Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe mind-numbing greatness of Pramoedya Ananta Toer

An exhibition celebrating the life of Indonesia’s most-venerated writer, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, is a love letter not only to the man but his readers and family as well.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n 2006, moments before he passed away, great Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer asked his children to put some money in a kangaroo pouch. He wanted to give some of that money to whoever was begging on his walk.

“Even when there was a neighbor asking him for his watch, he’d give it,” his daughter, Astuti Ananta Toer or Titiek, told The Jakarta Post.

Pramoedya did not need to subject himself to that kind of empathy. But empathy was all he had — he wasn’t rich; being a celebrity never crossed his mind.

His empathy also put him in the pantheon of some of the most-venerated figures of Indonesian literature — his books, such as the breathtaking Perburuan (The Fugitive) or the sprawling Buru tetralogy, have irrevocably become its face. It was also what led him to multiple prisons: in Cipinang, in Bukit Duri, on Buru Island, his own house. Because of it, he saw his house ransacked, his belongings taken away.

Pramoedya’s life and work were on display at the gallery Dia.Lo.Gue in Kemang, South Jakarta. Until May 20, the exhibition, titled Namaku Pram: Catatan dan Arsip (My Name Is Pram: Notes and Archive) his face — both nurtured by a bright future and ravaged by a grave past — will appear on a wall chronicling his life.

Read also: Exhibition reveals rare glimpse of literary legend Pramoedya Ananta Toer

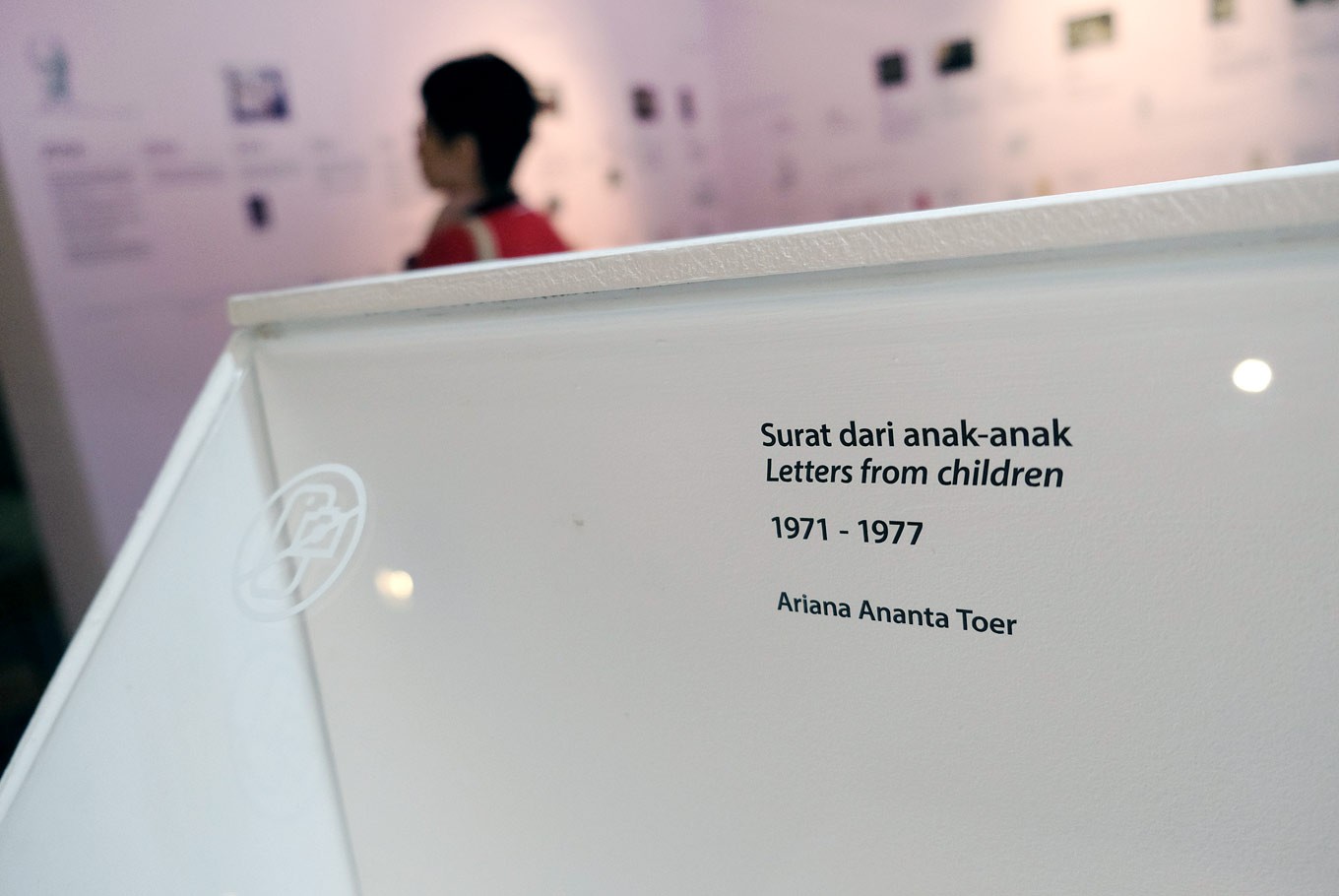

Papers containing his words, be them in the form of letters sent to his family or first-edition copies of his books, are encased in glass boxes for visitors to see, to remember. One of the rooms on display contains Pram’s desk, complete with a typewriter and a mock Djarum cigarette pack.

