Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsQuestioning history through Indonesian cinema

Most movies loaded with history are intended to reenact a historical event or to glorify a historical figure. But is there still room for experimentation?

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

istorical movies don’t even need to be all that factual. A typical example is the many movies with plots that reference Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party, his personal life, the Holocaust, and the world war he started during his dictatorship.

Quentin Tarantino’s critically acclaimed Inglourious Basterds and Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit, as well as satirical comedies by German filmmakers like David Wnendt’s Look Who’s Back and Sönke Wortmann’s How About Adolf?, are just some of the hypothetical (alternative history) biopics we can watch today.

In comparison, the catalog of Indonesian historical movies is relatively pale, with Azhar Kinoi Lubis’ Surat Cinta Untuk Kartini (The Postman and Kartini, 2016) the most recent example. The film tweaks the life story of the national heroine to involve a romantic affair with the mailman.

“As a movie buff myself, I’m bored of how Indonesian films inspired by historical events or people are presented,” said filmmaker Yosep Anggi Noen.

“They are always linear and carry the nationalist utopia [narrative] that leaves no room for viewers to start a conversation about [real] history,” he added.

He was speaking during “History on the Screen” as part of Bingkis (Bincang Kamis), a Goethe-Institut Indonesien public discussion series that aired on YouTube every other Thursday from June 18 to Dec. 17. The video recordings are still available for viewing.

Expounding, Anggi said that filmmakers had a “poetic license” to take what they find in archives and history books and interpret these in a compelling and digestible format.

For filmmakers to succeed in creating their own “cinematic truth”, he continued, they had to pass public scrutiny on the accuracy of the details they depict in their films, as well as their chosen film genre.

Critique and criticism: Actor Gunawan Maryanto appears in a still from 'Istirahatlah Kata-kata' (Solo, Solitude), Yosep Anggi Noen’s 2016 feature film about poet and activst Widji Thukul, who disappeared at the end of the New Order regime. (Courtesy of KawanKawan Media/-)Anggi faced such scrutiny over his 2016 fictionalized biopic on the poet and political activist Wiji Thukul, Istirahatlah Kata-kata, which roughly translates to “rest in words”, but was released internationally as Solo, Solitude. One criticism, for example, pointed out a van that had not been produced in 1996-97, when the events in the film took place.

“It’s a fiction, not a documentary,” said Anggi, adding that some events in that particular scene were made up to emphasize the social and political undercurrents of the time as Wiji fled persecution under the New Order regime before he was declared missing in 1998. These included trivia about the poet-activist and Anggi’s personal interests.

Film researcher and lecturer Umi Lestari said Indonesian cinema had many historical movies that explored a variety of various plots and genres.

She said that filmmakers began portraying Indonesian youth in romantic dramas in the early 1940s, before Indonesian independence, and when Chinese-run production houses dominated the industry.

“But the characters were presented as easy-going young people who had no concern whatsoever about the country’s affairs at that time,” said Umi.

National identity started becoming the mainstay theme of movies released in the 1950s, as seen in the works of Usmar Ismail and the state-backed production house, Perfini.

Although these movies were based on their makers’ personal experiences and independent researches, the majority were formulaic visualizations of certain historical events.

Those that break the mold include Si Pintjang (The Cripple, 1951) by director Kotot Sukardi, who was a member of the art and cultural organization Lekra that was affiliated with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) that was banned in 1965.

The film follows Giman, who was born disabled, who joins a group of street children to survive the pre-independence Japanese occupation and post-independence Dutch attempt to reclaim Indonesia.

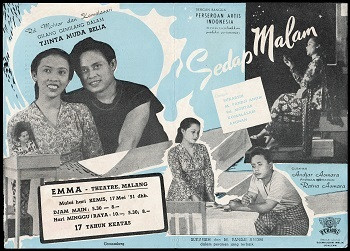

Untold story: The promotional poster for 'Sedap Malam' (Tuberose, 1951) by Indonesia’s first female director, Ratna Asmara, appears to give no clues as to its sensitive topic it explores through its protagonist, Patma, who becomes a comfort woman during the Japanese occupation of pre-independence Indonesia. (Courtesy of filmindonesia.or.id/-)Another is Sedap Malam (Tuberose, also Sweetness of the Night, 1951) by Indonesia’s first female director, Ratna Asmara. In it, protagonist Patmah becomes a prostitute when she is abandoned by her husband for a younger woman. The film is credited for starting a discourse on sexual slavery during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia.

In her research, Umi found that Indonesian historical movies of the 1970s and 1980s generally represented the state’s version of history, but these were balanced out by B-grade comedy movies like Nawi Ismail’s Benyamin Tukang Ngibul (Benyamin the Liar, 1975).

“The film is a kind of commentary on the government program to deploy the military to villages. There is a scene when Benyamin fishes a military-issue boot from a pond and he [becomes involved] in a series of unfortunate events since,” she explained.

With the advent of the reform movement in the mid-1990s, Umi said the genre grew more varied, dominated by biopics.

“Many investors wanted to have their ancestors included in the nation’s historical [consciousness],” she said, adding that the biographical films shared some other similarities.

“The plot is always linear, the main character is always depicted as heroic, and they are made to precision. Our filmmakers are yet to explore communicating [through imagery], as they rely on the lines in the dialog to convey a story,” she said.

Anggraeni Widhiasih, who curated the 2018 Jakarta International Documentary and Experimental Film Festival (Arkipel), said that Anggi’s most recent release, Hiruk Pikuk si al-Kisah (The Science of Fictions, 2019), questioned the national memory while juggling historiography and propaganda using the audiovisual medium.

The offbeat dramedy, which received a Special Mention Award and was nominated for Best Film at the 2019 Locarno International Film Festival, was laden with Anggi’s own take on historical events, personal reminiscence and audiovisual reconstructions that demonstrated the power of moving images in today’s disinformation era.

“On many occasions, people refer to films and not newsreels to explain an event or phenomenon, but in the current [era], film is no longer the sole audiovisual reference,” said Anggraeni.

“The mainstream narrative of history now competes with the history that people write today, sharing their side of the story on user-generated content platforms,” she explained.

Meanwhile, Anggi noted that media literacy was crucial for filmmakers to experiment with historical films and documentaries.

The director’s 2014 short film Genre Sub Genre, which won that year’s Arkipel Jury Award, was an experimental black-and-white video that documented the landscape in Nusa Tenggara. It caused a stir with scenes that showed a train passing through a region that doesn’t have a railway and a giant paper boat sailing on a lake.

“Our audience tends to clarify the truth before watching audiovisual products instead of just enjoying them. It’s a bit unfair because people can enjoy a painting or a dance performance without questioning the art, although these also try to capture the zeitgeist of the era,” said Anggi.

“I think filmmakers have a responsibility to disrupt an audience’s moviegoing experience and to exhibit their work at commercial spaces instead of underground screenings to stir up conversation about media literacy,” he said. (ste)