Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIndonesia as a democracy model

Indonesia is emerging, in some ways, as a model democratic polity for the Islamic world and some of its neighbors

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

ndonesia is emerging, in some ways, as a model democratic polity for the Islamic world and some of its neighbors. For instance, in the politically troubled Thailand, it is seen by some as showing the way. In a recent op-ed piece in the New York Times, Prof. Thitinan Pongsudhirak of Chulalongkorn University wrote, "For all the country's troubles, Indonesia's transition to democracy after decades of autocratic rule may offer the best model."

During her recent Indonesia visit, US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, paid fulsome tribute to Indonesia both as a democracy and a moderate society. While in Jakarta, she said, "If you want to know if Islam, democracy, modernity and women's rights can coexist, go to Indonesia."

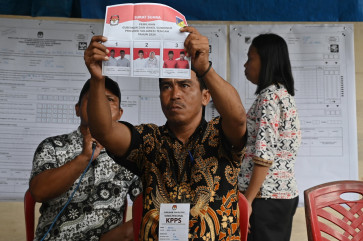

It might seem a bit overblown but, considering that Indonesia was racked by terrorist violence only a few years ago, its present relative stability is quite amazing - at least to an outside observer. The parliamentary elections in Indonesia would validate some of these claims. In the first place, the elections (with presidential election to follow in July) would suggest that Indonesia's democracy continues to mature.

This is not to say that Indonesia has arrived at some sort of political nirvana. All the usual problems of political horse-trading and corruption are very much there. What is different, though, is that there is a certain diffusion of power within an increasingly de-centralized polity, subject to some level of accountability and scrutiny.

Under Soeharto, it was largely his show with corruption concentrated in the ruling family and their cronies. At times, though, with the stench of corruption still fouling the air, the present order doesn't seem like much of a change. And this is because the media and other public forums are now free to talk about it all. Which is a positive change.

Under Soeharto, even though the venality and corruption under his rule was widely known, it was not a matter of public debate.Democracy, of course, is a messy business. Indonesia's problems are massive, with large-scale unemployment made worse with the global economic crisis. And there are no easy solutions.

But popular participation in the electoral process does empower people to question their leaders and seek better performance and standards. In this sense, they become accountable to those who have elected them. Let us see how it is this working in practice. According to the Indonesian Survey Institute, there has been a drop of about 12 percent in the voting strength of major Islamic parties from 38 percent to about 26 percent.

Even though the Prosperous Justice Party has marginally gained over their 7.2 percent vote showing in 2004, it is less than half of what they were aiming at around 15 percent mark.

The simple explanation is that all their loudly proclaimed credentials of honest and righteous governance came tumbling down once they became part of the coalition government of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and also won some governors' offices.

They got embroiled in corruption and political venality. The advocacy of Islamic ideals and practices started to look more like political slogans and symbols. In this way, they became indistinguishable from the run of the mill politicians.

Indeed, compared to them, Yudhoyono's anti-corruption drive (for whatever it is worth) seemed more appealing. No wonder then that Yudhoyono's Democratic Party made important inroads into the Islamic parties' electoral territory.

In any case, Indonesians, by and large, are not given to extremism of any sort and tend to regard religion as a matter of personal faith.

Against this backdrop, all the talk of Shariah law and banning pornography with its broadest brush to tar almost anything as un-Islamic, hasn't carried much sway with the voters.

This is not to suggest that Islamic parties have lost their political resonance. Altogether, they still poll more than a quarter of the total vote and, with some fine political tuning, they can sill expand their political territory. The point to make is that with their eclectic cultural traditions, Indonesian voters are more discerning to be carried away by harsh images of Islam.

The strong showing of his Democratic Party would suggest that Susilo should have no difficulty with his re-election in July. There might be some problems from the falling off with the Golkar Party over their vice-presidential nominee.

But if he is returned as President for another term (which seems likely) with his position strengthened and a strong parliamentary hand, this might encourage him to go boldly for some radical transformation. Indonesia needs a strong President. Susilo filled the bill in his first term as a conciliator, not keen on rocking the boat.

But, in his second term, with fewer political constraints and a stronger mandate, he will be well placed to do a bit of hard shaking to take the country forward.