Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTrilateral fact-checking talk shares tips on stemming COVID-19 infodemic

Three expert panelists from Indonesia, India and Nepal took part in a virtual discussion to share their tips on how news consumers can do their part in stemming the COVID-19 infodemic.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

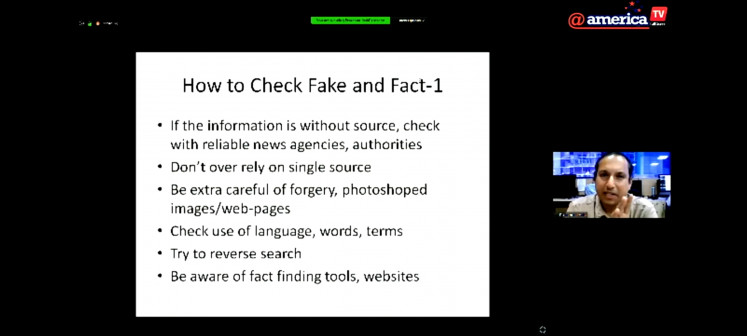

to Anyone

Check before you share: REDAXI co-founder Rut Rismanta Silalahi (inset) presents a slideshow during an International Fact-Checking Day discussion on April 2, 2020, hosted virtually by @america Jakarta. The COVID-19 infodemic is spreading as fast as – if not faster – than the virus that causes the disease. (www.youtube.com/user/atamericaa/-)

Check before you share: REDAXI co-founder Rut Rismanta Silalahi (inset) presents a slideshow during an International Fact-Checking Day discussion on April 2, 2020, hosted virtually by @america Jakarta. The COVID-19 infodemic is spreading as fast as – if not faster – than the virus that causes the disease. (www.youtube.com/user/atamericaa/-)

P

otential cures or preventive remedies for COVID-19 have become the most consumed and shared information on social media during the current health crisis, no matter how obviously unreliable they might be.

In Indonesia, for example, a viral video purported to be from a TV interview suggested to a toddler that eating boiled eggs before midnight could "make people immune" to COVID-19.

It was a poorly doctored video, and viewers could clearly see that an adult's mouth had been superimposed on the child's face, but apparently, many people actually believed it and started following the suggestion.

Co-founder Rut Rismanta Silalahi of REDAXI, which provides digital literacy education, said that posts claiming cures for COVID-19 was the most fact-checked information at present.

“The three top fact-checked information [...] are information on politics, racism, and health,” she said on April 2 during a live-streamed discussion to mark International Fact-Checking Day.

“We don’t have the data yet, but I believe that the most fact-checked information during this period are [COVID-19] cures. Because people are waiting in uncertainty, producers of fake news are using [the situation] to spread misinformation on cures and effective ways of boosting immunity,” Rut added.

The International Fact-Checking Day discussion, organized by @america in Jakarta, was moderated by director of student affairs Devie Rahmawati of the University of Indonesia with an introduction by the US Embassy's regional public engagement specialist, Scott E. Hartmann. It was held to "learn how fact-checkers from Indo-Pacific countries – Indonesia, India, and Nepal – are seeking truth and combating fake news" according to @america, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prasanna Joshi, senior producer and anchor of ABP Majha, a TV news channel in Maharashtra, India, said that news consumers these days were most concerned about three keywords or phrases.

Fact-checking 101: Senior producer and anchor Prasanna Joshi (inset) of 'TV news channel ABP Majha' in Maharashtra, India, provides basic steps on how to sort fact from fiction during a virtual discussion to mark International Fact-Checking Day on April 2, 2020. (www.youtube.com/user/atamerica/-)He said the first was “lockdown”, as the public needed certainty regarding the period of restrictions on their movement, whether it would be prolonged to the summer school holiday.

The second was “spread of the virus”, as some information had emerged that the COVID-19 virus had become airborne or was spreading through pets and poultry products, or through Chinese goods.

“And then it's 'cure' or 'vaccine'. In Maharashtra, where I live, somebody raised the issue that you need to drink black coffee with some spices added – not only that, you need to drink it at the stroke of midnight – and it will cure you or at least it will protect you from [the] coronavirus. People actually did it. It’s happening here,” said Joshi.

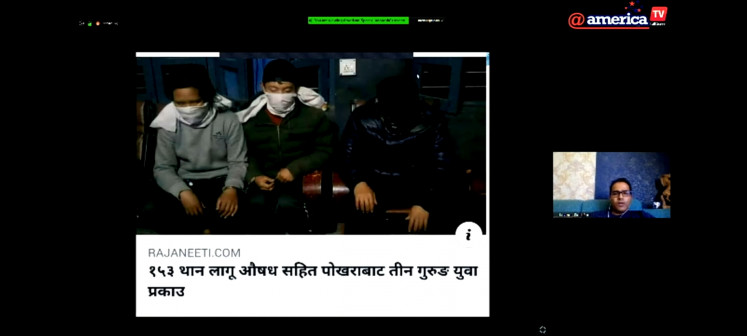

Laxman Datt Pant, who chairs the non-governmental advocacy group Media Action Nepal (MAN) and is senior special correspondent of TV Today in Kathmandu, also shared stories of how misleading news headlines and unverified videos were being shared on social media with little effort from consumers on checking the facts.

Like wildfire: Media Action Nepal (MAN) chair Laxman Datt Pant (inset), who is also senior special correspondent of Kathmandu's 'TV Today', presents examples of fake news and hoaxes during the online International Fact-Checking Day discussion hosted by @america Jakarta on April 2, 2020. (www.youtube.com/user/atamerica/-)He said that MAN had recorded 110 news with fake content – including those on COVID-19 – that had been published in 11 daily newspapers, and 50 fake news published on 10 online news portals.

“A reputed news portal claimed in its headline that about 500 million Indians would be infected by the COVID-19 [virus] by the end of July this year that cited an opinion article from The New York Times, and that [headline] caused fear among Nepalis,” said Pant.

The two foreign panelists said that authorities in India and Nepal had acknowledged the difficulties in stemming the COVID-19 infodemic – a portmanteau combining "information" and "pandemic" coined by political scientist David J. Rothkopf during the 2003 SARS endemic.

“The government and the Supreme Court of India have expressed their concerns. The government has officially said, ‘We can contain the virus, but we cannot contain the fake news’,” said Joshi.

All three panelists pointed out that news consumers had a role to play, both in spreading and curbing the COVID-19 infodemic.

Joshi said that the infodemic involved misinformation or the more harmful disinformation, as well as mal-information, all of which people might consume easily because they confirmed people’s beliefs or biases, or because the information was presented in a manner that only a trained person would recognize as contrived.

“The rule of thumb is, if it is too good to be true, then it [is likely to] be too good to be true,” he said. Joshi stressed that people should refrain from forwarding information before verifying the news source as well as the content.

Meanwhile, Rut pointed out that scolding family members publicly in a chat group for forwarding unverified content was culturally unacceptable. She added, however, that there were ways to provide other information in a polite way to debunk a previous message or post.

“We need to do our part, even though you might not be a professional fact-checker or journalist. You can learn more about fake information and how to combat it,” she said.