Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDesperate times: How COVID-19 drove ordinary people to crime

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he COVID-19 pandemic triggered a massive job crisis that left millions unemployed, with very few legitimate options to put food on the table. The Jakarta Post spoke to three individuals about how they resorted to crime just so they and their families could survive.

Moch. Jinar Ridwan is a 37-year-old father of two young children, an infant and a toddler, who lives in Jombang, East Java. He used to sell bakso (meatballs) until COVID-19 arrived and left him without a job.

“Before the pandemic, I sold meatballs in several areas in Jombang to earn a living. However, the pandemic made me lose my source of income,” Jinar said on 29 Sept. 2021, during The Jakarta Post’s visit to Jombang Penitentiary, where he is serving his sentence for a burglary conviction.

Jinar used to earn between Rp 90,000 (US$6.33) and Rp 100,000 each day from selling bakso. When the pandemic hit, his income decreased drastically to Rp 25,000 per day, mostly as a result of the government’s variously named policies to restrict community mobility and curb the virus’ spread.

“That Rp 25,000 was not my net income. With that money, I still had to buy cigarettes for myself and plastic wrap for the bakso,” he recalled.

The former bakso seller stole electronic devices like LCDs and computer hard drives from 23 different schools in Jombang. He started stealing in January, and his last heist netted him Rp 30 million in equipment from SDN Podoroto elementary school in mid-September, when the local police caught up with him.

Jinar said he received Rp 300,000 in monthly social assistance from the government for just three months, after which the aid stopped coming. He said he was too ashamed to ask his neighborhood unit (RT) head about it. That was when he started targeting schools to steal electronic equipment that he could resell for cash.

