Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsProtecting Indonesian fishermen

In the complicated maritime boundaries between Indonesia and Australia, educating fishermen residing around the border areas is now more pressing than ever.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

any in the country seem unaware that Australian authorities burned three Indonesian fishing boats on Nov. 8, somewhere close to the Rowley Shoals Marine (RSM) Park off the Western Australian coast, for alleged poaching. But it was not the first case of incursion into Australian territory by Indonesian fishermen.

However, let us observe at least five points before judging whether or not Australia’s recent action was acceptable. First, we need to understand the status of maritime boundaries between the two neighbors.

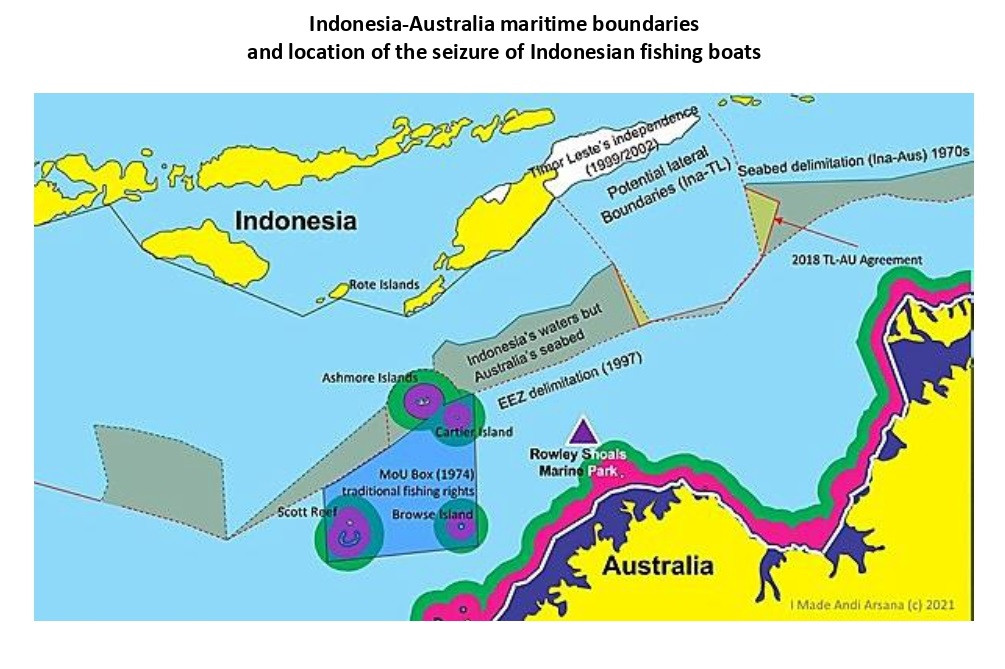

It is clear that Indonesia and Australia have established maritime boundaries between them. The border of the seabed, or the continental shelf, was established in the 1970s, while the water column -- for the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) -- was divided in 1997. With these established borders, it is easy to determine whether or not a fishing boat operates legally.

Second, the position matters. The question is whether the Indonesian fishing boats were operating in Indonesian waters or those of Australia. Unfortunately, information regarding the precise coordinates of the place where the boats were intercepted is not available.

Australia claimed the incident took place near the RSM Park. According to the coordinates on the official website of Western Australia’s RSM Park and a check on Google Maps, the position of the boats was clearly south of the EEZ boundary line between Indonesia and Australia, which means the incident took place in Australian waters.

Third, it is worth noting that maritime boundaries between Indonesia and Australia are complex, typified by differences between lines dividing the seabed and water column. Because of this, there is maritime space where the seabed falls within Australia’s jurisdiction but the water column above it is part of Indonesia. In other words, resources of the water column, including fish, are for Indonesia to harvest but oil and gas under the seabed for Australia.

Another point to note here, is that sedentary species like sea cucumber belong to the seabed. Sedentary species, according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Article 77 (4), are “organisms which, at the harvestable stage, either are immobile on or under the seabed or are unable to move except in constant physical contact with the seabed or subsoil.”

In this situation, Indonesian fishermen are entitled to capture fish in the abovementioned area, but it is illegal for them to capture sea cucumbers. However, this has nothing to do with the current case because, once again, the incident clearly took place in Australian waters.

Fourth, Indonesia and Australia have an agreement where Indonesian traditional fishermen are allowed to fish in certain Australian waters around Ashmore Reef. It is based on an agreement signed in 1974, officially known as the “Australia-Indonesia Memorandum of Understanding regarding the Operations of Indonesian Traditional Fishermen in Areas of the Australian Fishing Zone and Continental Shelf – 1974” (MoU Box 1974). Indonesian fishermen are allowed to fish within the box. When first hearing about the burning of the boats, I thought the fishing activity took place within the 1974 box, but I was wrong. The activity was clearly outside of the box, so we cannot refer to the provision where traditional Indonesian fishermen are allowed to fish within Australian waters.

Fifth, incidents involving Indonesian fishermen and Australian authorities are not new. For many reasons, law enforcement in maritime areas between Indonesia and Australia has been taking place for a long time.

When I was in Australia pursuing my master’s and doctorate degrees, I often heard our diplomats at the Indonesian Embassy or consulate generals deal with such incidents. It seemed that economic factors were often the main reason for the fishermen's breaching, which is why the Indonesian government needs to positively intervene to help our fishermen.

But back to the question above – is the burning of Indonesian fishing boats acceptable? It is quite clear that the boats were operating within Australian waters when they were captured. It is hard to deny that the fishing activity was illegal.

However, one can always question whether there is a better solution than burning the boats. Will such tough action be an effective deterrence? We can debate over the issue, but one thing for sure is that Indonesia also takes a similar approach against illegal fish poachers. Exploding or sinking boats caught illegally fishing in Indonesian waters has been the preferred approach since 2014, when Susi Pudjiastuti was appointed Maritime Affairs and Fisheries minister.

So when responding to Australia’s approach, Indonesia cannot apply a double standard.

It would be more productive for us to look forward. Close collaboration between Indonesia and Australia is a must to prevent this incident from recurring. Having an agreement on how to handle fishermen operating illegally can be a feasible solution.

In addition, education for fishermen and patrolling officers should be more substantial. In the complicatedly arranged maritime boundaries between Indonesia and Australia, it is not surprising to see fishermen have difficulties comprehending the situation. A lack of understanding can easily lead to violations.

Therefore, educating fishermen residing around border areas between Indonesia and Australia is now more pressing than ever. This is certainly also the case for people settling in maritime borders with other neighbors.

In short, we are responsible for protecting our fishermen. First and foremost, the government should protect them economically. Second, we should protect them with adequate knowledge. Hence, frequently arranged information, knowledge dissemination or sharing can be of help. For this purpose, nonstate parties such as researchers, lecturers, students and NGOs can and should be involved.

***

The writer is a lecturer and researcher in geospatial aspects of the law of the sea at the Department of Geodetic Engineering, Gadjah Mada University. The views expressed are his own.