Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDecades on, Heri Dono continues to uphold his ideals through his art

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

For renowned artist Heri Dono, the archives of materials related to his work are as valuable as the works themselves.

At his studio in Yogyakarta, Kalahan Studio, Heri Dono not only turns his imagination and fantasies into astonishing art, he also maintains archives that follow the trajectory of his 41-year artistic career – from his days studying fine art at the Indonesia Art Academy (ASRI) to when he began to receive more widespread recognition.

The archives include diaries, books, letters, photos, journals, sketches, videos and newspaper clippings. Heri has collected them since he was a student at ASRI – now the Indonesia Art Institute (ISI) Yogyakarta – in the 1980s.

Heri is one of Indonesia’s most influential contemporary artists. He is known for expressing critical thoughts on social, economic and political issues through his paintings, performance art and installations.

Since 1990, he has participated in 35 international biennales and more than 300 exhibitions at home and abroad, with numerous accolades under his belt, including the Dutch Prince Claus Award from the Dutch government in 1998, the UNESCO Prize in 2000 and the Visual Arts Award from the Indonesian government in 2014.

Heri recently displayed selections from his archive at Srisasanti Gallery in Yogyakarta as part of a solo exhibition entitled Phantasmagoria of Science and Myth, from October 2021 to January 2022.

Attractive installation: The "Unidentified Unflying Objects" installation depicts five astronauts with five characters inside the helmets, including a monkey, Semar, General Sudirman, Marylin Monroe and Albert Einstein. (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung) (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung)The exhibition also showcased Heri’s more recent work, including a 45-minute documentary titled The Enigma of HeDonism. Screened regularly during the exhibition, this documentary won Best Indonesian Feature-Length Documentary at the Yogyakarta Documentary Film Festival (FFD) in November 2021.

“Artists do not live forever. When they are still alive, they can hold artist’s talks. But [after they die], let the archives talk,” the 61-year-old said.

“If people want to do research about me or my work, they do not need to interview me. They can read these archives,” he added.

Challenges

For Heri, the studio is a laboratory for the production of new thoughts through art, which may represent stances on important issues.

His archives not only highlight those thoughts but also show the challenges that he has met in his years as an artist.

Heri’s idealism caused him to drop out of ASRI in 1987 and receive a number of rejections from galleries, such as the Lisson Gallery in London in 1996, as well as pressure from the authoritarian New Order regime.

