Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBribes, lies and black sticky rice: Indonesians outsmart 'mudik' ban

The government has banned people from returning to their hometowns for Idul Fitri since the pandemic begun last year. The Jakarta Post spoke to those who have braved the ban, breaking the law to fulfill the annual rite.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

ast year, university student Hakim (not his real name), armed only with courage and reckless abandon, traveled 338 kilometers from Yogyakarta to Gresik, East Java, his hometown, to reunite with his mother.

“My mother sulked when I said I couldn't go home because the government had forbidden it. She didn't want to answer my call. Rather than having her feel abandoned, I decided to just go home. She's the only parent I have left. I would do anything for her," the 25-year old recalled.

By the time Hakim made that decision, it was one day before Ramadan, a risky time to get stopped by officials tasked with catching people trying to go back home. Still, Hakim had a friend give him a ride from Jogja to a bus station in Kudus regency in Central Java four hours away to get on a bus that would take him to Gresik.

By the time Hakim arrived at the bus station, he discovered that bus operations had been fully stopped due to the ban. He had put his hopes on Kudus because it was a small town and thought officials would be more lax in enforcing the ban.

He attempted to hitchhike on trucks (last year trucks carrying goods were still allowed to move between cities) but none were heading in his intended direction. After an hour, a truck carrying ketan hitam (black sticky rice) stopped. The driver told Hakim he was heading to Gresik.

It was a perfect hideout. Had he used a bus, the risk of getting stopped at a random check point was high, but hiding on the back of a truck carrying food materials made getting caught far less likely.

"I rode on the back load. Yeah, with barrels of ketan hitam. I didn’t much mind the smell. Fish or anything else, I'd still have jumped on. Anything, as long as I could go home. I had Rp 500, 000 [US$34.91] in my pocket, in case the driver asked. But he didn't. The driver was decent. He felt sorry for me and didn't charge a fare.”

During the trip, the driver did not stop interrogating Hakim, he was worried that Hakim might be a bajing loncat (literally jumping squirrel, a truck hijacker). When they arrived in Tuban, their journey had to stop because the city's main bridge was being repaired. They chatted, and Hakim was candid about the reason he was going home to meet his mother. After that conversation, he was asked to sit in the front with the driver and was escorted to the front of his house. They had already passed all the possible checkpoints where he could be caught.

"My mother was really touched knowing that I did my best to get home,” Hakim said.

Going the rat routes

In contrast to Hakim, Parti (not her real name), who works in Jakarta as a domestic servant went through jalan tikus (literally rat routes, narrow alleys) and shortcuts to get from Jakarta to Cilacap, Central Java, and avoided places where police were likely to conduct roadside checks. Together with friends, they gathered up Rp 600,000 and rented a minibus to drive along steep rocky roads.

The 12-hour journey was a longer trip than usual, since they had to navigate lesser-traversed but far-longer routes. "Thank God, we didn't get stopped and managed to reach our homes.”

Hengki (not his real name), a 25-year old office worker, went back home a few short days before the ban started (a tactic used by many) but was forced to return to Jakarta early when his office cut its employees’ holidays short. Because the ban was still in place, Hengki had to rent a minibus for a higher price than usual.

“The fare almost doubled. Usually, we had to pay Rp 200,000 - Rp 250,000 but this time it was Rp 550,000. But come hell or high water, we just went for it,” Hengki said.

The increase in cost was not simply because the minibus owner was trying to make a buck but because the driver would have to pay off officers who manned the checkpoints to let them go - as well as gang members who blocked routes. The driver also used a WhatsApp group chat filled with drivers who kept each other informed about roadblocks and security checkpoints. Hengki also alleged that the drivers had an understanding with some security checkpoint officers.

“It was a well-oiled operation. We were stopped by the police when we arrived at Cikampek [in West Java]. I was thinking, 'Wow, we'll be told to turn around'. But apparently not, and the police actually told us access routes that led to the villages, which brought us to the Cikarang industrial area,.” Hengki said, laughing.

This year, Hengki plans to travel home in a similar manner, with a driver who has connections (his office’s leave is not in accordance with government's regulations).

"The travel cost this year will go up again. But what can you do?" Hengki said, sighing.

