'Hostile' public spaces: Are they really for the public?

Call it the pursuit of "modernization" or the modern esthetic, but public spaces filled with facilities, structures and other ar elements that make them unaccommodating to the end-user (that would be us, the public) aren't fulfilling their basic function, never mind inclusiveness.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he facilities and structures of a public space should be open and accessible to the general public as a whole, without any features that could be discriminatory against any particular group.

Simply put, badly designed public spaces are inhospitable to the ordinary folks they’re meant for.

“In MRT stations, all the benches are the same slatted benches with noticeable gaps. From what I’ve seen, they’re really not convenient for older people, [and] there are no special seats designed for them,” observed Shereen, a 26-year-old content marketing manager who commutes to work on the Jakarta MRT.

“As for the Commuter Line, before renovations, the benches were actually decent enough. After they were changed into the frame-like ones that you can’t actually sit on, it’s more difficult to rest between your commute,” she said, referring to the so-called leaning benches featuring horizontal bars at Commuter Line train stations.

These types of urban facilities are called “hostile architecture” or “defensive urban design”, and are a way of controlling societal behavior through built environments. Common examples include the leaning benches above to deter people from sitting too long, or park benches with divider arms to prevent people from laying across them.

Such features in public spaces pose a paradox: Why are public spaces being designed so they are unwelcoming to the public?

“Strangely, in larger transit areas like Tanah Abang or Manggarai, all the benches are [leaning benches]. I get that it’s just supposed to be a quick stop, but the waiting time [between] trains can be up to 30 minutes, so there’s a lot of [passenger] congestion. People resort to sitting on nearby stairs and against the [station] pillars,” Shereen said of the facilities at Commuter Line stations.

KAI Commuter, which operates the Commuter Line train service, has not responded to a request for their comments.

The sentiment is not universally negative, however.

Dino, a 24-year-old commuter, said that the public facilities at Commuter Line stations were adequate. “Since [the stations] are only intended for a quick transit, I feel that the facilities are appropriate for the purpose. In normal circumstances, the waiting time for trains is just 15 minutes,” she said.

She also felt that she greatly benefitted from the fast-track facility for priority passengers, which offered direct boarding services with the assistance of station staff. Regular passengers, on the other hand, must walk through an underpass to reach a platform to avoid creating a bottleneck.

Unintentionally hostile

Design researcher and lecturer Prananda Luffiansyah Malasan at the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) said that most public facilities and built environments in Indonesia were not intended to be hostile, but said that they were harmful in their own way. In 2019, Prananda wrote an article criticizing Ridwan Kamil’s public projects while he was the Bandung mayor, specifically the Teras Cihampelas shopping mall and the Alun-Alun Bandung public square.

While some developments might please most people, they can marginalize certain groups.

For example, many public spaces used to have street vendors before they were renovated, but Prananda criticized the forcible relocation of street vendors during the redesigning project as “killing them slowly”.

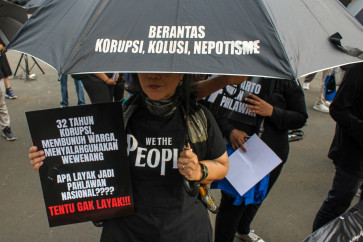

At Teras Cihampelas, the vendors were moved to the pedestrian skywalk, while they were moved into the basement of Alun-Alun Bandung. Doing so created the perception that street vendors, as part of the informal economy, were excluded from the desirable public design and the accepted vision of “modernization”. Prananda questioned the motivation behind these projects, whether they were really for the public or for instilling an image of modern development.

Prananda said that design was very human-centric as a profession, but beyond that, designers should also focus on the larger environmental context. He was concerned about the use of synthetic grass at Alun-Alun Bandung, as using the synthetic material separated people from nature. The same environmental concerns also applied to pavements and roads, most of which didn’t take into account the flow of rainwater and sewage.

“Even without getting into that subject yet, we haven’t even fulfilled the basic needs of the people. [Disability access] is still a major issue with our public spaces,” said the 33-year-old.

Seeing the tactile paving that led nowhere, it seems that these facilities have been installed more to fulfill a requirement rather than to actually help people with disabilities navigate public spaces.

Prananda, who studied for a time in Japan, said that the most distinctive difference between the public facilities there and here was that in Japan, public construction projects involved the public at every stage.

Public participation didn’t end there, he added, as the Japanese public was expected to give their feedback on how the facilities functioned afterward.

“Suppose you want to send a critique or feedback on a public space, do you know where to send it?” he asked, referring to Indonesia’s public feedback mechanism. “The public should have a say in the spaces and facilities that are intended for their use.”

Unfortunately, this level of public accountability and transparency is sorely lacking in Indonesia.

Good intentions, flawed execution

ITB lecturer Achmad Tardiyana, who also has an architecture and urban design practice, hostile architecture was almost unavoidable as long as a power imbalance existed between societal groups. Groups with power would always look to exercising control over those with less power.

One way to do this was to install a structural deterrence to restrict certain groups from specific areas, which was commonly found in Indonesia’s commercial spaces.

As for informal enterprises, Achmad said the issue had no simple solutions, underlining that catering to everyone was impossible. Issues like this were unique to nations like ours, where access to livelihoods was largely unequal. They were thus structural issues that could not be solved by urban design alone.

“I like the ‘messy vitality’ that can be found in [dynamic] areas with lots of street vendors, where people from different backgrounds can interact with each other. A city needs to have balance between these areas with ones that are more neat and ‘sterile’,” said the 60-year-old lecturer and architect.

However, Achmad noted that in recent years, the government had taken greater care and concern to develop better public spaces and facilities in different cities by involving architects and urban designers. Limited funds and the involvement of multiple parties in construction projects were among the factors that contributed to their complexity. The execution was still far from perfect, but he said it was a good start.

Busy areas in Jakarta like Thamrin and Sudirman, Achmad said, were far more pedestrian friendly now.

“I hope that this is a development that will continue in the years to come,” he added.

For the ordinary public, however, the issue seems to be simply a lapse in the logic of architecture.

“What’s weird to me is that, despite the limited accessibility, restaurants and convenience stores seem to be more the focus at MRT stations. There’s even a ‘dollar store’ in one. What could you possibly need so desperately during a commute of a few kilometers?” Shereen said.

“Humanity can take a backseat. Making profits is number one.”