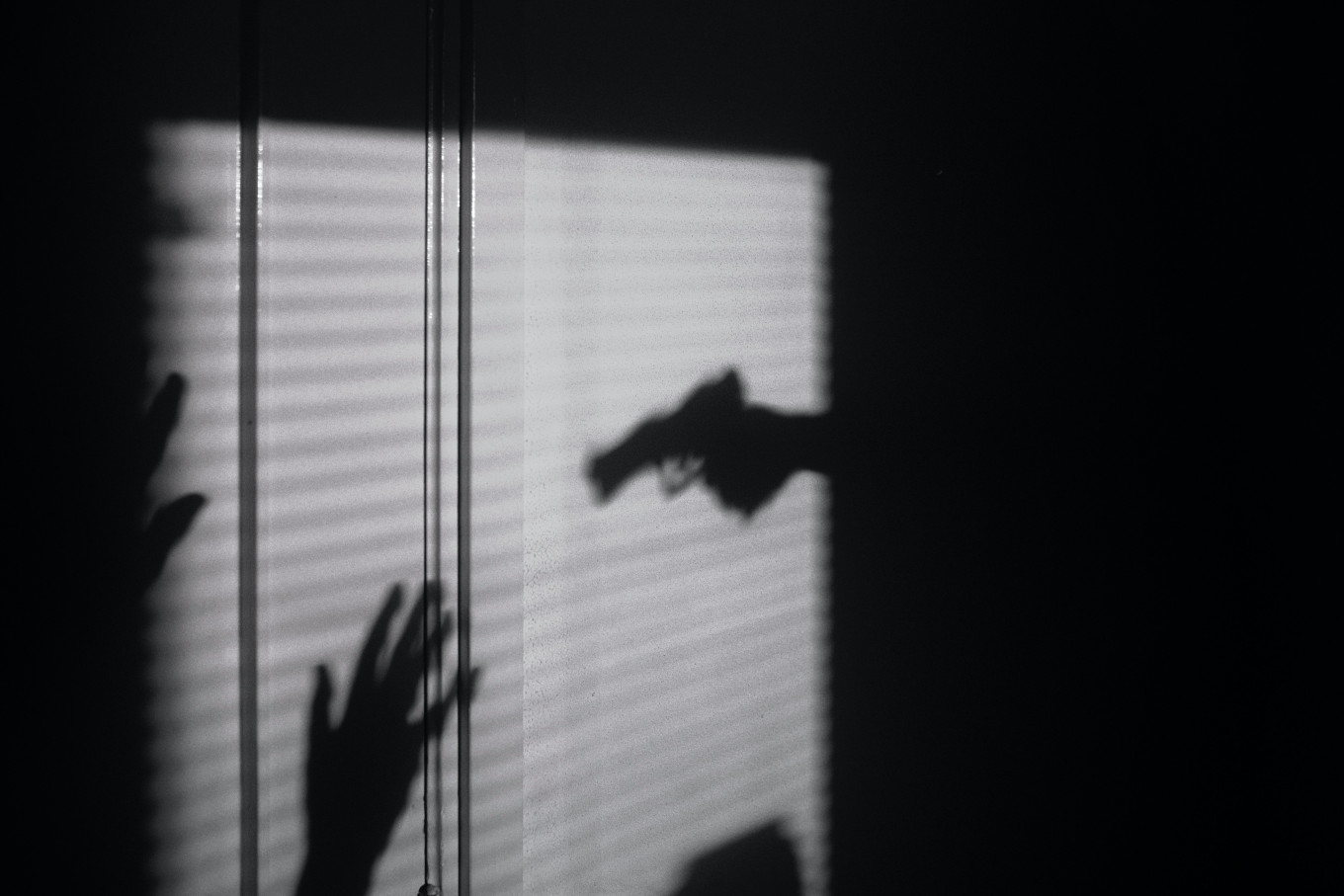

Stock illustration of armed burglary. Some Indonesians have turned to crime to survive the pandemic that left them without incomes or new job prospects. (Unsplash/Maxim Hopman)Jinar told the Post he originally planned to burgle just one school so he could support his family. Still without a job, however, Jinar found himself unable to stop. It didn’t help that he was making far more from just one burglary than he ever did as a bakso seller.

According to Jombang Police investigator Brig. Dwi Ari Suryanto, Jinar surveilled the schools he had targeted before carrying out the theft. Jinar mostly targeted schools that were padlocked on the outside, Dwi said, because he knew then that the school did not have on-site security.

A case like Jinar’s was ineligible for sentencing based on the concept of restorative justice, said Jombang Police chief Brig. Lukman Hardiyanto, as he had committed the same crime on 23 separate occasions, enough to put him behind bars for up to seven years.

“To grant restorative justice, we always need to [review] the situation. First, we can grant it if the [crime] is not repeated. Second, the perpetrator must report [their movements] to us every Monday or Thursday,” Lukman told the Post.

It is unclear who is taking care of Jinar’s family while he is in jail.

Driven to shoplifting

Marsini, 55, and her niece Yulianti, 29, were temporarily apprehended though swiftly released as a result of restorative justice for shoplifting on Aug. 31 in Blitar, East Java.

During a visit in late August to her modest home in Malang, East Java, Marsini shared how she and Yulianti ended up stealing a box of formula milk, a bottle of cajuput oil, a common ointment used to treat headaches, pains and fever, and bottled water from a mini market in Blitar, East Java. They were granted restorative justice and told to reconcile with the shop owner, as neither had a criminal record.

The Blitar Police also police gave them Rp 1 million to buy milk for their children as well as five boxes of formula milk.

“Initially, I did not want to steal. We went to Blitar to ask my brother-in-law for financial assistance during the pandemic. But by that time, my brother-in-law had passed away and no one could help us anymore. We didn't even have the money to return to Malang, with only Rp 14,000 in our pockets,” said the mother of five.

Marsini previously sold jenang and cilok traditional snacks to earn a profit of between Rp 25,000 and Rp 50,000 each day. She had survived on this income for over 20 years, but things came to a head when the pandemic hit. Her husband Roman, 54, lost his job as a ragman that earned him Rp 50,000 on a good day. He also fell ill and became unable to walk.

[ga:2]

Yulianti’s story is similar. “I did not have the money to buy milk for my 4-month-old baby. My husband was unable to help us either, because he made money from [an informal job] directing traffic on the street and needed to rotate [shifts] with 12 other people,” said the mother of three.

Her husband Sugiono, 46, lost his job as a result of the COVID-19 mobility restrictions and now busks on the street, bringing home around Rp 50,000 every day.

“For the last few days, our baby has had a fever. He has not been taken to the doctor yet. If both of us cannot earn money, we cannot provide a living for our family,” said Yulianti, who had already tried her hand at selling toys in front of an elementary school in Malang.

“I have never received social assistance from the government,” said Marsini. “Maybe it's because I don't have a fixed address and we need to report our new addresses to the RT [head], and this would be very troublesome for me.”

Yulianti said her situation was the same.

Social awareness & empathy

Criminologist Dr. Prija Djatmika from Brawijaya University believes that more empathy is needed regarding the desperation of lower-income Indonesians.

"I don't think these crimes can all be resolved [with prison sentences],” he said, pointing to cases in which the poor were jailed for a long time for petty theft.

“If we always charge people without looking at their [life] conditions, it will not solve the problem. Because we have a huge welfare problem, we need social assistance for less fortunate Indonesians,” Prija continued.

He noted that the people could not always rely on the government to help, but as a society, the more fortunate needed to be aware of those who were less fortunate.

"If the government [tries] to help [everyone], let’s face it, it will not work, because we have a huge population. The economy is stagnating and income is lacking, while the [welfare] needs of the lower class are very high. This cannot be handled by the government alone. So social action from the community is also very important,” he stressed.