The exhibition was the product of admiration. Actress Happy Salma, through her Titimangsa Foundation, mounted a play based on Pramoedya’s once-banned novels Bumi Manusia (The Earth of Mankind) and Anak Semua Bangsa(Child of All Nations) called Bunga Penutup Abad (The Flower That Ends a Century).

In 2016 and 2017, Happy and Dia.Lo.Gue’s owner Engel Tanzil worked on the display by meeting with Pramoedya’s estate and collecting his archives.

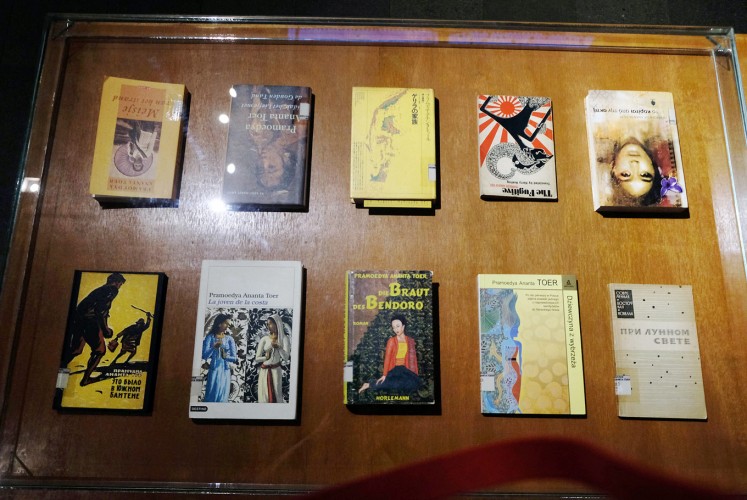

World-renowned: A collection of Pramoedya's books that have been translated. (JP/Jerry Adiguna)“He was the best documentarian Indonesia has ever seen,” Happy said during the gathering at Dia.Lo.Gue. A smaller scale of the exhibition is also being held at Galeri Indonesia Kaya, Jakarta, until May 2.

The gathering featured a performance by Pramoedya’s grandchildren and ended with a ceremonial tumpengan procession and the handing out of Pram’s books to those involved with the exhibition.

A diarist since childhood, Pramoedya was born on Feb. 6, 1925 in Blora, Central Java. According to Titiek, his upbringing was what led Pramoedya to pass no judgment on people living under the dark clouds of discrimination: from women to beggars he gave money to.

In 1960, he published the book Hoakiau di Indonesia (Overseas Chinese in Indonesia) — an extensive, sympathetic non-fiction work detailing the plight of Chinese-Indonesians. His reward? A stay at Cipinang prison.

He’s been recognized by the likes of the association of writers called PEN International. In 1988, he was awarded the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award for the book Rumah Kaca (The Glass House, the fourth entry in the Buru tetralogy).

Perburuan also received an award from Balai Pustaka. He was the closest person Indonesia had to a Nobel laureate in literature. Conversely, he’s also remembered for his lost manuscripts, such as his first novel Sepuluh KepalaNICA (NICA’s Ten Heads) or Ditepi Kali Bekasi (On the Edge of the Bekasi River).

Touring the exhibition — which also screens a video of several testimonials, including from Titiek — these accolades seemed to be an afterthought. What felt moving was the intimate portrait of a man whose image is still being shaped to this day.

Though conceding that the exhibition is the best one that she’s seen so far, pain lingers in Titiek. “Being reminded of Pram is like having your heart cut up to pieces. It was like seeing his face all over again,” she said. Living her life oscillating between pain and relief — when her father was taken, when her father came back — might have crowded her head.

Speaking to reporters to mark the opening on April 16, Pram's daughter, Astuti Ananta Toer, said the family together with organizers had carefully curated manuscripts of his works as well as personal letters written by him. (Galeri Indonesia Kaya/File)“Pram was an individualist. He never believed in organizations,” Titiek said, when asked her what the biggest misconception we have of him was. “He also never stopped working. His books were like his spiritual children.” Pramoedya was also linked to organizations such as the now-defunct leftist artists association Lekra and the People’s Democratic Party.

There is a passion project by Pramoedya that has yet to see the light of the day: two expansive, incomplete encyclopedias called Ensiklopedia Geografi Indonesia (Enclycopedia of Indonesia’s Geography) and Ensiklopedi Citrawi Indonesia (Encyclopedia of Indonesia’s Image) of Indonesia’s history and cultures (some parts of it were snatched from under him by the government). His family still owns and has been approached by publishers, but they have yet to agree for a release.

Forever etched in Indonesia’s history, what we have now is his books and his memories. What he saw then is what we could see now — and all we need to do is turn a page.