Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFertility, blessings and protection cultures of baby slings

“Because God cannot be everywhere all the time, that’s why He created mothers” — Debra H. Yatim.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he significance of the baby carrier far transcends its practical use as a physical holder in which to cradle a baby. Several cultures differ in how they see woven carriers, from the maternal philosophy behind them to the patterns that grace the fabrics.

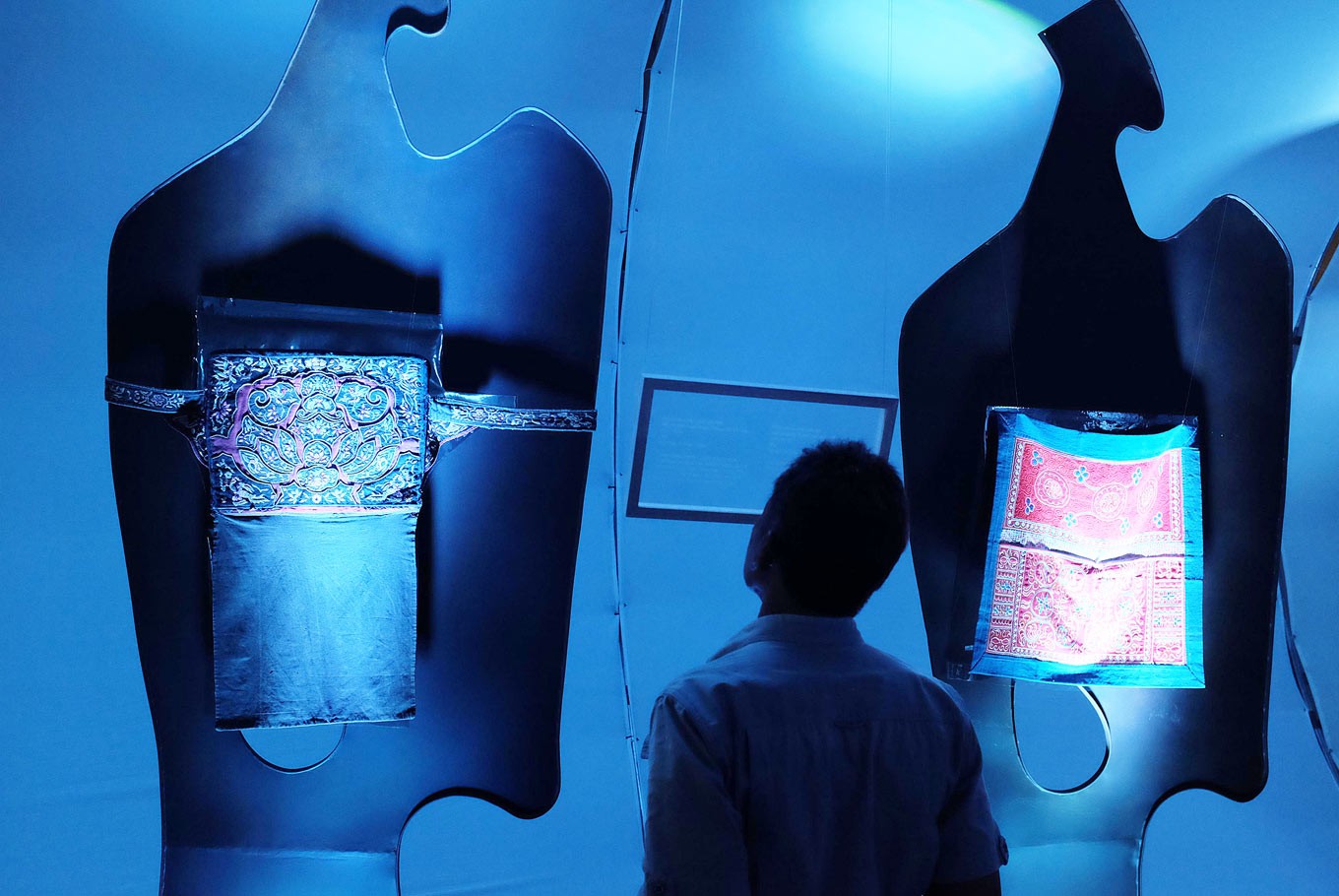

The “Fertil, Barakat, Ayom-Budaya Gendongan Bayi (Fertility, Blessing and Protection — Culture of Baby Slings)” exhibition at the National Museum, which runs until Oct. 29, is a joint project involving the National Museum of Prehistory in Taiwan (NMPT) as well as the National Museum and art collective Studiohanafi.

Its visit to Jakarta is part of an international tour of items from the museum, after previously being showcased in Taiwan and New York City.

