Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIndonesia exiles skeptical of rights restoration scheme

For the past few months, the government has been devising a scheme to reinstate the rights of political exiles who were rendered stateless after the Sept. 30, 1965, abortive coup blamed on the now-defunct and outlawed Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Nur Janti

The Jakarta Post/Jakarta

Overseas Indonesian students who were stripped of their citizenship during the 1965 communist purge are wary of joining a program intended to clear their names and restore their legal status nearly 60 years after the fact, especially as some still face ill treatment over their connection to the dark chapter of Indonesian history.

For the past few months, the government has been devising a scheme to reinstate the rights of political exiles who were rendered stateless after the Sept. 30, 1965, abortive coup blamed on the now-defunct and outlawed Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

At the time, hundreds of thousands of people traveling or living abroad were accused of being Indonesian leftists and were barred from returning to their homeland, even those who were studying on scholarships provided by the then-Sukarno administration.

Now, faced with the opportunity to return and have their rights restored in full, some exiles have said the government must set the record straight before they consider the offer, partially to prevent similar violations from happening in the future.

Sri Ningsih, 77, who was studying in Eastern Europe when the communist purge began, said that in order to clear their names, the government first had to be honest about how Indonesians living abroad came to be stateless.

She noted that revising the state version Indonesia’s history to acknowledge the realities of the period’s human rights violations was one of 11 recommendations submitted by a nonjudicial settlement team on past rights atrocities in January.

“We cannot set the record straight without revealing the truth,” Ningsih told The Jakarta Post last week.

The state disenfranchised many like her, who, because of their real or supposed links to leftist groups, had their citizenship documents revoked by the government.

Ningsih said she was among the few fortunate enough to be granted citizenship her place of residence at the time, Germany.

Another former student, Tom Ilyas, 85, who is now a Swedish citizen, demanded that the government work on preventing similar incidents from occurring in the future. That, he said, involved resolving past violations.

“I don’t know how the government can guarantee success in preventing [future rights violations] if not a single past case is resolved fairly,” he told the Post recently.

Ilyas was studying agriculture engineering at a university in China during the purge and was not able to return home after the Indonesian mission in Beijing confiscated his passport.

More recently, he was subjected to ill treatment when he visited his parents’ grave in West Sumatra’s South Pesisir regency in 2015, half a century after the bloody tragedy.

The region’s lingering anticommunist sentiment led to his arbitrary arrest by the local police and the confiscation of his Swedish passport. He was later deported and unable to visit Indonesia for about a year, he said.

In light of this experience, Ilyas questioned the government’s ability to fully restore the rights of political exiles without acknowledging the truth of the nation’s history or working to rid Indonesia of the anticommunist sentiment responsible for both the 1965 tragedy and the continuing persecution of its victims.

“As long as people’s mindset toward victims and their families hasn’t changed, I feel safer holding a Swedish passport,” he said.

Policy-making

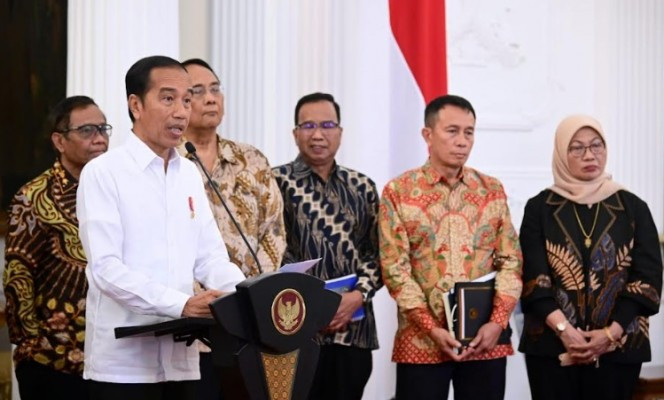

On Jan. 11, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo publicly acknowledged and expressed regret on behalf of the state for a dozen instances of past rights violations.

He pledged to provide restitution for victims and their families “without negating the judicial resolution” and declared that they had never betrayed the country. But the government has since sought to settle the issue without bringing the perpetrators to court.

On May 2, Coordinating Political, Legal and Security Affairs Minister Mahfud MD said the state would focus on restoring the rights of victims and leave any judicial settlements to the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) and House of Representatives lawmakers.

The Law and Human Rights Ministry is currently drafting policies to accommodate political exiles who are willing to have their citizenship restored or return to Indonesia. The program is scheduled to launch in June.

The ministry’s acting director general for human rights, Dhahana Putra, said officials had a new estimate of how many people would be eligible for the program but added that the data was still being verified by the Foreign Ministry.

“The Law and Human Rights Ministry will provide priority citizenship services for [political exiles] that have been verified by the Foreign Ministry. [Currently,] there are about 117 exiles from after the 1965 incident,” Dhahana told the Post on Sunday.

It is difficult to ascertain the precise number of Indonesian political exiles living overseas. Many have died, and those who are still alive may have adopted foreign nationalities and identities. As Indonesia does not recognize dual citizenship, some have also voluntarily renounced their Indonesian citizenship for that of another country.