Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsCOVID-19: Does Indonesia need a lockdown? It depends on how you define it

What exactly does a lockdown entail? How does it differ from community quarantine?

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

t seems that at the height of any crisis, a buzzword tends to pop up and dominate public discourse due to the sheer frequency of its usage by state officials and ordinary people alike.

During the current public health crisis caused by outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which the World Health Organization has officially declared a pandemic, that buzzword seems to be “lockdown” – a term that carries apocalyptic connotations and imagery, thanks in no small part to popular culture.

But what exactly does an actual lockdown entail? How does it differ from community quarantine?

Most importantly, does Indonesia – with its ever-increasing number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, 227 at the time of writing – actually need to impose a lockdown?

To answer the above questions, one must first understand the basic definitions of the terms.

Lockdown? What lockdown?

According to Bayu Krisnamurthi, who headed the National Committee for Avian Flu Control and Pandemic Preparedness in Indonesia, the terms lockdown and community quarantine are synonymous in that both are used interchangeably to refer to a type of quarantine in which all citizens in a certain region are prohibited from going in and out of the territory without official permission from authorities.

In terms of scale, quarantine procedures vary from self-isolation – which entails confining confirmed or potential patients to observation in their homes – to lockdown, also known as community quarantine.

In practice, however, quarantine protocols are more nuanced than they may seem on paper. For example, some countries have imposed “total lockdowns”, while others have merely decided to implement “partial lockdowns” – that is, controlling the movement of their population by imposing a “general community quarantine” or, in a slightly bleaker situation, an “enhanced community quarantine”.

Read also: Social distancing and super-spreaders: Coronavirus lingo goes viral

The first country to impose a total lockdown during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak was China. The country implemented the emergency protocol in the outbreak’s epicenter of Wuhan, Hubei province. The city’s population of 11 million was kept from leaving Wuhan to contain the spread of the disease.

However, as the number of confirmed cases and fatalities quickly grew in other regions across the province, the Chinese government scrambled to put 15 other cities including Huanggang and Ezhou on lockdown, affecting nearly 60 million people.

Chinese-style lockdown

Throughout the lockdown, the Chinese government issued an order to shut down all non-essential companies and schools, and it banned certain modes of transportation.

China’s efforts have paid off in recent weeks as the country reported fewer than 200 new cases of infection per day, a drastic fall from the about 3,000 new cases recorded daily last month, as reported by the South China Morning Post.

Despite its apparent efficacy, the lockdown has taken a toll on the country’s social cohesion, with public protests and disturbances becoming increasingly common across affected cities as residents complain about the surge in prices for staple foods, among other things.

As of the time of writing, China has recorded a total of 80,881 cases and 3,226 fatalities.

In Europe, a number of countries including Italy – the hardest-hit country in Europe and the second hardest-hit nation globally after China – have followed suit and have imposed what has been dubbed a “Chinese-style lockdown” in several major cities since the WHO declared the region a new epicenter of COVID-19 on Friday.

The entire country of Italy has been put under total lockdown, with Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte extending restrictions already in place in “red zones” in the northern provinces to the rest of the nation, CNN reported.

Italy’s healthcare system is overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients that have to be given immediate treatment. The country has 35,172 confirmed cases and 2,937 fatalities at the time of writing.

Similarly, France has taken a hard-edged approach to the pandemic by imposing a total lockdown throughout the country, akin to the ones implemented in China and Italy. French President Emmanuel Macron said during a press conference that strict confinement was the only effective weapon against the virus. It has infected more than 6,600 and killed 148 in France, as reported by AFP.

The French lockdown entailed the deployment 100,000 police officers to patrol the streets, as well as a $150 fine for any violation of the emergency protocol.

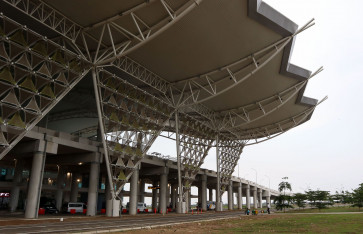

Commuters take the Woodlands Causeway to Singapore from Johor a day before Malaysia imposes a lockdown on travel due to the coronavirus outbreak in Singapore March 17, 2020. (REUTERS/Edgar Su)Partial lockdown

In contrast, South Asian countries have implemented comparatively lenient restrictions, probably due to the fact that the number of confirmed cases and deaths in the region is nowhere close to the number recorded in other, more affected regions.

