Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBorn in a concentration camp: The Holocaust's youngest survivors

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

olocaust survivor Florence Schulmann has always worried that if she went into schools to recount her experience, it would sound almost fantastical: "I'd be too scared that they wouldn't believe me."

It is the first time that the retired French shopkeeper, now living in Paris's 11th district, has shared her story under her real name.

"My mother brought me into the world next to a heap of bodies," she says.

AFP spoke to her and two other Holocaust survivors who share the same, seldom discussed experience: they were born in Nazi concentration camps.

Unlike Schulmann, Hana Berger Moran has no apprehensions about visiting schools to tell her story.

A gentle-natured, yet dynamic woman, whose plum-colored glasses dominate her face, Berger Moran now lives in the Californian town of Orinda after a career working in the quality department of a cutting-edge biotechnology company.

But her birth certificate is on display at the memorial for the Mauthausen concentration camp in northern Austria, where her birth was registered.

Also in the United States, Mark Olsky has the build of an ex-American football player and lives near Chicago after a career as a casualty department doctor.

He was delivered between April 18 and 21 -- he'll never know the exact date -- in a cattle truck taking deportees to Mauthausen.

All three were born in 1945; Schulmann on March 24 in Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany, and Berger Moran on April 12 in the Freiberg subcamp in eastern Germany.

All of their mothers were deported while pregnant, from Poland in the case of Schulmann and Olsky, and from Czechoslovakia in Berger Moran's case.

Infants when the camps were liberated, the three 75-year-olds will no doubt be among the last able to bear witness to the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust, which claimed the lives of six million Jews.

Twenty years younger than most survivors, all of them have a different relationship to the circumstances of their birth.

But all three share the same serious, intelligent outlook, born out of the most extreme adversity.

Saved by fortuity

The fact that they survived was largely down to timing, as World War II entered its final phase.

Since summer 1944, Soviet troops had been advancing from the east and liberated the camps one by one.

The Red Army reached Auschwitz in January 1945.

Panic and disorder then spread through the other camps as the Nazi leadership began fearing the aftermath of defeat and some guards behaved in ways they likely would not have done just months or weeks earlier.

Berger Moran says that when the camp wardens realized her mother was about to give birth, they brought her a basin full of hot water.

"And there were people standing around because it was in a factory, on a table and there was a paediatrician from Prague who helped my mother to deliver me," she says, a discreet string of pearls and a scarf around her neck.

Two days after she was born, Berger Moran and her mother were put on a train to Mauthausen, where her birth was registered.

The Germans crammed more than 2,000 women into that train, hoping that once they were transported to the last camps in operation, they could be murdered without leaving a trace.

Deportation survivor Florence Schulmann, born in 1945 at the Bergen-Belsen camp poses in Paris on January 23, 2020. (AFP/Lionel Bonaventure)The train took more than two weeks, travelling between April 14 and 29.

Some of the deportees gave birth piled on top of the others in the carriage.

One stationmaster later described to historians his horror at the hellish sight of skeletal pregnant women among the passengers.

He supplied clothes for three newborn babies and food for their mothers.

Among those newborn babies was Mark Olsky.

His mother didn't know precisely when he was born so on arrival at Mauthausen, he says she attempted to move the guards by telling them he arrived on April 20 -- Hitler's birthday.

When Schulmann's mother went into labour at Bergen-Belsen, she dared to ask a female guard for a blanket as her waters began breaking.

"She said to herself that she was going to get a bullet in the head and then it would all be over," says Schulmann.

"But this woman calmly opened her bag and gave her a packet of cigarettes. She said that with that, she could get whatever she wanted in the camp."

When the Allies liberated Mauthausen and Bergen-Belsen, among the shocking discoveries they made was the presence of scrawny infants wrapped in newspaper, with their equally malnourished mothers trying to nurse them.

Schulmann, Berger Moran, Olsky and the other infants like them were held up as moving symbols of victory over the evil of Nazism.

Read also: Germany marks Holocaust anniversary in shadow of virus

'I was ashamed'

After surviving birth in such inhuman circumstances, those same infants had to face the challenge later in life of how to process what happened to them and their families.

