Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsKalis Mardiasih’s bold, moderate Islamic interpretation of 'hijrah'

Choosing a more moderate approach, I sometimes question myself, am I not Muslim enough if I don’t follow this hijrah trend?

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

B

orn and raised as a Muslim in Indonesia, I can’t help but notice the increasing popularity of the hijrah (migration) movement, especially among the young generation of Muslims in Indonesia.

The transformation of young people from cultural Muslims into more devout ones has become more visible in recent years. From fashion to food, property to relationships, this hijrah trend has begun to dominate the mainstream narrative in Islamic society. One local brand even claims to offer the first halal certified hijab in Indonesia, which has made me question my own hijab collection. Is it not halal?

Sharia residential complexes, built exclusively for Muslim families, have been in high demand, as more and more Muslims seek comfort in living in a more homogenous community.

Offering membership, seminars and guidebooks, the social movement called Indonesia Tanpa Pacaran (Indonesia Without Dating) encourages people to break up with their partners and choose to pursue marriage through taaruf (an Islamic process through which couples get to know each other).

Choosing a more moderate approach, I sometimes question myself, am I not Muslim enough if I don’t follow this hijrah trend?

In 2018, the first-ever Hijrah Fest was held at the Jakarta Convention Center, drawing more than 15,000 visitors over three days. The event was so successful it became an annual program. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, the festival continued to be held virtually as “Hijrah Fest from Home”.

If you search for the hashtag #hijrah on Instagram, more than 10.5 million posts will appear. One of the most popular figures in the hijrah movement, Hanan Attaki, the founder of SHIFT Pemuda Hijrah, has 8.3 million followers on Instagram. On YouTube, the channel Tafaqquh, owned by Ustaz Abdul Somad Batubara, has more than 1.7 million subscribers and earns more than Rp 300 million (US$20,189) a month.

Rahmat Hidayatullah, a lecturer at Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University, said the hijrah phenomenon in Indonesia had been on the rise recently because it had been repressed for so long by the New Order regime. He added that many Indonesian students learning in Saudi Arabia in the mid-1980s had brought home the local ideology and culture and shared it through their dakwah (Islamic preaching) back in Indonesia.

Najib Kailani, a lecturer at Sunan Kalijaga Islamic State University, said the term hijrah appeared in the 1990s when Islamic communities at universities started to actively conduct liqo and halaqah (Islamic mentoring session) programs for students, after the fall of Soeharto.

