Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsOrangutan conservation: Government agencies no 'cleaning service'

I really don’t understand the local conservation authorities. A protected species like the orangutan is on a rapid downhill trend toward extinction, but still the government does not implement any meaningful intervention.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

really don’t understand the local conservation authorities. A protected species like the orangutan is on a rapid downhill trend toward extinction, but still the government does not implement any meaningful intervention. Instead, it seems to envisage activities that hasten the decline of its most endangered wildlife.

A case in point is the extremely rare and critically endangered Batang Toru orangutan in North Sumatra. Only some 800 animals survive in the wild, and all but none in captivity. Unfortunately for the species, its primary habitat, lying along the Batang Toru river to the south of Lake Toba, overlaps a lowland area that has also caught the eye of industry.

A large hydroelectrical project is planned right in the middle of the most important habitat for this highly threatened orangutan. But this is not an unsurmountable problem, according to government authorities.

A recent meeting in North Sumatra between the provincial office of the Nature Conservation Agency (BBKSDA), PT North Sumatera Hydro Energy (NSHE) and selected NGOs discussed how the threatened orangutans could be relocated.

Read also: Green economy becomes more concrete in Sumatra

Relocated? Where? Why?

The Batang Toru population, which was only discovered in 1997, has a very limited range. You cannot just take wild animals out of the forest and put them somewhere else. There is nowhere else. If you capture this population, you might as well shoot them in the process – the end result for orangutan conservation would be the same.

This is especially important because a group of scientists are now considering the Batang Toru orangutan as a new species of Sumatran orangutan. This is the most endangered species of great ape in the world, more endangered than Africa's mountain gorilla.

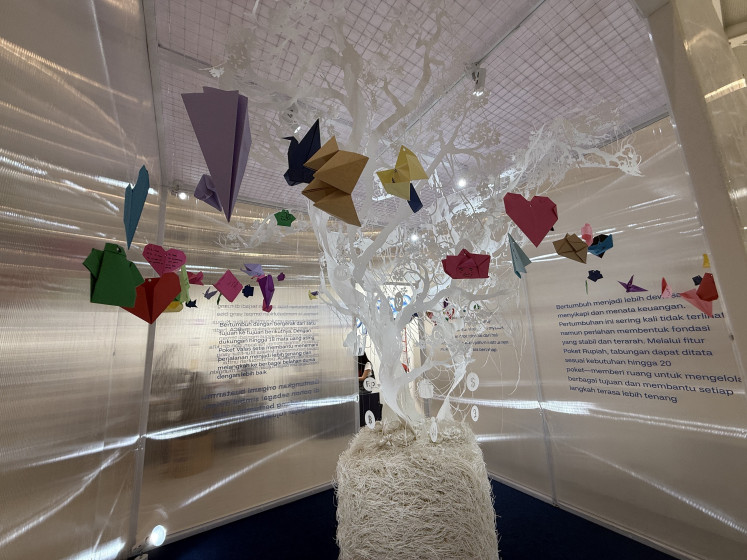

A large hydroelectrical project is planned right in the middle of the primary – and only – habitat for the Sumatran orangutan species that dwell in North Sumatra, along the Batang Toru river to the south of Lake Toba. (Matty Neikrug/Matty Neikrug)And why would the government relocate them? Orangutans are a fully protected species. This means, according to Law No. 5/1990, that “an individual is forbidden to catch, wound, kill, store, possess, smuggle or trade protected fauna, alive or dead”, as well as “take, damage, remove, trade, store or possess its eggs or nests”.

In short, you cannot harm a protected species or the place where it lives and breeds in any way. The only exceptions are when these protected species endanger human lives, or when studying them scientifically, under strict conditions.

Read also: Fantastic animals of Indonesia and where to find them

So why does the government think it can simply go and catch this critically endangered and legally protected species? Does the national conservation law not apply to the government? Surely these highly threatened Tapanuli orangutans are not endangering anyone. The state's conservation authorities should be doing everything in their power to save them and their remaining habitat, rather than trying to catch and move them.

A recent paper showed that despite decades of investing in conservation, the orangutan population in Kalimantan declined by 25 percent over the past 10 years. To put that into perspective, it would be similar to the human population in Indonesia losing 65 million people from 2007-2017. If orangutans were people, surely someone would have woken up and done something.

Orangutan conservation in Indonesia is not working. The government has had an action plan for 10 years now, but either the actions in that plan are not being implemented, or they are not effective.

Orangutans are mostly threatened by habitat loss – such as that being planned for Batang Toru – and their hunting for food, capturing as "pets" and killing as casualties of human conflicts. Saving orangutans requires protecting their habitat and stopping people from killing them, not pointless and dangerous translocations.

The current focus in orangutan conservation, however, is on rescue, rehabilitation and reintroduction. That’s where the money is. And money is what draws the eye of the media; that’s where political attention focuses.

But we cannot solve the orangutan crisis by capturing and relocating "problematic" orangutans – those that are in the way of the country’s development plans. Indonesian conservation authorities are not a cleaning service for badly managed development planning.

We need something much more constructive that fundamentally addresses the currently unsustainable way Indonesia’s natural resources are being used.

A healthy and prosperous Indonesia requires that its politicians protect its species, ecosystems and the vast benefits these provide to Indonesia’s citizens, as well as citizens of the world.

Editor's Note: The North Sumatera Conservation Agency has written a clarification letter in response to the article.

***

Dr. Erik Meijaard has worked as a conservation scientist and practitioner in Indonesia since 1992. He has extensively studied and commented on wildlife conservation in both Indonesian and Malaysian Borneo through the Borneo Futures initiative, an ongoing effort towards greater sustainability in natural resource use and improved wildlife conservation on the island. Erik is an Honorary Professor at the Center of Excellence for Environmental Decision at the University of Queensland and chairs the IUCN Oil Palm Task Force.

---------------

Interested in writing for thejakartapost.com? We are looking for information and opinions from experts in a variety of fields or others with appropriate writing skills. The content must be original on the following topics: lifestyle ( beauty, fashion, food ), entertainment, science & technology, health, parenting, social media, and sports. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com. Click here for more information.