Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFendry Ekel: Discovering all the other truths around

In any case, we have to be ready to enter the space to view Fendry’s art pieces and face some truths.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n order to view the works in Fendry Ekel’s ongoing exhibition at the Erasmus Huis in Jakarta, appropriately entitled “Entries,” viewers have to pass through an iron threshold.

Although actually quite different in form to those who have visited Auschwitz-Birkenau, its curvilinear shape is somewhat reminiscent of the curves of the ironwork above the gate of the notorious Nazi concentration camp.

The words placed above the gate read “Im Anfang war das Wort” (In the beginning there was the word), an excerpt from the Bible (John 1:1), instead of the ironic “Arbeit macht frei” (Work sets you free) of Auschwitz.

In any case, we have to be ready to enter the space to view Fendry’s art pieces and face some truths.

An entrance to Fendry Ekel's exhibition at Erasmus Huis, Jakarta. The words placed above the gate read “Im Anfang war das Wort” (In the beginning there was the word), an excerpt from the Bible (John 1:1), instead of the ironic “Arbeit macht frei” (Work sets you free) of Auschwitz. (Erasmus Huis and Fendry Ekel/File)While at a glance the artworks may seem to be simple depictions of ordinary objects or important personalities, they are usually more than just a mere representation. Layers of meaning can be discovered in each painting.

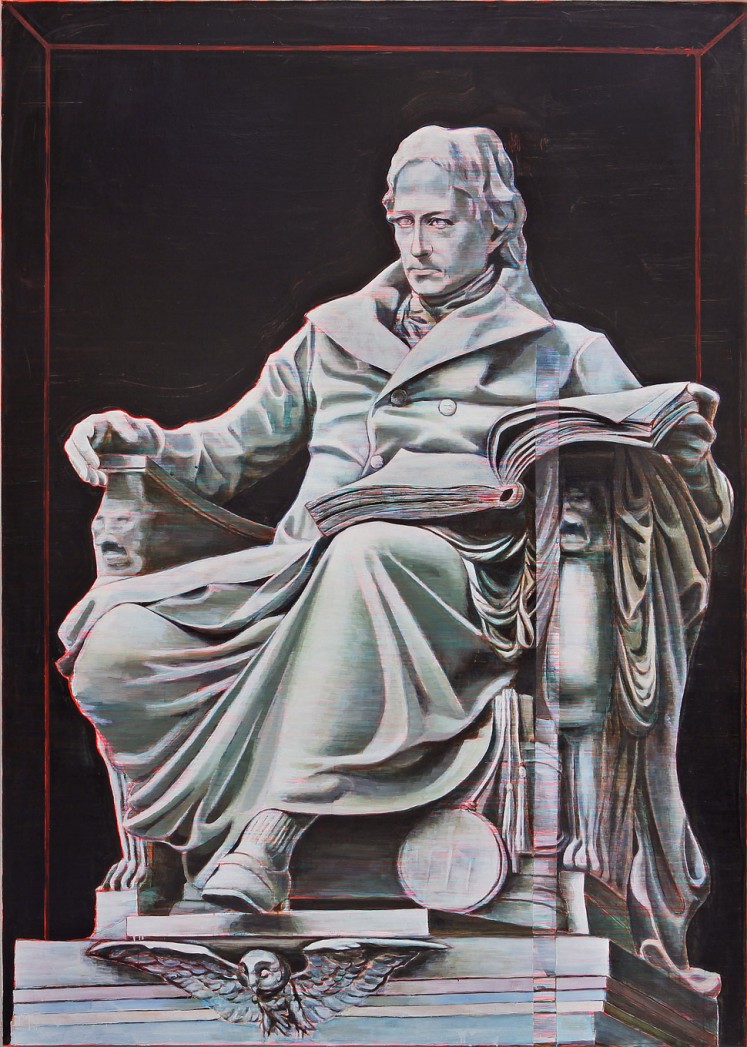

Investigation #7 is Fendry’s painting of a photograph of a monument depicting Wilhelm von Humboldt, the founder of Humboldt University of Berlin.

For years, the monument served as a convenient meeting point for him and his friends, but interestingly, Humboldt apparently was a noted scholar of the Kawi language, an archaic form of Javanese, and that academic relationship with Indonesia gave the monument an even more special meaning to the artist.

Fendry starts with files of images he wants to present, and deliberates upon exactly which image to use.

Sometimes his deliberations can take quite a long time — months or even years. Once the images are transferred to the canvas, he writes notes of his ideas directly onto that same canvas. Later he mostly covers up the notes with layers of paint, but leaves small traces of them.

Investigation #7 by Fendry Ekel (Erasmus Huis and Fendry Ekel/File)Although most of the exhibited artwork may seem black and white, they are usually composed of many different colors; the color mixing processes reduce the colors to almost total black and white.

Some paintings are more colorful. Greta Garbo as Mata Hari certainly comes from the 1931 movie about the Dutch exotic dancer who secretly moonlights as a spy for the Germans. However, the image that Fendry chose to depict does not appear in the movie itself. Fendry carefully chose an image that was specially photographed in relation to the promotion of the film, not a still from the movie set. Context is very important to the artist.

[gal:3]

Through Witness #6, a depiction of a cockatoo, Fendry discusses how hoaxes emerge in our social media society.

Of course, sometimes a hoax is deliberately manufactured and spread, but more often than people realize, hoaxes are spread via our ignorance.

Like a cockatoo merely parroting words, we often pass on old information, taken out of context, to the current environment, making it seem like real news. A simple painting of a silly old bird becomes a reminder that we have to always understand the context of the information we obtain.

[gal:4]

Labels are almost always absent from the exhibition. There were no explanations of the pieces. Only lists of the artwork titles and their information were viewable at two or three strategic spots around the exhibition area, but not beside the artworks themselves.

A mirror also appears as part of the exhibition. “Art is the mirror of the soul,” said Michael Rauner, Erasmus Huis director.

If we are not able to see Fendry’s soul just yet, perhaps we can use his art to reflect on our own soul.

Some other works show only numbers: 1998 and 1987. What do they represent? They clearly indicate a year. What might 1998 mean for the artist? If we do not know that yet, we can also ask, what does 1998 mean for us?

Chinese-Indonesians, like me, would associate 1998 with the ethnic riots that happened that year. For me personally, that is also the year my daughter was born. Surely the year signifies something different for every viewer. The year 1987 was the year Fendry, who was born and raised in Indonesia, moved to Holland.

For Fendry, the exhibition is not about “coming back home,” but rather he sees himself on a constant journey. Similarly, he uses mirrors not only to view himself, but to see what is around him, as one would use a rearview mirror in a car.

While we can learn more about ourselves or about Fendry Ekel through his artwork in the exhibition, which runs until March 16, they can also become a means for us to know more about many things around us.

Some might want to know more about Humboldt’s interest in the Kawi language, while others might be interested in Margaretha Geertruida MacLeod, the spy better known as Mata Hari. Hopefully, the art can help us enter worlds of truth around us.