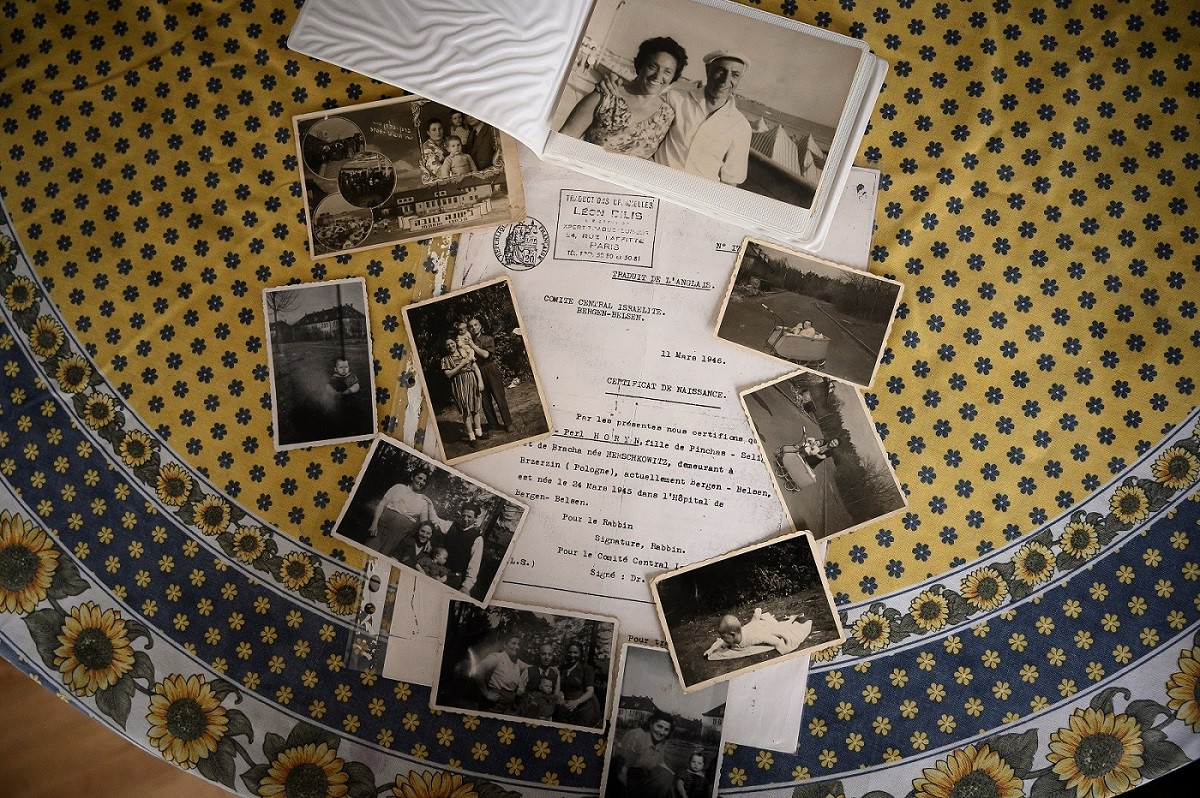

"All my life, day and night, I have lived with the Shoah," says Schulmann, her back hunched as she rifles through a box full of photos and documents.

She describes a dour childhood.

"The mood was very sombre at home, my parents would brood," she says.

"They kept me in a cocoon -- as soon as I had a cough, they would take me to the doctor."

Before being deported to the camps, Schulmann's parents were in one of the ghettos in Poland.

Their first son was taken from them at the age of just three and murdered in the gas chambers.

"My childhood was suffocating, I was ashamed," she says.

"I would get asked: 'What did your mother do to ensure you survived?'," she remembers, Israel's international i24 news TV channel, which broadcasts in French, on in the background.

As an adolescent, she visited a friend of her mother's in Tel Aviv.

"This woman opened the window and gathered the whole neighborhood," she says, recalling the queue of visitors all the way up to the fourth floor where the woman lived.