Instead of a fully-fledged lockdown, Malaysian Prime Minister Muhiyiddin Yasin announced earlier this week a “movement control order” – also known as a partial lockdown – that restricts mass gatherings from March 18 to 31. In addition, the order bans all overseas travel to and from Malaysia and closes all schools, government offices and private businesses except “those involved in providing essential services”.

However, despite the seemingly stringent rules, the Malaysian government is still allowing its citizens to leave their houses to purchase groceries and other essentials. Certain outdoor activities such as jogging and exercise are still allowed, provided that Malaysians avoid close contact with each other.

Malaysia has confirmed more than 500 COVID-19 cases at the time of writing.

Read also: How a 16,000-strong religious gathering led Malaysia to lockdown

In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte has put the Manila metropolitan area under general community quarantine and the entire island of Luzon under enhanced community quarantine from Mar. 17 to Apr. 13.

Whereas the general community quarantine is essentially identical to Malaysia’s movement control order, the enhanced version is closer to a total lockdown – but still not as stringent.

During an enhanced community quarantine, the government strictly regulates food provisions and healthcare. It also increases the presence of uniformed personnel on the streets to enforce quarantine procedures, according Philippine Interagency Task Force spokesperson Karlo Nograles.

Private establishments providing basic necessities such as convenience stores, markets, hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and delivery services – among others – are allowed to remain in operation during the enhanced community quarantine.

What about Indonesia? A partial lockdown is an option

The above cases present Indonesia with an abundance of options, each with its own strengths and limitations, as the government considers how to best stem the spread of COVID-19 in the country.

Indonesia has yet to issue any stringent regulation beyond its campaign to promote social distancing. The government is reluctant to conduct mass testing to isolate confirmed cases, one of the only alternatives to implementing a lockdown in the face of the worst pandemic in recent history.

The government is expected to act fast, with scientists calling for a community quarantine ahead of Idul Fitri, when the country’s predominantly Muslim population travels to hometowns and villages across the archipelago, thereby increasing the risk of a nationwide outbreak.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has called on the public to work, study and worship from home to prevent a nationwide outbreak, but he stressed that the government was “not leaning toward issuing a lockdown policy” at the time.

"I have to emphasize that issuing a lockdown policy, either at the national or regional level, is under the authority of central government. Such a policy cannot be issued by regional administrations," Jokowi told a press conference on Monday.

However, if push comes to shove, as it likely will in the coming weeks with the approaching Idul Fitri holiday, scientists seem to have agreed that imposing a partial lockdown is Indonesia’s best bet.

Members of the Indonesian Young Scientist Forum (IYSF) have called on the government to impose a lockdown on areas considered outbreak hotspots.

“Measures to limit crowds and the movement of individuals in vulnerable areas should be maximized if the number of [confirmed] cases per day doubles,” the forum said in a letter addressed to Presidential Chief of Staff Moeldoko.

IYSF member Berry Juliandi from Bogor Agricultural University said a partial lockdown was the most fitting option since it would still give the public a degree of freedom. “It would be better if [the government imposed] a partial lockdown. It limits individual movement but still allows access to essentials,” Berry said.

Indonesian passengers wearing face masks ride a Trans Jakarta bus on March 18, 2020. (AFP/Adek Berry)Island lockdown?

Airlangga University scholar Nidom, who also helms the Coronavirus Research and Vaccine Formulation Team, said that if the government decided to impose a lockdown due to future escalation, it should implement an island-based lockdown, instead of the usual city-based lockdown, considering the country’s vast archipelagic expanse.

“A lockdown is feasible but only if it’s not imposed in individual cities [...]. It would be better if [the government] imposed an island-based lockdown instead. Indonesia is an archipelagic state, the sea could serve as the best isolator,” he said.

In Java, for example, such a measure could be carried out successfully assuming that all regional heads on the island joined forces and issued joint policies for the island’s entire population, instead of contradicting each other if left to their own devices, he said.

Furthermore, such a massive undertaking would require greater involvement from members of the public as well as a concerted effort on the neighborhood level, such as turning houses of worship into shelters for COVID-19 patients, Nidom said. However, in such a scenario, schools and offices would remain operational as usual, he added.

Bayu said that although the lockdown remained a viable option, the mitigation of the pandemic could ultimately be accomplished through a strict social-distancing protocol.

“Social distancing serves as an alternative to quarantine,” Bayu said. “The spread of the coronavirus can mainly be prevented by not touching infected objects and other people, as well as not touching our own faces.”

Editor's note:

This article has been updated to correct the number of COVID-19 cases in Italy.