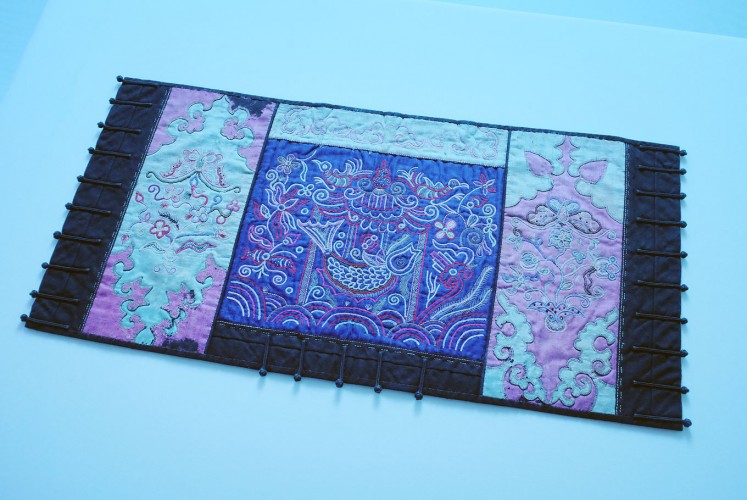

Up to 27 “baby cradle” artifacts from the NMPT are showcased, coupled with several related artifacts from the National Museum itself. The baby carriers exhibited are filled with multiple interpretations based on their patterns, designs and their cultural and historical backgrounds.

Many of the artifacts brought from Taiwan are woven child cradles from the southeast of China, where NMPT curator Chi Shan-Shang explains people are very particular and elaborate when designing their baby’s cradles because of the high regard for ancestors and their religious beliefs.

Butterflies, spiders and rhododendron flowers are recurring but distinct patterns in most of the cradles in the collection, all of which have a maternal symbolism to them.

Aside from the Chinese artifacts, the Indonesian artifacts also provide an exploration of the child-cradling habits of some Indonesian cultures giving an interesting insight into how they view the relationship between infants and their parents, as well as the environment around them and the spiritual meaning behind how cultures raise their young.

Anthropologist Tony Rudyanshah made an observation particularly on the child-raising habits of the Balinese culture, seeing that children are usually present or even involved in cultural activities such as dance and music if their parents are involved as well.

Balinese men, he said, tend to bring their children along while they practice gamelan, exposing their infants to the sound and atmosphere from the beginning.

He notes that how the child is reared and brought up by the parents will significantly shape the child’s character, sensitivity and well-being, which includes how the child is carried in its cradle during infancy.

In some cultures, the way that they perceive life and death will also affect the way they hold a baby.

“The Balinese believe that a newborn baby is a noble and holy creature, above the ground that we walk. That’s why they have a special ritual for every newborn 105 days after their birth. After the ritual, the baby’s feet are then allowed to touch the ground. Cradling the child therefore also fulfills a spiritual need,” he explained.

Up close: The baby slings on display feature several interpretations based on their pattern, design and cultural and historical background. (JP/Jerry Adiguna)Other rural cultures in Indonesia, such as the Kenyah tribe of East Kalimantan (and partially Sarawak in Malaysia), see the baby’s cradle as a vessel or a container that keeps the baby’s soul at bay. The way the cradles in the Kenyah tribe are designed is based on their philosophy of “Ba,” explains fellow anthropologist Dave Lumenta.

Since the Kenyah believe that an infant’s soul behaves in an otherworldly manner, the cradles are designed to spiritually and physically keep the child close to their bearers. Coupled by the fact that the Kenyah are a nomadic tribe, meaning that they migrate between their cultural lands, keeping a child close at hand is considered essential.

“‘Ba’ itself is the bond between the adult and the baby […] a spiritual umbilical cord basically. Its function is to tether the child’s soul close to the parents’ bodies so that the child’s soul will not wander too far off,” Dave explains.

“Tribes in this area of Kalimantan tend to make basket-shaped cradles, using rattan wood, and this is placed on their parents’ body with their feet always on or in the direction of their hips.” Dave explains.

By going on tour, the exhibition is seen by Chi as a kind of umbilical cord beginning from Taiwan and stretching itself around the world, in an attempt to bridge understanding and interaction between cultures and end up bringing out “humanity’s universal values” through the relationship between child and parent.

“For one, the Dong tribe of Southern China see the spider as a symbol for a mother. That is why their patterns occur a lot on the cradles: It underlines the importance of a mother in raising their child, physically and spiritually,” Chi says.

The Fertil, Barakat, Ayom-Budaya Gendongan Bayi (Fertility, Blessing and Protection — Culture of Baby Slings) exhibition at the National Museum, which runs until Oct. 29, is a joint project involving the National Museum of Prehistory in Taiwan (NMPT) as well as the National Museum and art collective Studiohanafi. (JP/Jerry Adiguna)