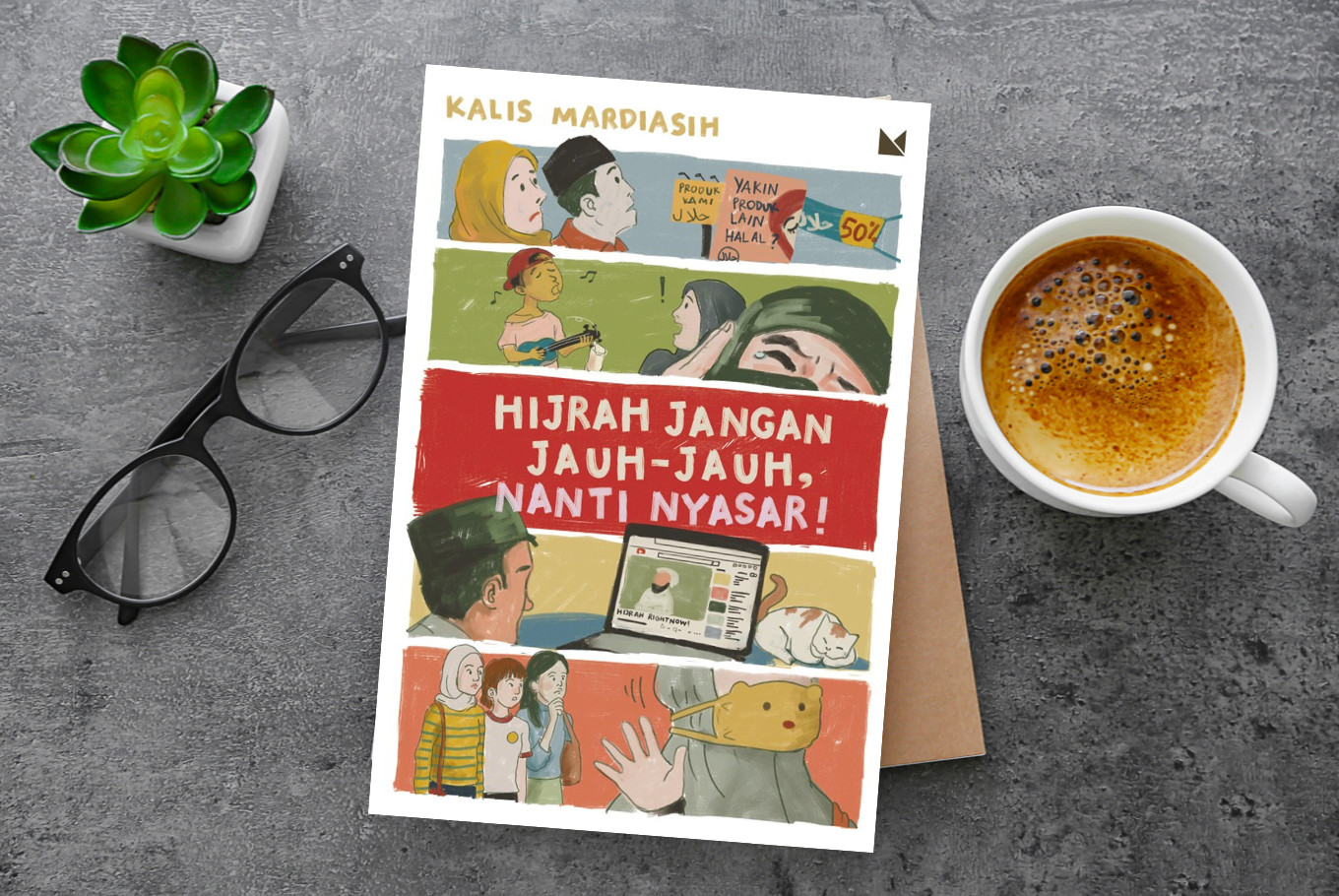

With the hijrah movement having become a hot topic of conversation among Indonesians, whether at informal social gatherings or on social or mass media platforms, a collection of essays titled Hijrah Jangan Jauh-Jauh, Nanti Nyasar! (Don’t Go ‘Hijrah’ Too Far, You’ll Get Lost!) by Kalis Mardiasih has shed light on this issue through relatable personal stories framed within sound social, political, historical and psychological analysis, combined with sound Islamic theological analysis.

Kalis Mardiasih is a writer and activist from Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest mass Muslim organization. She is also a member of the national secretariat of GUSDURian, a network for those who admire the fighting spirit of Indonesia’s fourth president, Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid, in promoting pluralism. She is also the author of Muslimah yang Diperdebatkan (Muslim Women Who Were Contested) (2019) and Sister Fillah You’ll Never be Alone (2020).

In her book, she shares a story about her colleague’s elementary school-age daughter who came to her and said, “I want to have a different mother. I want Aunty Kalis to be my mother, because you wear a hijab. My mother doesn’t wear a hijab." She criticizes how children nowadays react to this hijrah phenomenon by asking what is halal and what is haram, even asking if they can play with friends of different religions.

Discussing the shifting identity politics among Indonesian Muslims from the colonial era to contemporary times, this book offers insights into the different challenges faced by Indonesian Muslims throughout the course of history. Kalis argues that the use of religious symbols, such as the Ar-Royah flag, to trigger fear and anger among the Islamic community today is misplaced because we are currently living in an inclusive social system.

Religious symbols cannot solve the social, economic, technology and social justice issues faced by Indonesians today. In the past, Indonesian Muslim scholars used Islamic symbols, such as sarongs and turbans, to differentiate themselves from their oppressors.

But their fight against colonial injustice didn’t stop with symbols, as they build academic institutions to educate Indonesia’s younger generations, who came to be key to the nation's attainment of independence and freedom. By focusing only on religious symbols and texts, Muslims will lose the ability to think critically and fall into the hands of religious traders who will keep people in the unknown in order to control them.

By Quranic definition, hijrah means a migration from evil to goodness. In general, this movement is a positive activity that aims toward a better way of life based on Islamic values. However, many experts have raised concerns that a growing religious revival in Indonesia could lead to exclusive attitudes and a sense of religious superiority among those who have performed hijrah, believing that leading a certain way of life can make someone more Muslim than other Muslims.

Instant and drastic religious transformation through hijrah without proper and structured knowledge as a foundation can lead to religious exclusivism, social and ideological alienation, or worse, religious extremism.

The sudden urge to become more religious is not unique to the hijrah community. In Etgar Keret’s book, The Seven Good Years (2015), he tells a story about his sister who suddenly become a religious person and how his father, a Holocaust survivor, always encourages Keret to live a religious life because in a time of war, being a religious person is the best alternative to find peace.

There are many factors that drive individuals to become more religious, including war, illness, divorce, or the death of loved ones. Growing up, our social circle will expand or change. This can also lead to a behavioral transformation and changes in religious views.

Kalis’ father taught the Quran to children and housewives in their neighborhood for free. He did it humbly, selflessly and consistently. Coming home from the university where she became involved in student activism and religious study at the campus’ mosque, one day Kalis asked her father, “You have taught Quranic studies for a long time, why has your teaching not progressed?”

Being raised within the pesantren (Islamic boarding school) tradition, Kalis understands that the first step in learning Islam is to study akhlak (the practice of virtue, morality and manners). But at that time, her college education and knowledge of Islamic studies made her feel smarter and perceive herself as a better Muslim than her father, resulting in her being more righteous than kind. But after a while, she felt regret, terribly embarrassed by her actions, and rushed to apologize to his father.

This essay collection really resonates with me as an Indonesian Muslim who believes that religion should be easy, simple, beautiful and inclusive. Unfortunately, since the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, I have personally felt the deep polarization and religious tension, creating a misconception that the more stringent we are in following our religion, the more pious we become, and the more Muslim we are than other Muslims.

This book helped me overcome my anxieties regarding the negative aspects of the hijrah movement, by providing further references regarding the issue, including social, political and historical context, anecdotes from the author’s daily life, and references to some of the most prominent Islamic thinkers both from Indonesia and the wider Islamic world.

For me, reading this book is like having a conversation with Kalis Mardiasih, as a fellow Indonesian Muslim who has the same concerns about the shift in religious beliefs and behaviors within the Islamic community in Indonesia, but with richer insights, as she knows more about the subject than I do.

It gives me a reassurance that it is okay to choose a moderate approach to being a Muslim in Indonesia and I am not less of a Muslim, even if I don’t follow this hijrah trend. (kes)

***

Aqmarina Andira works at an IT and technology company as a corporate secretary and government relations manager. She loves reading, hiking and traveling in her leisure time and is a cofounder of Rumah Cerita, a creative writing community for children and youth, and also cofounded the Baca Rasa Dengar book club in February 2015.