Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsJokowi’s hawkish approach toward anti-Pancasila movement

In the eyes of ordinary people, Islam that is based on the Quran and hadiths is more compelling than the secular ideology of Pancasila.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

J

une is often considered the “Pancasila month” because it is said the state ideology was born on June 1, 1945. Two events this month have revived an old debate over Islam and Pancasila: the controversional questions Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) employees were asked during the civic knowledge exam and the President’s speech on Pancasila Day.

The civic exam aimed to assess the ideological orientation of KPK employees, but the controversy lay in several questions that many deemed to be provocative and unnecessary, including whether the examinees would choose Pancasila or Islam.

Meanwhile, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo warned in his speech that the internet, especially social media, facilitated the spread of “radical transnational ideology” to Indonesia and that this constituted a threat to Pancasila. The President did not go into detail about what he meant by“transnational ideology”, but few could doubt that he was referring to conservative, radical Islam.

How has the Jokowi government addressed this challenge? Has his approach been effective?

When he began his first term in 2014, Jokowi was met with the same challenge that previous governments had faced in the post-New Order era: the dwindling legitimacy of Pancasila after the autocratic Soeharto regime weaponized it to suppress opposition. The rise of Islamism worsened the legitimacy of Pancasila.

In the eyes of ordinary people, Islam that is based on the Quran and hadiths is more compelling than the secular ideology of Pancasila. A survey by the Indonesian Survey Circle (LSI) found that the proportion of Muslim respondents who supported Pancasila decreased steadily from 85.2 percent in 2005 to 75.3 percent in 2018. In contrast, Muslim respondents who preferred sharia as the state ideology rose 9 percent in the same period.

Due to electoral reasons, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who was Indonesia’s president from 2004 to 2014, often seemed aloof in responding to the rise of Islamists who promoted sharia and other Islamic policies. The centrist president even accommodated them at times. This stance provided fertile ground for the transnational, populist brand of Islam to flourish during his regime. As a result, these strains of Islam had much leeway in promoting their causes, including the promotion of their version of Islam as alternative state ideology to replace Pancasila.

Shortly after assuming power in 2014, Jokowi showed an increasingly hawkish stance toward the Islamists in a marked departure from his predecessor. The secular-leaning President inspired the imposition of repressive policies on Islamists, such as a ban on Islamist media that were alleged of not only disseminating anti-Jokowi discourse, but also promoting anti-Pancasila as well as radical Islam.

Jokowi’s hawkish stance only sharpened after transnational, populist Islamist groups mounted a challenge by mobilizing the masses, which led to the blasphemy trial of his close associate and then-Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama.

Islamist groups like the Islam Defenders Front (FPI) and Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) were the driving force behind the series of street protests against the Chinese-Indonesian and Christian governor.

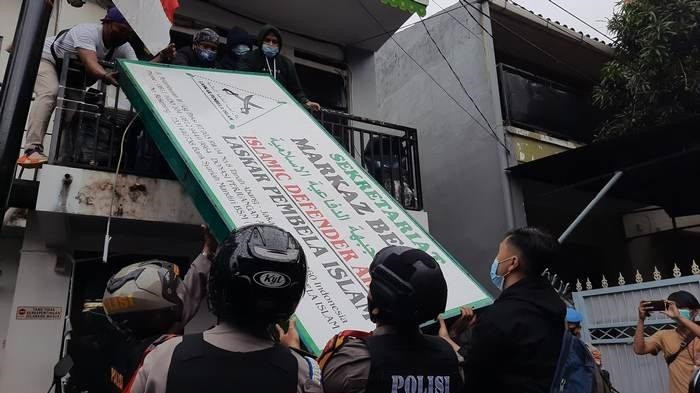

Surprised by their capacity to unite the various strains of Islam, the Jokowi government took harsher measures against the Islamists. The ban against the HTI in July 2017 and the dissolution of the FPI in 2020, as well as the prosecution of FPI leader Rizieq Shihab for violating the COVID-19 health protocols, are clear evidence of the government’s hardline approach to Islamic radicalism.

Law enforcement agencies were also relentless in pursuing legal measures against FPI leaders. At least six FPI figures have been arrested, but the most prominent among them is Munarman, the defunct group’s former secretary-general who has been charged with involvement in an act of terror.

It is safe to conclude that the state’s stringent efforts have succeeded in quelling the Islamists.

The prospect for Islamists to bounce back from their current predicament looks dim, as a survey by the Saiful Mujani Research Center (SMRC) shows that the government has won popular support for its tough stance.

Worse, the Islamists have lost an outlet that could help them amplify their aspirations: the Islamist media. A 2015 law banned 19 Islamist media in 2015, leaving Islamists little room to propagate their anti-Pancasila discourses. By 2018, the diminishing role of Islamist media provided an opening for moderate Islamic media to enhance their public profile. As a result, moderate Islamic discourses began to reign the Indonesian public sphere.

As the Islamists retreated, the Jokowi administration has gained the leeway to restore Pancasila’s legitimacy. Jokowi was right when he said in his June 1 speech that the government should be more creative in promoting Pancasila to contain the spread of radicalism in cyberspace.

However, it remains to be seen if the Jokowi government has effectively tackled the anti-Pancasila threat. A 2018 LSI survey shows that 13.2 percent of respondents supported Islam instead of Pancasila as the state ideology, while a separate survey by the Center for Political Communication Studies (CPCS) showed that support for sharia rose slightly to 13.3 percent in 2020.

Several ministries have been known to mobilize “buzzer” (influencers) to promote their programs, and there is a chance that this model will be replicated to promote Pancasila.

Eventually, the government will need the support of mainstream, moderate Islam organizations like the Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah to restore Pancasila as the state ideology. The country’s two largest Muslim groups have abundant human resources that can devise creative and persuasive social media campaigns in place of the government’s dull, indoctrinating approach.

Involving the two mass organizations is crucial to boosting the legitimacy of the government’s messages on Pancasila.

***

The writer is a visiting fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore, and author of The State and Religious Violence in Indonesia: Minority Faiths and Vigilantism