Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA lesson from Singapore's TOD

As a testament to the efficacy of TOD, one can look to how Singapore successfully leveraged it. The city-state shares many similarities and challenges with Indonesia’s metropolitan areas, such as traffic congestion.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

S

ome of the world’s most bustling cities are in Asia, with 44 million people moving through Asia’s cities every year. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), 80 percent of Asia’s new economic growth will be generated through these urban economies. These growth trends place a huge strain on urban transport and mobility — time loss and transport costs alone are estimated to be 2 to 5 percent of Asian economies’ annual gross domestic product.

To support the growing demand for modern urban transport systems, Asian cities are heavily investing in the construction of roads and quality mass public transportation. However, government budgets are often insufficient to support the large pipeline of projects.

To overcome this hurdle, private capital is often presented as a supplementary and alternative source of funding. To mobilize private capital to deliver urban transport, there is a need for newer frameworks in the government’s planning to better leverage land value capture, while developing liveable transit-oriented cities.

Indonesia is one of the countries that faces these barriers. The government’s plan for new roads is a double-edged sword — while it will increase the mobility of goods and people, market access and business activities, it will also lead to a rise in demand for cars. With already congested streets, commuters often find themselves stuck in two to three-hour traffic jams. This not only affects workers personally, but also factories and suppliers that deliver products to areas by land, ultimately leading to a decline in economic efficiency.

The transportation sector also contributes 70 percent of air pollution in Jakarta. Energy consumption of transportation in Greater Jakarta (Jabodetabek), Indonesia’s biggest and most strategic metropolitan hub, is more than 700 million kilo liters per year. In fact, the estimated economic cost of traffic congestion in Jakarta reached approximately Rp 960 billion (US$68.62 million) a year, excluding the cost of health impact to humans from transport pollution.

This is where public transport projects can make a difference by decreasing the number of cars on the road. However, funding these urban transit projects can pose a challenge. Public Works and Housing Ministry noted that the 2020-2024 state budget is only able to cover 30 percent (Rp 623 trillion out of the Rp 2,058 trillion) required for the infrastructure development. In view of this, what can be done to improve financing for public transport projects?

A key challenge that urban transport projects face is encouraging higher ridership. Most cities’ transport systems have already decentralized amongst private vehicles and operators, says World Bank Senior transport specialist David John Ingham.

Enter transit-oriented development (TOD) — a type of urban development that offers a strategic spatial planning tool to direct and regulate mobility in accordance with city’s development vision, says Arup specialist Kate Hardwick. Designed to maximize residential, commercial and entertainment space within walking distance of public transport nodes, it can help reduce competing transport options, while fostering a greater demand and viability for international investors in the design and operation of mass transport systems.

While TOD improves the liveability of cities, its effect on the financing model for mass transit projects is often overlooked. Integrated spatial and transport planning requires robust demand planning, as a well-planned urban transit line with robust traffic study lowers the risk of future deviation from ridership and cashflows projections.

Central state support is also a key factor in projects’ eventual bankability and investability, especially for new transport networks. Drawing from central states’ budget often requires the project to incorporate higher prudence in planning, stronger public connectivity outcomes, and a vision on the use of public transport to support the long-term development of the city. These conditions can help to mitigate demand risks to the private sector, improve the project’s economics and reduce the amount of the viability gap funding needed from public budgets.

For the above benefits to be realized, the international industry believes that the “successful implementation of a TOD project requires a robust feasibility study that takes into account stakeholders’ acceptance of the developmental proposition upfront,” says KPMG’s principal for Global Infrastructure Advisory, David Ng.

In Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital city, the administration has already expressed its intention to work on a significant number of TOD projects to transform stations and bus terminals into multimodal transport nodes that will integrate housing and public transportation. The plan also aims to maintain the availability of green open space for the urban ecosystem.

By looking abroad, Jakarta could adopt best practices from other cities on harnessing TOD, to fully realize its TOD vision, as well as engage with solution providers based in the region who have the necessary experience with such projects.

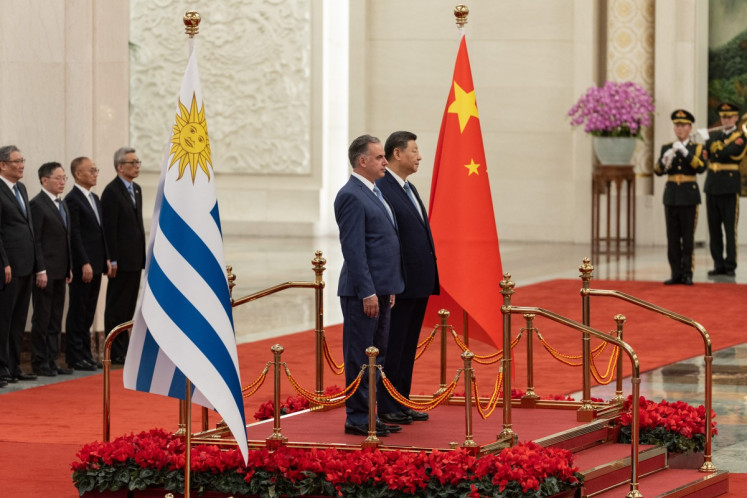

As a testament to the efficacy of TOD, one can look to how Singapore successfully leveraged it. The city-state shares many similarities and challenges with Indonesia’s metropolitan areas, such as traffic congestion. These conditions have prompted Singapore to integrate its urban transit development with spatial design and planning and could be one example for interested cities in the same region to leverage TOD for urban transport.

Singapore’s TOD is primarily focused on urban renewal through the expansion of the transit network. The result is a constellation of satellite towns that surround a central core, with rail networks that link these towns to industrial parks and the city center. These satellite towns are self-sustaining, with common public amenities within walking distance and a reduced need to venture out for common daily needs. Under the right conditions, TOD can also be used for discrete and promising projects rather than the entire network.

Singapore’s adoption of TOD also includes affordable public housing in well-connected areas.

Indonesia can tap into Singapore’s international ecosystem of firms with design, engineering and architectural experts. This also includes other key value chain players for transit-oriented cities such as active real estate firms, financiers active in seeking opportunities, and legal and transaction advisors who can help design and manage tenders up to its financial close.

By partnering with relevant organizations, Jakarta will be able to access the necessary investments for their TOD projects. Like it did for Singapore, leveraging TOD can help them encourage greater transit ridership by maximizing access to public transport and controlling the number of cars on their roads.

When the journey towards achieving transit efficiency is accelerated, costs, pollution and congestion all decrease significantly, to ultimately offer better quality of life for citizens.

____________________

Seth Tan is executive director and Poh Mei Yi is lead (Indonesia) of Infrastructure Asia