Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDiaspora community celebrates Indonesia 'Down Under'

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

"The motherland" still holds a special place in the hearts of its diaspora community, with some Indonesians maintaining a fierce sense of national and cultural pride, even after decades of living abroad.

It was 1981 when Tiur Ratu Munthe moved to Australia and settled there with her family. They made the move following racially motivated political upheaval that her husband, a Chinese-Indonesian, had experienced in 1974.

But even after years of living in the “Land Down Under” and despite the racism they experienced in Indonesia, Tiur is still proud of her Indonesian origin.

“Although I’ve lived in Australia for almost half a century, I still hold on to my Indonesian culture. It’s far, but it’s still in my heart,” said 70-year-old Tiur, who is of Batak ethnicity.

According to Statistics Indonesia (BPS), around 9 million Indonesians were living abroad as of September 2021. Members of the Indonesian diaspora are sometimes thought of as having lost their sense of nationalism. However, some individuals prove that the opposite is true.

Homesickness

Indonesia’s diverse cultures are what Tiur misses the most. She found that the Indonesian diaspora community in Australia has grown over the last 15-20 years, and that this has helped her cope with homesickness.

“The [diaspora] community has a vital role for me. It means we can preserve and eventually pass [our cultures] down to the next generation. For example, right after a funeral, we have a tradition called mangapuli, in which we visit someone’s house to console the family,” said Tiur.

Frans Simarmata, who has been living in Sydney since 1999, has a similar experience, emphasizing that the Indonesian tradition of gotong royong (mutual cooperation) is irreplaceable.

“In a more individualistic environment, it’s different: You are completely your own. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, you can easily get along with your peers at work,” said Frans, who works at a government office in Randwick, in New South Wales.

Harry Suharto says he misses his family. The retiree has lived over 53 years in the South Australia capital of Adelaide, with his wife Ursula Kusmardiarti as his only companion. With no siblings or other relatives in Australia, he believes that people who want to live abroad should be ready to be more independent.

“Cousins are one of the few things that you can’t have [here],” Harry said. He added that simple things like listening to songs by pop stars Titiek Puspa and Ayu Ting-Ting had helped him cope with homesickness.

“That’s the best entertainment I have so far,” Harry said, laughing.

On a more serious note, he said that members of the first-generation diaspora would always have a special bond with Indonesia, where they were born and raised in a culture and environment that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

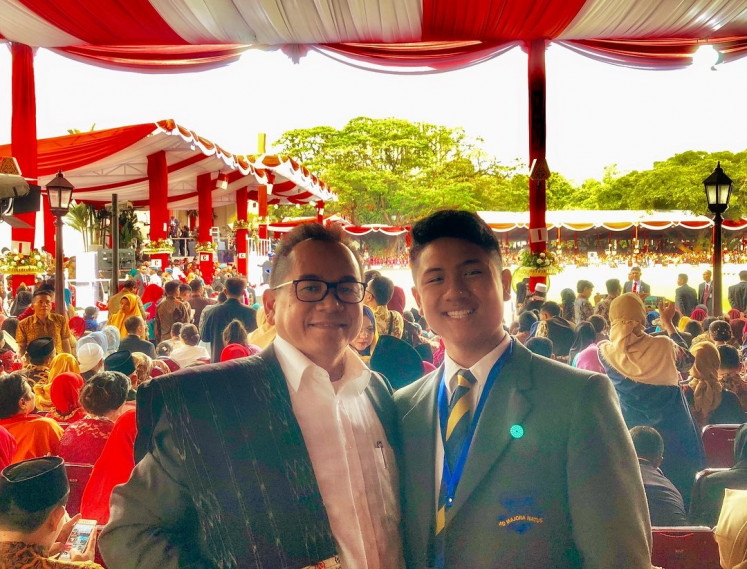

Culture: Frans Simarmata (left) and his son Xavier Simarmata (right) attend the Independence Day of Indonesia in 2018 at Merdeka Palace, Jakarta. Attending Indonesia’s cultural events is one of the ways Frans teaches his children about being nationalist. (Courtesy of Frans Simarmata) (Courtesy of Frans Simarmata/Courtesy of Frans Simarmata)Indonesian cuisine is also something members of the diaspora say they miss the most. With its thousands of different ethnic groups, the archipelagic nation is a culinary melting pot.

“Pempek [fish cake] from Jambi or gudeg [stewed young jackfruit] from Yogyakarta is some things I miss the most,” said Sastra Wijaya, a journalist who currently resides in Melbourne, reminiscing about his time studying at Yogyakarta’s Gadjah Mada University.

“I always buy canned gudeg from Yogyakarta and bring it back to Melbourne,” he added.

Giving back

Tiur preserves and passes down the Batak culture to her grandchildren by teaching them Batak dances. Dancing reminds Tiur of her childhood, when she performed during cultural festivals and church events in Jakarta.

She also contributes to her home country as an active member of Komunitas Merah Putih Australia (KMPA), meaning the Australian red-and-white community in reference to the colors of the national flag. The KMPA focuses on helping Indonesians in rural areas back home, and one of its activities involves managing water supplies in collaboration with local communities.

“It’s more important to be a proactive member of [Indonesian] society, even if you live far from the country,” said Tiur, who is also the head of the Batak Bonapasogit Sydney community.

Meanwhile, Sastra said taking frequent trips back home was a must.

“Of course, visiting your motherland will offer different closure. There are small developments that we’ll recognize only if we experience them ourselves,” he said.

Sastra added that there were many ways for the diaspora to show their appreciation for their homeland, such as by opening an Indonesian restaurant, holding a cultural festival or simply making achievements that could make the country proud.

Harry held a similar view, noting that being Indonesian was more than just holding a green passport.

Harry is a cofounder of the annual Adelaide Indonesian Festival, which celebrates Indonesian cultures.

He pitched the idea for the festival in 2008 after realizing that Australia did not have many festivals that introduced Indonesian culture.

“I remember there were only four to five stands, but thousands of Australians came, and I was so proud,” he recalled about the inaugural festival.

Harry’s daughter Ade Suharto is also involved in activities that promote Indonesian culture. A dancer, Ade creates performances infused with Javanese culture, which has made Harry very proud.

“You see, there’s always a piece of Indonesia. My wife was born in Java, she speaks Javanese. We [brought] the culture to our house here in Australia,” he said.

'Special bond': Harry (far right) shares that the first generation of the diasporas will always have a special bond with the motherland, as they were born and raised with the culture and the environment that they couldn’t find it anywhere else. (Courtesy of Harry Suharto) (Courtesy of Harry Suharto/Courtesy of Harry Suharto)Redefining nationalism

Sastra said Indonesians who had changed their citizenship should not be derided, especially if they continued to play an active role in promoting the country’s culture, whether publicly or privately. Many held dual citizenship because this made it easier to obtain Australian documents.

“Some [members of the diaspora] wanted to help communities in Indonesia, but they had difficulty accessing their bank accounts. After all, what’s the purpose of citizenship if you do not care about the country?” he said.

Frans added that the first-generation diaspora had a role in teaching their cultures to the next generations. One example was the proper way to address an elder in a greeting, “which I don’t find in other cultures”, he said.

“After all, we all need a sense of belonging, so no matter where we are, Indonesia is always a part of us,” Frans said.

“The farther away we are from our families, the motherland, [our] sense of belonging could be even more intense instead, since that’s the only way we come to an awareness that there are things we take for granted,” he added.