Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBreaking the cycle of corruption

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

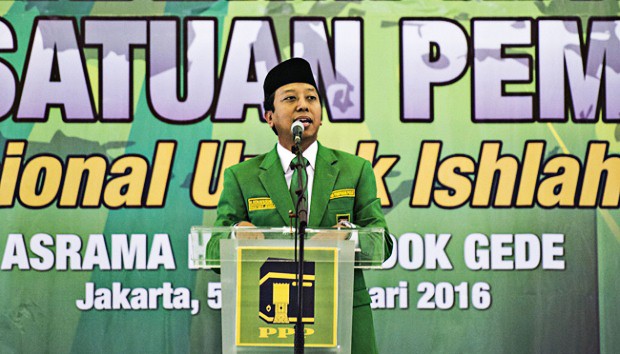

he arrest of United Development Party (PPP) chairman Muhammad “Romy” Romahurmuziy just a few weeks before the elections has surprised many.

The event, however, is by no means shocking. Such scandals have become too familiar and the public now reacts not only with disgust, but also with a sense of helplessness, if not apathy, because another politician has been arrested for graft.

Romy is not the first party leader (not even the first PPP boss!) to be charged with corruption. Prior to his arrest on Friday, the Corruption Court had convicted four political bigwigs: former Democratic Party leader Anas Urbaningrum, former Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) leader Luthfi Hasan Ishaaq, former PPP leader Suryadharma Ali and former Golkar Party leader Setya Novanto.

Romy, who was elected to replace Suryadharma following the latter’s arrest in 2014, has been accused of accepting bribes from civil servants to rig the promotion system at the Religious Affairs Ministry, which has long been considered one of the most corrupt institutions and is currently led by a PPP member. The scale of corruption in Romy’s case pales in comparison to those of Anas and Setya, who were convicted of rigging government projects worth millions of dollars. Romy has been accused of accepting a Rp 300 million (US$21,045) bribe.

Having said that, there would be no excuse for Romy doing anything like that, if he is indeed guilty. He allegedly abused his power to enrich himself or others. The scandal has practically ended his political career and put the Islamic party, which has fared poorly in many political surveys, in an even more precarious position ahead of the April 17 elections.

This is a classic story of a rising Indonesian politico.

Indonesian politics is plagued with corruption. Some say greed for wealth and power is the root cause for it; others blame the high cost of elections. Whatever the answer is, it appears that the current political system was designed to create a cycle of corruption that is nearly impossible to break, or that it only attracts people who are incapable of suppressing their appetite for illicit money.

No wonder that many Indonesians believe politics is inherently dirty and that it is just a matter of time before the antigraft body catches another politician. However, alas, we cannot afford to prolong such a defeatist attitude.

Corruption has hijacked Indonesian democracy. It has stripped the nation of all the benefits that it could reap from a free election. It has been more than 20 years since the beginning of the Reform Era; we should never let political corruption be the norm.

Romy’s fall from grace is regrettable. Like Anas, the 45-year-old was a promising young politician who many believed could bring about change in the country. His downfall, seen from another angle, is also a national tragedy.

It is not impossible to break this cycle of corruption. We can start by reforming the campaign and political party financing system and punishing the parties — nationalist or Islamist — that keep electing corrupt leaders.

A graft-free Indonesia should not merely be a utopian dream.