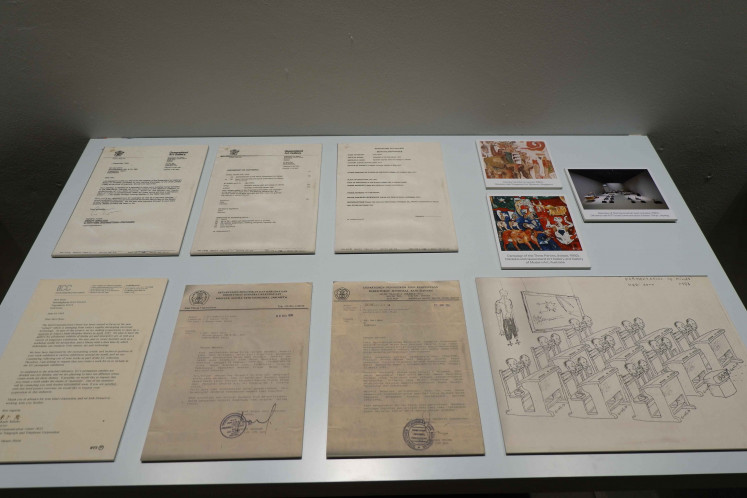

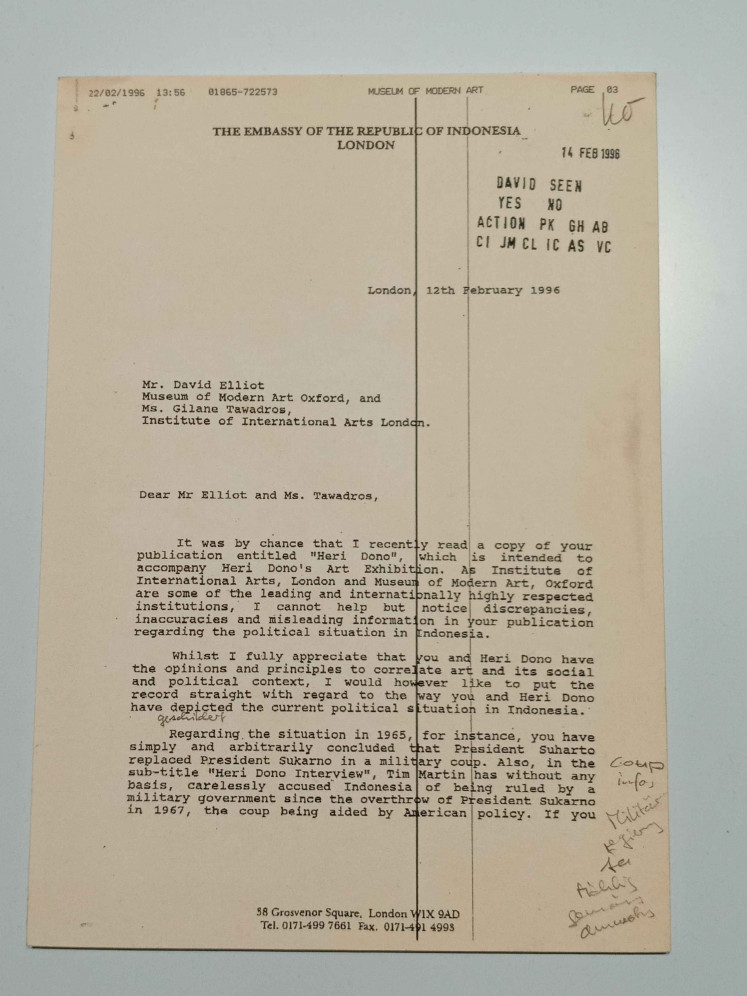

Among the archives are the Embassy of Indonesia in London’s furious letter in February 1996 to curator David Elliott of the Oxford Museum of Modern Art and Elliott’s response letter to the embassy.

In the letter, the embassy demanded Elliott withdraw the catalogue books of Heri’s art exhibition at his museum.

Archives: Since he was a student at the Indonesia Art Academy (ASRI) in the 1980s, artist Heri Dono has archived items related to his career, including letters from government and nongovernment institutions. (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung) (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung)The government objected to the catalogue because it contained what the government called “discrepancies, inaccuracies and misleading information about the political situation in Indonesia”.

“[Writer] Tim Martin has, without any basis, carelessly accused Indonesia of being ruled by a military government,” read the embassy’s letter.

From the Indonesian government’s perspective, the catalogue was propaganda because, among other things, it stated that president Suharto had overthrown president Sukarno in a military coup that was aided by United States foreign policy in 1965.

In his letter, Elliott defended Heri, saying that, “Art is not the same thing as propaganda, and you are incorrect in thinking that Dono is involved in this.”

For Heri, the two letters are memorable. After returning to Indonesia in 1996, he was arrested and interrogated by the authorities for three days.

Furious letter: A letter sent by the Embassy of Indonesia in London to David Elliott of the Oxford Museum of Modern Art in 1996 makes up part of the archive. In the letter, the Indonesian government expresses anger at Elliott for information written in the catalogue book of Heri Dono’s exhibition at the museum. (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung) (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung)Criticism

