or- flight [defense] mechanism”.

“In a repeating pattern, this unpredictable threat will also activate an unpredictable fight or flight defense mechanism that could surface at any time,” he said.

“In a new workplace, [unresolved trauma] may emerge as an old pattern, such as fear, insecurity, disrupted concentration, [and] impaired communication caused by the previous toxic work environment. These can influence performance and interaction in the new environment,” Jiemi added.

That’s not all. A toxic work environment can also have measurable, physiological impacts.

“The level of stress hormones in our blood spikes, and if it does so continuously without any [treatment] to lower the surge in the long term, it may cause chronic stress, in which the body adjusts to a new ‘balance’ where the body is tense instead of relaxed,” said Jiemi.

He added that chronic stress could increase the risk of heart disease.

Combined with the additional burden of accessing healthcare services, which might not be possible in the current health emergency, these impacts may deteriorate into a cycle of untreated health problems. This vicious cycle can often lead to an individual turning to pseudoscientific “quick fixes” and treatments, or resigning from the job altogether.

On the other hand, employees cannot afford to wait for an organization to reform even as it keeps perpetuating a debilitating cycle of trauma and health problems, particularly as the already tight job market continues to be exacerbated by the economic impacts of the pandemic.

Jiemi also noted that a toxic work environment was a structural issue that required organizational solutions.

“Individual solutions might be good in a certain context, but it doesn’t solve the problem. The problem does not only revolve around the [workplace] culture, but it is also systemic: policy regulations and mechanisms,” he said. “This is not an individual problem, this is systemic. What needs to change is the system, not the individual.”

In this regard, Jiemi suggested that unionizing might be one solution, as employees would have greater bargaining power as a larger group.

Workers often find their only solution is to unionize to battle unfair work practices. (Antara/Yulius Satria Wijaya)Unionizing for change

Seno now works at a factory. The working condition was also terrible at first, with no proper standards or factory layout.

But factory workers can form a union relatively easily, unlike office workers, and Seno suggests that the culture of white-collar work tended to pit employees against each other.

Four years after he joined the factory, Seno and his coworkers pushed for radical change of the company union. It is now an independent labor union able to protect its workers, providing safety nets and assistance.

“There are cases where workers are severely affected that they couldn’t bring themselves to come to work, and we managed to help them the best we could. [Employee wellbeing] is no longer a personal matter,” said Seno.