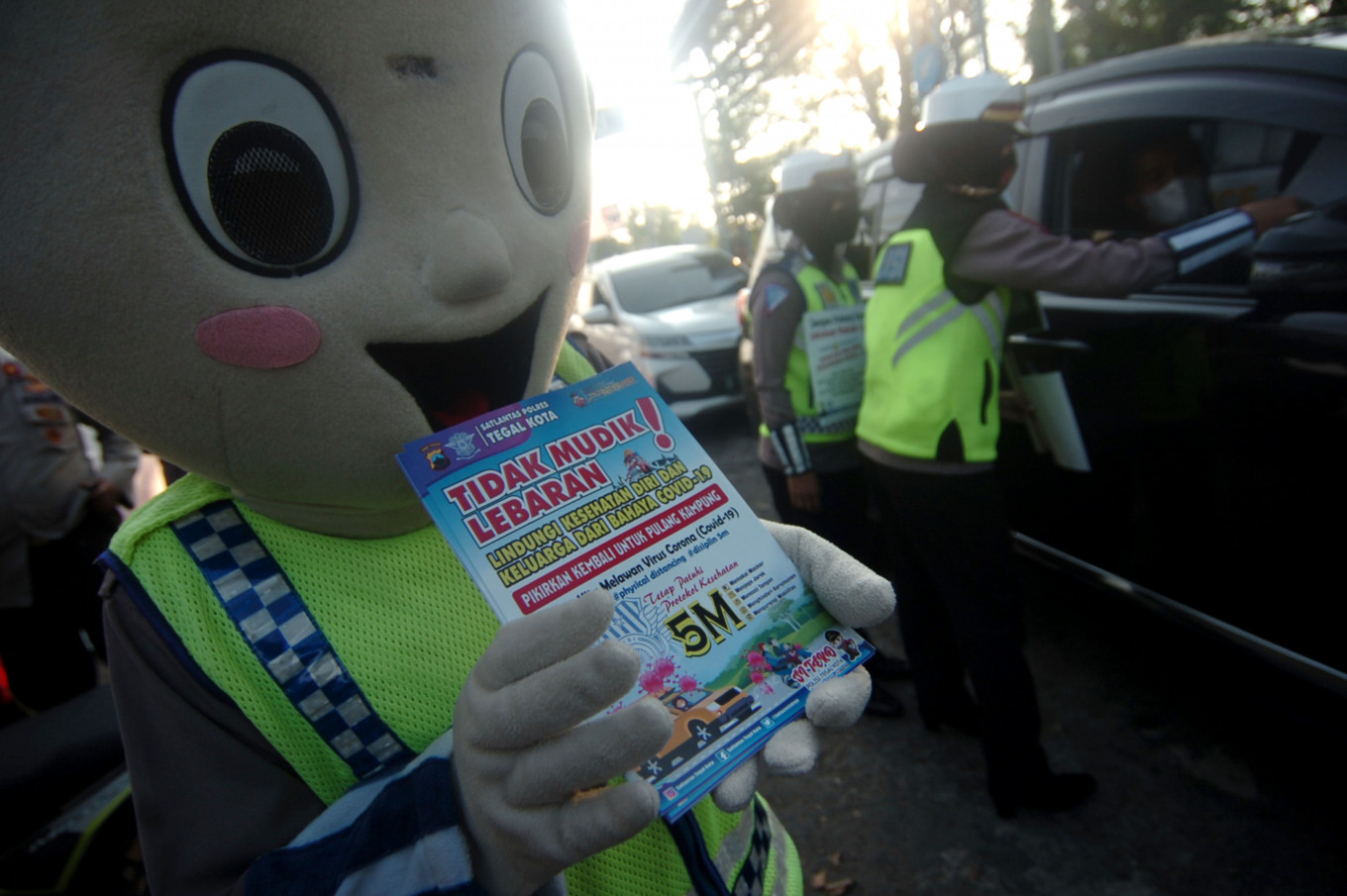

An official of the West Java Transportation Agency holds motorists in Kalimalang, Bekasi, West Java on Monday, April 27, 2020. Authorities open checkpoints in Jakarta borders to hold homecoming travelers from leaving the city amid the government's mudik (exodus) ban to curb the COVID-19's spread. (Antara/Fakhri Hermansyah)Relax, stay calm and lie

Baskoro (not his real name) claims he has had no problem going back and forth the 850 km between his native Malang in East Java and Jakarta, where he works in construction. The 24-year old goes home primarily so that his elderly mother can meet her grandchildren. Along with his four children and his wife, he regularly travels back via the toll road, where checkpoints are plentiful. He has experienced many stops by officers but always manages to get through. He says the key to getting through is simple: stay calm, act casual, and lie through your teeth.

Baskoro has passed many checkpoints but looking the officer straight in the eye and uttering the words: “I am just looking for food to celebrate Idul Fitri with my family.”

Baskoro cannot stop laughing as he tells his story.

"I was stopped many times in many cities, and I simply say that I am out looking for food. What a journey to find a meal! From Malang to Jakarta just to get a plateful of food.”