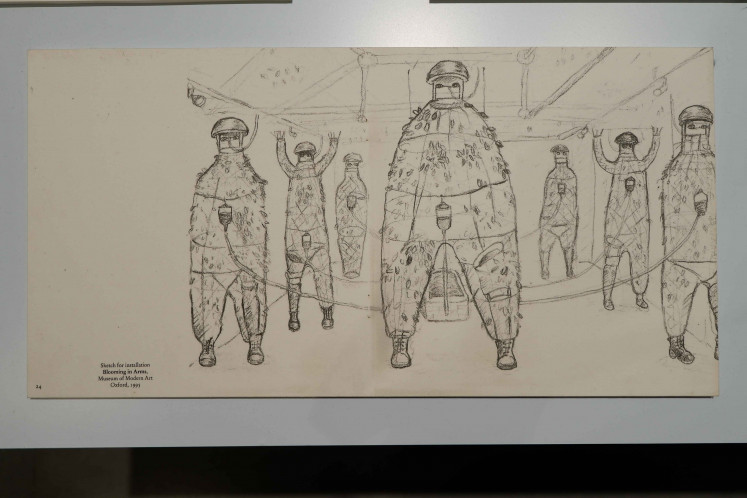

As an artist, Heri has always been critical. When he was 35, in 1995, for example, he lampooned the New Order administration’s “green program” in his installation entitled “Blooming in Arms”.

Heri thought the green program was a farse. On one hand, the government had ordered people to plant trees and vegetation in front of their houses to create a ‘green’ atmosphere, but on the other hand, it was permitting big companies to decimate forests in Sumatra, Kalimantan and Papua.

He believed the military-dominated rule during the New Order was behind the program. Therefore, “Blooming in Arms” had artificial legs that symbolized devastation caused by militarism, with army boots and helmets to symbolize the ghosts of militarism.

Design sketch: Heri Dono is still saving the design sketches that he makes for his exhibitions at home and abroad. One of them is a sketch for the "Blooming in Arms" installation that he exhibited at the Oxford Museum of Modern Art in the United Kingdom in 1995. (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung) (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung)Even today social, economic and political issues remain his concern. In his new painting entitled “The Trojan Komodo Met Glass Vehicles”, for example, he raised the issue of global warming and other forms of environmental destruction, which he said were caused by capitalism and urban development.

“Trash has polluted the sea and poisoned sea animals. These animals are then consumed by us and this then causes disease in our bodies,” Heri said.

“The Trojan Komodo Met Glass Vehicles” depicts a cartoon character named Trokomod, a portmanteau of Trojan Horse and Komodo dragon, with a humanoid figure watching a television inside an erupting volcano and alien and wayang (puppet) characters flying to the mountain.

Medium of expression: Titled “The Trojan Komodo Met Glass Vehicles”, this painting criticizes global capitalism, which Heri Dono believes has caused environmental issues around the world. (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung) (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung)Heri’s distinct cartoons, which look frightening but comic, are often part of his work. He said he liked to use cartoons to deliver humor, irony and ridicule.

He attributes this tendency for his great love of wayang performances and comic books. He said they had helped him develop his imagination.

“Cartoons, comics and wayang influence my creative process when I am making parodic and humorous works. A humorous work is not always like farce a la Petruk and Gareng [popular characters in Javanese wayang] but it can be translated into colors and lines,” he said.

Benefits

For noted art critic and curator Jim Supangkat, Heri Dono’s archives are important for society because they are useful for discussion and research.

The extent of the archives, Jim said, was exceedingly rare in the Indonesian art scene and was surprised by the orderliness of the collection.

“[In other places in Indonesia] like museums, documents are in disarray. That’s why foreign researchers who come to Indonesia to research Indonesian history will meet with difficulty when searching for the documents they need,” Jim said.

Heri’s perseverance in archiving, Jim said, also played part in helping him earn the respect of art communities overseas. The completeness of his archives made it easier to understand and assess his work and creative process.

Index of history: A visitor reads a selection from Heri Dono’s archives at the Srisasanti Gallery in Yogyakarta. (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung) (JP/A.Kurniawan Ulung)“Heri Dono is the only Indonesian artist to get recognition from an international fine arts circle,” Jim said, adding that Heri’s work was collected by renowned museums overseas.

ISI Yogyakarta lecturer Suwarno Wisetrotomo said Heri’s archives were proof that he was “futuristic” because he had been aware since his early career that his archives would be useful.

“His archives are hard facts that show his existence in the art scene. They confirm all the achievements that he has gotten and the rocky road that he has gone through” Suwarno said.

Suwarno believed Heri’s archives would help make other artists across the archipelago aware of the importance of archiving and would inspire them to follow suit. He said Heri’s archives would also help people in general understand the importance of history.

“Archives will make us understand the connection between one event and another. Archives explain the life journey of an individual, a group, a community or even a nation or a state,” he said.