Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

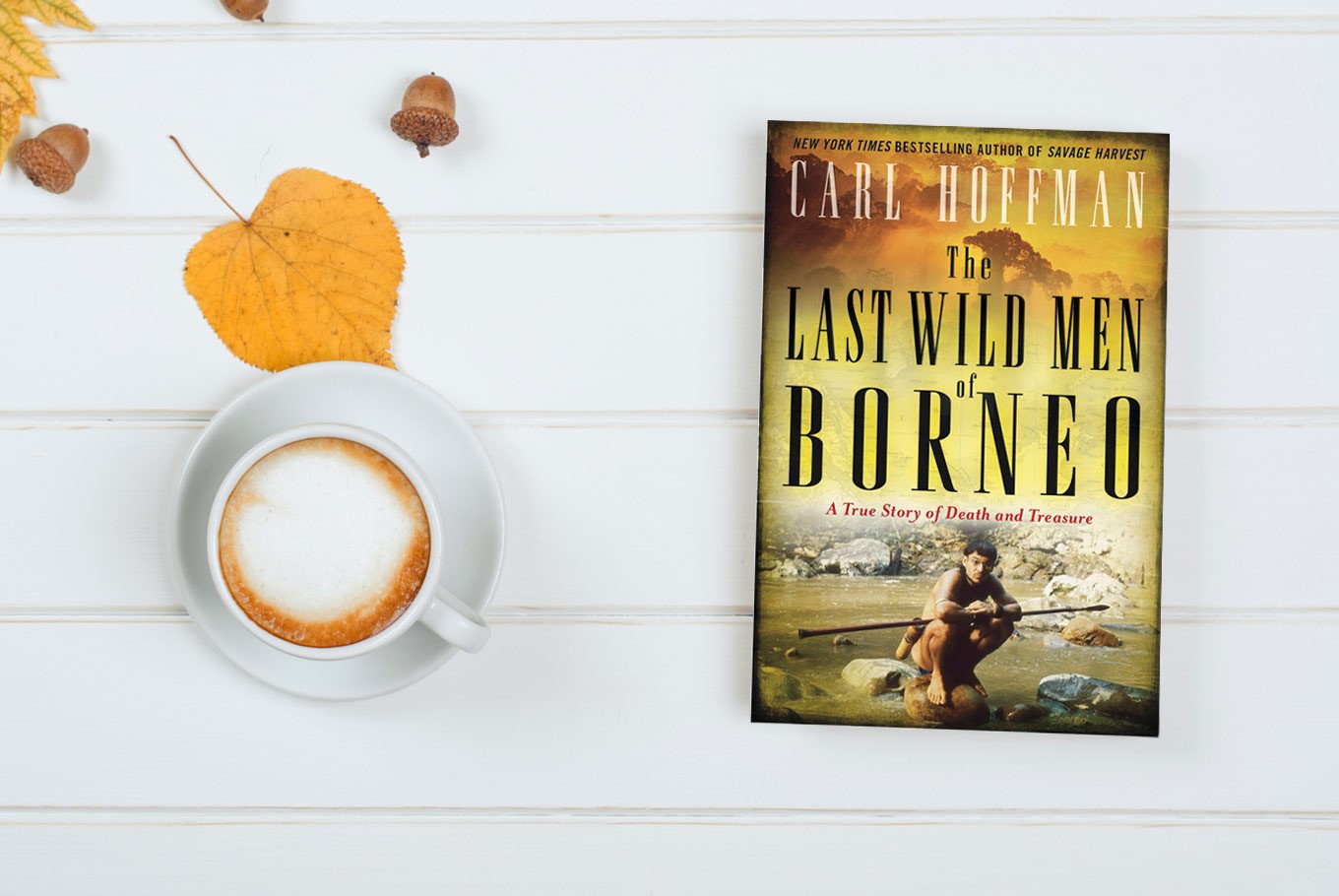

View all search resultsBook Review: 'The Last Wild Men of Borneo' by Carl Hoffman

Carl Hoffman’s latest book The Last Wild Men of Borneo is touted as “a true story of death and treasure”.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n The Last Wild Men of Borneo, Carl Hoffman chronicles the lives of two very different foreigners and their very different relationships with Borneo, that great island Indonesia shares with Malaysia and the tiny state of Brunei Darussalam.

Bruno Manser was a Swiss national who found his way to the jungles of Malaysian Borneo in the 1980s, in search of a purer, more primitive way of living. He found what he was looking for among the nomadic Penan, ultimately dedicating his life to saving their rainforest and the traditional way of life that depended on it.

Hoffman’s second protagonist, Michael Palmieri, lives in Bali among his collection of Dayak artefacts; ancient carved ironwood statues, reliquaries, weavings, and powerful bear-tooth necklaces imbued with magic.

