Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsAisyah's story: How books are changing lives

Across the vast archipelago of Indonesia, children are beginning to read not just for the sake of reading but for pleasure as well.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

eet twelve-year-old Aisyah. She fell in love with reading when her school created a mini-library in the classroom. Now, she brings books home almost every day to enjoy during her free time.

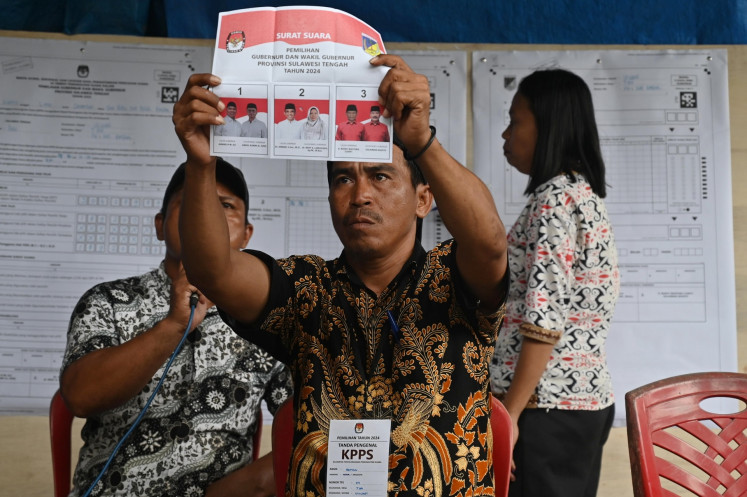

Aisyah is completing sixth grade at the State Primary School 1 in Allakuang, Sidenreng Rappang (Sidrap) district in South Sulawesi.

In just the first semester of this year, she read over 115 storybooks. This big achievement from a girl in a small farming town earned Aisyah wide recognition from district and provincial leaders.

It even caught the attention of the Indonesian Culture and Education Minister, who recognized her at an awards ceremony in Jakarta.

But what really makes Aisyah proud is the way she has taken her love of storybooks outside the classroom.

“I taught my mother to read,” she said.

“Praise be to God. My mother can read now….She has already read three books that I borrowed from my school,”

We recently met Aisyah at an awards ceremony in Jakarta, where she told her mother’s story to an audience of over a hundred people.

“My mother wakes up at four o’clock in the morning,” Aisyah explained.

Read also: Malang public minivans become mobile libraries

“After her prayers, she goes to work at the chicken farm. She collects eggs and feeds the hens. She finishes work at six o’clock in the evening and I bring books home from school for her to read. I help her to spell out the words. Sometimes, if she doesn’t come home during her midday break, I take books to the chicken farm,”

Aisyah’s mother, Ibu Anno, was unable to finish elementary school — a common reality in Indonesia for women like her.

Nowadays, while literacy rates are nearing 99 percent among school-aged youth, Indonesia still struggles to instil a passion for reading in its students.

In a 2016 report, Central Connecticut State University ranked Indonesia as 60th out of 61 countries studied for reading interest. Indonesia does not have a culture of reading. But all that is set to change.

The movement to create a reading culture in Indonesia is gaining momentum.

The Culture and Education Ministry, together with international partners, such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), is introducing fifteen-minute daily reading sessions for students in schools.

A love of reading is being fostered across the country. Many districts have declared themselves “reading culture districts” and introduced programs to build literacy.

Aisyah’s school is a partner of the USAID-funded PRIORITAS program.

“We have been encouraging the students to read. The fourth, fifth and sixth graders usually read about 45 books every semester, and the younger students are read to by their teachers,” the school’s principal, Muhammad Basri, said.

Readers unite: Aisyah and her friends read books in class during a 15-minute reading session before lessons start.(USAID Prioritas/File)

Readers unite: Aisyah and her friends read books in class during a 15-minute reading session before lessons start.(USAID Prioritas/File)

In addition to the wide range of books available, an awards program and reading logs encourage students to keep up their pleasure reading.

USAID has donated eight million books to 13,000 schools in Indonesia. These books build literacy as well as an appreciation for reading and help students like Aisyah, who wants to become a doctor, to get better education results.

Meanwhile, local non-government agencies are getting on board.

Read also: Literacy Award presented to 19 USAID-partner regencies, municipalities

For example, the Bali-based Literasi Anak Indonesia (Indonesian Children’s Literacy Foundation) has created sets of leveled books, designed to introduce children to reading. These attractive books, written and illustrated by Indonesian artists and writers, are carefully designed to be appropriate for young readers.

Working with the Indonesian government and international agencies such as USAID, UNICEF and Room to Read, the foundation has distributed its books to schools from Aceh to Papua.

And then there is Yayasan Taman Bacaan Pelangi (Rainbow Reading Garden Foundation), which has set up libraries and introduced over 100,000 books to children in eastern Indonesia. The foundation was established by Nila Tamzil, a young Jakarta woman with a passion for reading and education.

In Palangkaraya, central Kalimantan, there is another foundation called Ransel Buku (Book Satchel), established by Aini Abdul, another spirited young woman. The foundation has established a floating library, which brings the joy of reading into the lives of children in remote Dayak villages on the Rungan River.

Mobile libraries are also springing up all across the country — from local government-funded floating libraries on the islands of Pangkep in South Sulawesi to the Indonesian Military’s mobile book brigade in Abdya, Aceh.

Read also: The book is mightier than the gun

Teenage girls are creating a library with funding from the Australian government and charities in the impoverished village of Bungaya in Bali.

Mobile libraries are appearing in public transportation minibuses in Bandung, West Java, in jamu (traditional medicine) stalls in Sidoarjo, East Java, and on horse-back in Purbalingga, Central Java. And now the national government is supporting the movement.

At an event to celebrate National Book Day held at the Presidential Palace in Jakarta on May 17, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo announced that the government will support community-based libraries by providing free freight for books on the seventeenth day of every month.

These kinds of programs, whether government or grass-roots community initiatives, aim to get books into the hands of poor children, in places where there are no libraries and no bookshops. The aim is to encourage a love of reading, to create a reading culture.

Reading opens doors, opens minds and opens hearts. It is through reading for pleasure that children like Aisyah discover a world beyond their village, and, importantly, learn to see that world through the eyes of others — to experience different lives, different perspectives, different religions and ethnic identities.

In a world increasingly divided by mistrust and misunderstanding of people from different faiths and cultures, reading can be a powerful weapon for harmony.

— Handoko also contributed to this story.