Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhat became of Kalijodo's people?

“Deep inside my heart, I don’t get any benefit from it because I lost something,” Bang Joi said.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen bulldozers and excavators began to tear down the only home he ever knew in March last year, Bang Joi could not do anything.

The month before, he had received three letters from the Jakarta city administration, instructing him to tear down his residence and leave the area. He was given three months free rent in a government housing project — 40 minutes away from his family and friends — and no compensation. “They took away people’s lives,” he said.

Bang Joi, not his real name, grew up in what was then Jakarta’s biggest red-light district, Kalijodo.

The 29-year-old lived there his entire life, until it was demolished to be redeveloped into a green space for families.

At the time, Kalijodo was rife with prostitution, illegal bars and criminal gangs. City administrators had been promising to tear it down for years.

Read also: Kalijodo shutdown: Requiem for a legendary red-light district

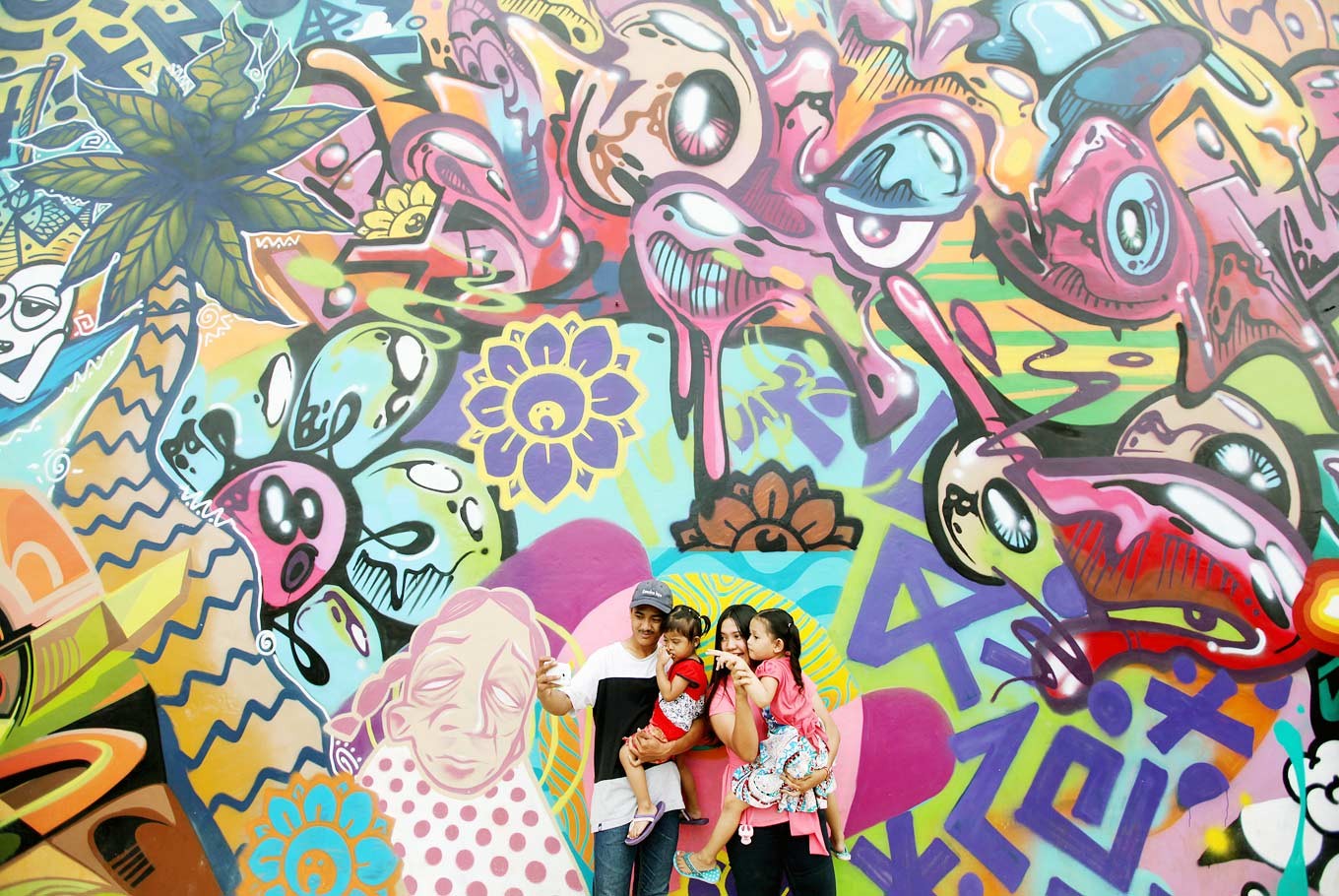

Now, Kalijodo is home to a large skate park for children, and on weekends, market stalls sell food and drinks to families who come for the live music and children’s rides that sit where people’s houses once stood.

Joi has returned several times to his former home, and although the new park was great for families, he felt something had been taken from him.

“Deep inside my heart, I don’t get any benefit from it because I lost something,” he said.

“When I pass the park, I see people are enjoying it -- but I don’t. Imagine if it was you. It’s your house […] other people are occupying your house.”

Mba Sum lived in Kalijodo for 20 years and worked as a caterer to the many cafés in Kalijodo.

After the demolitions, she was forced to return to her hometown in East Java, where she works selling vegetables in the town market.

“I’m having a hard time making money. I’m grateful for just being able to eat,” Sum said.

She questioned why a whole community had to be wiped out just because of a few bad apples.

“It’s unfair. Prostitution didn’t stop. It just moved to other places and dispersed just across the park,” she said. “If the problem is the cafés, then just get rid of the cafés, not the people.”

It is a sentiment Joi agreed with.

New face: Kalijodo is currently home to a large skate park for children, and on weekends, market stalls sell food and drinks to families. (JP/Seto Wardhana)“There are a lot of other prostitution places but why Kalijodo?” Joi asked.

The demolition has also affected business owners in the area, with most reporting a severe drop in their business. One couple even said they had lost nearly 50 percent of the customers in their food business since the redevelopment.

Another business owner, Judas Lim, said if business did not pick up soon, he would be forced to move somewhere else.

But despite this, the majority of businesses were positive about the demolition, saying the streets had been made safer by pushing out the thugs that once ran the area.

And yet, even though the criminals were supposedly driven away, their influence is still felt strongly in the streets around Kalijodo and even beyond.

Many businesses still did not wish to speak for fear of violent reprisals from former thugs, whom they claimed were still in the area.

Even Bang Joi chose to be known by a pseudonym out of fear of a similar reprisal, despite living more than 40 minutes away from his former home.

“I’m scared that the thugs are still out there until now and would try to find me,” he said.

Joi said people are still angry over what happened, and many believed they were lied to.

Before the relocations began, then-North Jakarta mayor Rustam Efendi told The Jakarta Post his administration would offer skills training to residents who wished to change their professions.

But both Joi and Sum said the promised training never happened. Attempts were made to contact the mayor’s office for comments on these allegations, but to no response.

Currently, Joi has found himself a job at a supermarket. Despite the situation, he is simply trying to move on with his life.

***

Dominic Elsome, a journalism student from the Queensland University of Technology, visited Indonesia with support from the Australian Government’s New Colombo Plan mobility program. Natasha Harianto and Clarissa Adeline contributed to the story.