A dashing young man who pioneered the trade in Borneo’s tribal art in the eighties, Michael is now comfortably ensconced in his “grass hut” in Bali; happy to reminisce and revisit some of his old haunts for Hoffman’s book.

The story moves back and forth, chapter by chapter, between the lives of these two men. The one driven by ideology and purity, a seeker of truth; the other by business and beauty, a seeker of treasure. The one an ascetic, the other a modern-day buccaneer; both of them drawn and inextricably bound to the island of Borneo and its indigenous peoples.

While the parallels and links between the two are sometimes a little stretched, the juxtaposition of the two characters works, and the narrative is compelling: Both stories are well worth telling, and both are well told.

Hoffman has a journalist’s nose for a good story and he writes with an assuredness that makes for a good read. This is a tale of high adventure, of exotic lands, risky escapades, narrow escapes, and rich rewards.

Manser is easily characterized as a real-life Tarzan, trekking alone in the jungle, climbing mountains, fording rapids and wrestling pythons. But all of this is founded in truth: In real life, Manser became a hero to many, both in the Penan lands of central Borneo, and in the West, where an environmental ethic was taking hold.

In Hoffman’s story, Palmieri becomes another kind of hero, a swashbuckling American larrikin, smuggling contraband for Afghan princes, exploring steamy jungles in search of Dayak booty, wheeling and dealing in the dodgy backstreets of Samarinda and Kuching.

Both characters have their ways with women, but neither, in the end, is portrayed as a complete man. And one is left wondering how much of the portrayal is real and how much is showmanship, yarn spinning, storytelling.

The Last Wild Men of Borneo, published in March this year, follows a tradition of adventurous travel tales set in Borneo; among others, Redmond O’Hanlon’s Into the Heart of Borneo ( 1984 ), Eric Hanson’s A Stranger in the Forest, on foot across Borneo ( 1988 ), and my own Crazy Little Heaven, an Indonesian Journey ( 2013 ).

What these books have in common is that they are all tales of white men in a dark land. “Boys own” adventures, ripping yarns that echo the romantic fantasies of a long-gone colonial era. In all of these tales, the line between fact and fantasy blurs a little at the edges: tribal magic, powerful talisman, and post-colonial fantasies create a potent mix.

On one level, Hoffman is exploring the genre, playing with it, stirring the pot and consciously replaying those colonial myths. At times he addresses the issue head on, teasing out the lives of the two men, asking the questions about what motivates them, about the ethics of their actions. On another level, Hoffman is living it. Making real the fantasy of a white man alone in the jungle.

Perhaps the most compelling passages of the book are in the final chapters, when the writer describes his own ventures into Penan territory, where he confronts his own myths and realities in what remains of their forest.

Running deep throughout the narrative is the tangled thread of an ethical drama. Like Leakey’s angels, Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas in Borneo, Manser becomes a warrior, waging a David-and-Goliath war on the corrupt and powerful Malaysian government and its crony timber barons.

Another western trope, the lone white man, rallying the natives, standing up to the might of the rich and powerful; a White Rajah, a Lawrence of Arabia, the Last Samurai. While the ethics of forest and cultural preservation seem clear, is it right, as Prime Minister Mahathir asks in a letter to Manser, to hold the Penan back, to stand in the way of development?

Is Palmieri a defender of the Dayak? Saving their material culture before it is lost to loggers, palm oil fires, and unscrupulous art dealers? Rescuing ancient treasures from the rotting jungle, and placing them on display in the museums of New York and Paris: Is this preservation or is it cultural appropriation?

Is Palmieri the last of a long line of westerners looting the treasures of the orient, an Indiana Jones feeding the West’s hunger for lost myth and meaning; for nostalgic yearnings for a mythical colonial era?

And is Hoffman feeding this western fantasy, this appetite for exoticism? Or is he exploring the political and moral dimensions of that fantasy through the lives of these two men?

The Last Wild Men of Borneo dances deftly around these issues, exploring the psychological, cultural and ethical through the real-life adventures of its two heroes. But ultimately there is no answer. Or perhaps the answer is that we are all actors in this drama, there are no clear rights and wrongs, only the lives of individuals, the movements of societies.

Manser never went home, after years spent between the mountains of Switzerland and his spiritual home in Borneo, he chose to end it there in the Penan jungles. His death remains a mystery, his body never found.

Palmieri is still in Bali, having left the United States to avoid the draft as a young man, he too has found his spiritual home on the other side of the planet.

Perhaps Hoffman, who is also the author of critically acclaimed Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest and The Lunatic Express, is exploring his own impulses and drives in this book?

I think of my own life, of twenty-five years in Indonesia, of the pull of my homeland in Tasmania and the counter-pull of this nation of islands and cultures. A dynamic that I explored in my own book. I think, too, of others; friends who never went home, escapees from the conventional western world of the sixties who, having escaped, found a new life here in the East — and now lie buried in its fecund earth.