Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFasting and the ethics of reciprocity to ‘the other’

The time has come for Muslim preachers to prepare what they will deliver in the daily sermons during the coming Islamic fasting month of Ramadhan

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

The time has come for Muslim preachers to prepare what they will deliver in the daily sermons during the coming Islamic fasting month of Ramadhan.

Ramadhan is probably the only time in which Islamic sermons will talk more about ethics, morality, patience and anything related to controlling emotions — as these are among the key meanings of fasting — rather than issues pertaining to Islamic identity and politics. The Arabic word for fasting, siyam or sawm, literally means “to refrain/abstain from something”.

The ritual obligation of fasting is to abstain from the physical needs and desires: eating, drinking and having sex during daylight hours.

Yet to perfect one’s fasting and upgrade his/her spiritual level, s/he should refrain from negative emotions (anger, envy, arrogance, hatred, etc.) and materialistic ambitions to achieve, as the Koran explicitly says, la’allakum tattaqun (consciousness of God).

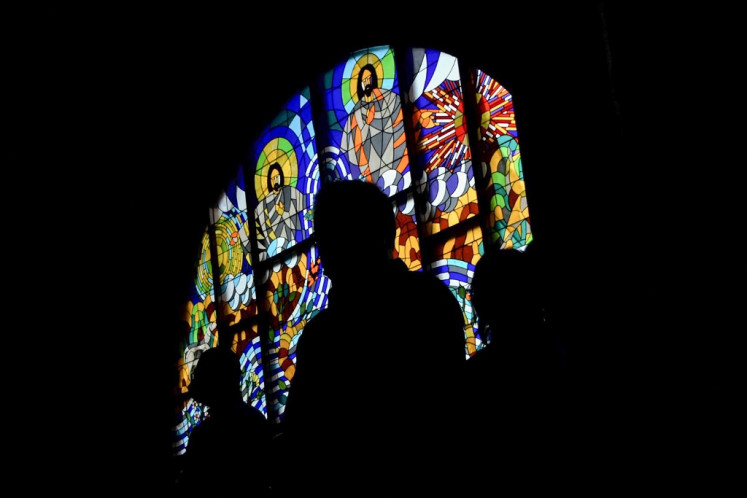

This teaching of refraining from materialism to enhance spirituality is shared by other religious traditions through various methods including fasting.

All these are good, of course, and maybe more needed for Muslims nowadays after the last few years of rising intolerance and radicalism.

After 11 months Muslims have been exposed to sermons filled with theological debates spreading hatred and sectarianism, Ramadhan should be an interlude for self-criticism and, more importantly, reevaluating the way Muslims have dealt with the other.

Among the sermons that preachers often deliver during Ramadhan is that fasting is for Muslims to experience the life of the poor and needy.

Even though this is not the rationale of Islamic fasting ritualistically, it is a hikmah (wisdom) embedded in fasting’s spiritually: It is an act of solidarity for Muslims to put themselves in the shoes of those less fortunate than them.

As a result of this developed empathy, fasting is a manifest of the ethics of reciprocity or the golden rule — don’t do unto others what you don’t what others do unto you; or, in the words of the Prophet Muhammad, “one is not a [real] believer until s/he wishes for his/her brother what s/he wishes for him/herself.”

What does this have to do with intolerance and sectarianism? It means that in addition to the poor and needy, the group that Muslims should develop an empathy with are the marginalized, dispossed, persecuted people, not only of other religions but also fellow Muslims from different sects, such as Shiites and Ahmadis. Like the poor they are politically impoverished for their civil rights have been curtailed.

Therefore fasting is also to be in the shoes of those persecuted people. This is important because at the heart of Muslims’ intolerance is the lack of empathy, of seeing themselves from the others’ perspective.

This is partly due to the mindset of supremacy that has developed more prominently among Indonesia’s Muslims, leading to the curtailing of rights of minorities.

This (Sunni) Muslim sense of supremacy has resulted in judging others as deviants and worse, blasphemous defamers who are worthy of persecution and even eradication. Civil rights and equal citizenship are sacrificed on the grounds of public order that privileges the majority.

Such a mindset can be changed if we could at least try to imagine what if we were in the minorities’ shoes living, say, in the West, especially in countries where both anti-Islam and excessive nationalism are rising following the wave of immigrants from the Middle East.

Many of the minorities are considered alien, deviant, a danger to public order, etc., and as such discriminated against, expelled or worse killed.

Being deviant is relative. If being deviant means having different beliefs, Muslims are deviant in the eyes of Christians, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, etc. and vice versa.

Worse, each sect within Islam can see each other as deviant. Imagine what the world would be if being deviant means worthy of persecution because being deviant is defined as having different beliefs.

Fasting, therefore, can and should help cultivate empathy, which in turn paves the way for more tolerance toward people of other beliefs.

This is certainly no less important than to be empathetic toward the poor economically — which is sometimes also ignored by Muslims whose consumerism ironically increases despite the fasting month.

Besides, fasting should also remind Muslims that Islam is not only a religion of creed and law. The very meaning of fasting should remind us that Islam has a large dimension of spirituality.

There have been efforts from some Muslim groups to reform Islam, to bring it back onto its right track, by stressing spirituality and love, instead of law and punishment, at the center of Mulim discourse.

This effort can be improved by, among others, enhancing discussion on the importance of the ethics of reciprocity in Muslim communities. Ramadhan is a good moment for preachers to take up this theme.

______________________________________

The writer is a graduate fellowship recipient at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. He is a masters student in religious studies at Gadjah Mada University.