Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDoes Southeast Asia’s nuclear energy plan consider risks?

Some studies argue that the way of thinking and practices on risk management in energy sectors in Southeast Asia remain relatively low.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

N

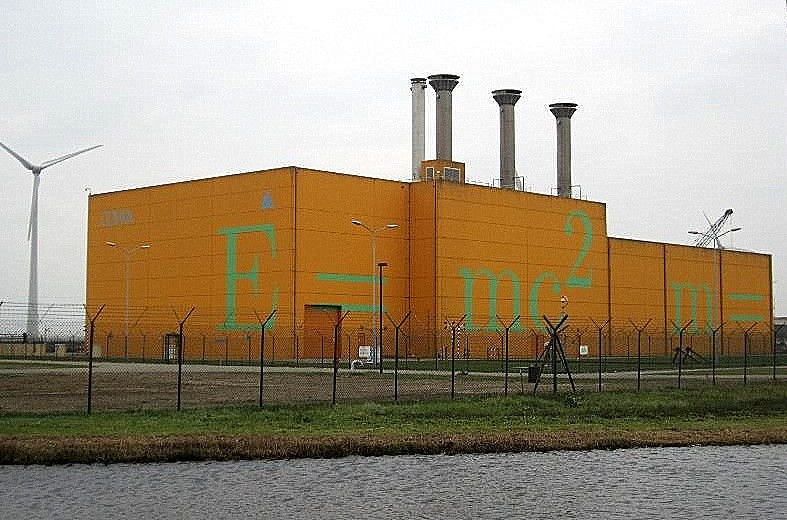

uclear energy has the potential to be part of the energy mix plan in the post-pandemic era in Southeast Asia. To complete the plan, the problem of radioactive (or nuclear) waste must be anticipated. It is an important component in managing risks from nuclear power plants.

Radioactive waste is a byproduct of nuclear reactors, fuel processing plants. Radioactive waste is also generated while decommissioning and dismantling nuclear reactors and other nuclear facilities.

The radioactivity of nuclear waste lasts for at least 10,000 years, so nuclear waste must be stored for a long period that raises many ethical questions and issues. Building storage for this waste requires an ability to envision what society, the environment and their interaction would be like in 10,000 years and more. This is not an easy practice and may lie beyond human imagination, as illustrated from examples in Finland and the Netherlands.

Finland is the first country to build a final disposal facility for nuclear waste. In 2004, in Eurajoki, the first geological final disposal facility – called Onkalo – started construction to store waste underground for as long as needed. Scheduled to commence operations in 2025, this nuclear waste repository is expected to hold approximately 6,500 tons of spent nuclear fuel. An underground research facility at 455 meters deep beneath the ground was constructed between 2004 and 2014 to verify the suitability of the bedrock.

A study was conducted on the sociotechnical issues that came along with the site selection process for the final disposal facility. The study found that the site for building the final disposal facility in Finland was chosen not just based on geological suitability but mostly on the lack of opposition from the local people and government.

In the 1980s, nuclear energy companies and the Finnish government started to look for a site where a final disposal facility could be built. There was a lack of meaningful participation from stakeholders in the selection of the site. In the end, the government picked a municipality with less opposition, namely Eurajoki.

Gaining acceptance and trust among the residents was quite easy in Eurajoki as they were already familiar with the nuclear industry, due to the presence of the Olkiluoto nuclear reactors there.

Moreover, the municipality was in favor of building the final disposal facility as it would receive financial compensation significant enough to help it deal with local financial issues.

Scholars argued that geologically, Eurajoki was inadequate for the long-term storage of radioactive nuclear waste. In 10,000 years, when the final disposal facility will be covered by ice sheets for several thousands of years, permafrost can penetrate deeper than the nuclear waste disposal site, which will result in strong pressure that may destroy the nuclear waste canisters at 450 m deep.

Despite the criticism, the site selection process continued.

In the Netherlands, there is currently a temporary nuclear waste storage facility in Borssele that will last for 100 years. The Dutch government decided to postpone selecting the site for a final disposal facility until 2100 because it wanted to avoid public opposition and resistance, which may hinder the search for a suitable site and cost the politicians their bid for reelection.

The two cases show that a (final) disposal facility requires advanced technologies, a long construction process, selection of suitable geological sites, as well as sociopolitical support because of implications of the decision on future generations.

There are also long-term risks regarding the transfer of disposal information over time. Failure to communicate the risks with the public may lead to a disaster. There is a chance of future generations discovering the nuclear waste disposal sites and exposing the radioactive waste out of ignorance or curiosity, which could trigger global risks.

After hundreds of years, when nuclear energy companies no longer exist, technical and geological information regarding the risks of the final disposal of nuclear waste should be handed over to future generations. This process will be very challenging, not in the least because the language that is spoken today will likely change drastically, as well as the ways we communicate.

Signs or cryptograms that are currently considered the best way of communication will not guarantee that essential information about the risks and locations of nuclear waste can be passed on after 10,000 years. Hence, when nuclear waste is disposed of, it is essential to think about the long-term plan that is needed to store nuclear waste in such a way that it is safe for future generations.

Recovery strategies after the pandemic must be sustainable and resilient, considering the complexity of interconnected (global) risks in the future. Therefore, planning new nuclear reactors should take into account long-lasting nuclear waste storage to protect (future) societies. The external costs (externalities) or uncompensated social or environmental effects will be much higher if preparations are poor.

Further research is required on geological suitability (considering earthquake risks) in Southeast Asia and the readiness and capability of stakeholders in dealing with the risks of nuclear waste. Some studies argue that the way of thinking and practices on risk management in energy sectors in Southeast Asia remain relatively low, such as the lack of risk assessment.

Many energy projects in the region still pose ethical risks, such as environmental and social impacts, and vulnerability to conflicts, which will adversely impact supply chains ranging from mining and production to waste disposal.

We should not repeat the same old story. In the 1800s, our ancestors started fossil fuel industries that today cause climate change. Never start a new industry without considering risk management as it would lead to another global disaster in the future.

***

Vita Verwaaijen is an independent researcher based in Amsterdam and Ibnu Budiman is a former research consultant at ASEAN Centre for Energy, Jakarta.