"They were coming to touch the miracle survivor."

Schulmann and Berger Moran feel the circumstances of their birth weighed heavily on them growing up, while Olsky says that, for a long time, he thought his was a "unique experience".

Infamous experiments

Some pregnant women in the camps later recounted how they had had to sign a form authorising the Nazis to kill their child after birth, according to anthropologist Staci Jill Rosenthal, who has carried out rare research into the topic.

"The research is still rudimentary," Diana Gring, curator of testimonies at the Bergen-Belsen foundation, says.

Around 200 births were recorded at Bergen-Belsen alone, but, according to Gring, the destruction of certain records and the disappearance of bodies means "we don't know how many children were born in the camps".

Journalist Alwin Meyer, who wrote a book about babies born in Auschwitz, thinks the number is in the thousands.

There are also published testimonies from two midwives in the camps who described how they sought -- most often in vain -- to prevent various forms of violence against newborn children, including murder.

Some of the babies who matched the Nazis' "Aryan" physical criteria were taken from the camps and adopted by German families.

Others were swapped for German prisoners of war in the West or in neutral countries.

But most died, many in horrible conditions.

Some were subjected to the experiments carried out by the infamous doctor Josef Mengele.

One new mother had her breasts strapped to see how long her newborn daughter would survive without milk.

Mengele came every day to witness the agony.

'Laughter is the best revenge'

"My parents came out of that darkness completely traumatized, they never talked about the war," says Schulmann.

Berger Moran's mother only spoke about the past rarely and the fact that they moved back to Czechoslovakia after the war made discussing it even more difficult.

"It was a Communist country you know, you didn’t talk about those things!"

As an adult in the 1960s, Berger Moran emigrated to Israel and then on to the United States.

Olsky went to Munich, then followed the same route to Israel in 1959 and eventually the US.

His mother had lost her husband in the camp.

But she sought to shield him from what she had gone through, seeing to it "that I would grow up with as little fear and worry" as possible, Olsky says.

So how does one go about building a joyful life from such beginnings?

Berger Moran recalls an audience member at one event who asked her: How can you laugh?, to which she replied: "What else is there?"

"I said: 'It's the best revenge that I can laugh, that I can have fun.'"

But they are conscious that anti-Jewish hatred is once again on the rise in the US and in Europe, with the wearing of a kippa becoming a potentially risky act in some places.

Olsky says the climate in the US and elsewhere in the world has disturbing parallels with the 1930s and that there is a danger of complacency.

Many people may "suddenly find out that what they took for granted as being an adequate level of safety, turns out to be no safety at all," he says.

'Will people remember?'

According to a survey by the Schoen Consulting company published in January, 69 percent of French people under the age of 38 don't know the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust.

Speaking at an event to mark the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz earlier this year, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin called for reflection on the question of "how to pass on Holocaust remembrance to generations who will live in a world without survivors".

"An audience will perceive events more strongly if the narrator has lived through them," says Bernhard Muehleder, one of the team at the Mauthausen memorial who work on producing educational resources.

To that end, the "babies of the camps" have committed their stories to video.

Even Schulmann recently decided to take this step, "so that my story won't be disputed by historians," she says.

But she says that talking about what happened with her daughter and grandchildren is still difficult.

After a visit to Bergen-Belsen a few years ago, Schulmann received her birth certificate which had been issued by the camp authorities -- a "priceless gift".

A vestige from Berger Moran's past is on display at the Mauthausen memorial in the form of a tiny dress sewn by detainees who were at the Freiberg camp at the same time as her mother, an exhibit which school students find particularly touching.

Berger Moran and Olsky had planned to be in Austria for the 75th anniversary of the camp's liberation on May 10, but for the first time since 1946 the event will not take place because of the novel coronavirus pandemic.

A virtual ceremony will be held instead, while the task of educating the next generation -- and of sounding the alarm over troubling events in the present -- continues regardless.

"We are the last ones and we better make that message very strong because after we are gone, will people still remember?" Berger Moran asks.