Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

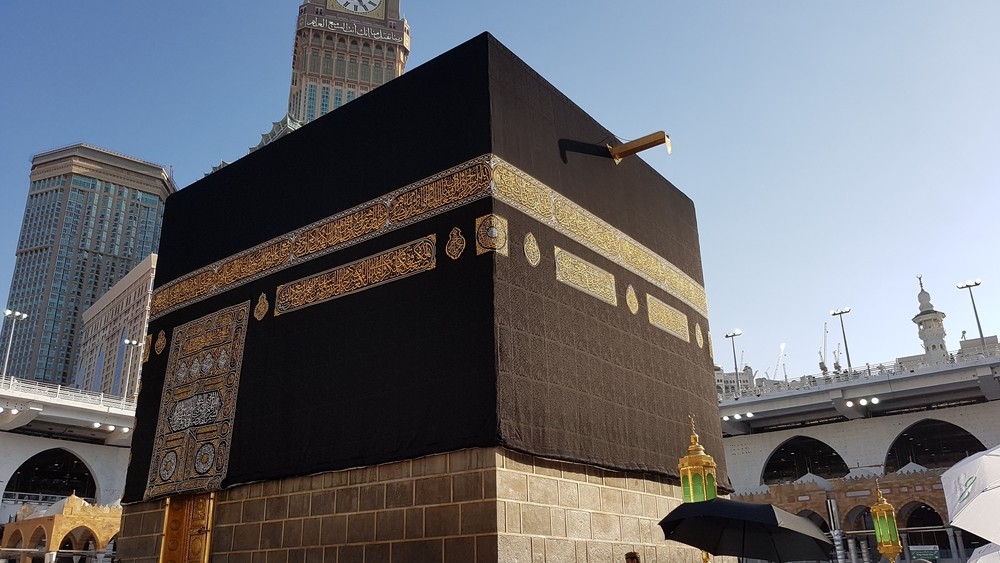

View all search resultsHigh demand for symbols drive 'Islamic' black market

The need of religious symbols among Indonesian Muslims today is much bigger than ever. The striking contrast between the present situation and the past is stunning.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he Islamic black market is spreading in various forms. By playing around with Islamic symbols in separate cases, First Travel, Abu Tours and Kanjeng Dimas (the cleric who many believed could magically multiply their money) scammed trillions of rupiah over the years out of consumers across the country.

There have also been unqualified Muslim preachers arbitrarily offering troubling interpretations of Islamic teachings on television, like the claim that heavenly pleasure is nothing more than an orgy. A popular female Muslim TV preacher turned out to be incapable of writing Quranic verses in proper Arabic script. Muslim hard-line groups such as Jama’ah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia, Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia and others aggressively propagate the necessity of sharia through the establishment of an Islamic state.

Recently, a series of terrorist attacks took dozens of lives in Depok, Pekanbaru in Riau and Surabaya; the horror in the last city was even committed by parents as suicide bombers and their children. These are tips of a bigger “Islamic black market” iceberg. Why is it spreading?

Obviously, religion is a symbolic system, as the anthropologist Clifford Geertz explained. However, the need of religious symbols among Indonesian Muslims today is much bigger than ever. The striking contrast between the present situation and the past is stunning.

Until the mid-1980s, due to the New Order’s hostile political stance, Indonesian Muslims were marginalized and often seen as obstacles, if not the government enemy. In the scholar Nurcholish Madjid’s terms, Muslims were known as “a majority with a minority mentality”. When possible, most Muslims tended to avoid using Islamic symbols in public spaces, let alone go to work in headscarves (for women). Even saying assalamu’alaikum (peace be upon you) to greet a mixed audience made many Muslims feel awkward.

Since Suharto reached out to Muslims in the late 1980s, we have seen the surge of the “Islamic wave” along with new freedoms.

Today, it is even “normal” for non-Muslims to say assalamu’alaikum in official meetings. Many public schools unofficially require female Muslim students to wear the headscarf as part of their school uniform. To gain public sympathy, more female Muslims, from street beggars to mega-graft convicts, wear the hijab. Only recently, the government of Aceh Besar regency issued a bylaw requiring all flight attendants to wear the hijab whenever their plane landed there.

Unlike in the past, since the 1990s Islam has become a powerful presence. When everyone uses a smartphone, not using it will make you look stupid. When most Muslims take on all kind of Islamic attributes and symbols, those who do not participate look ugly, even despicable and alienated.

Today there is greater social pressure requiring Muslims to demonstrate their religious identity. Therefore, “Islamic” fashion, cuisine, school, media, forums, associations, groups, banking, business etc are growing everywhere. Islamic symbols have become valuable resources, precious capital, marketable commodities and a defining identity readily available for different purposes.

Besides spirituality, religion is a social practice, as observed by the scholar Pierre Bourdieu. Hence, the growing demand for religious symbols has opened up greater opportunities for political, economic and social interests.

Meanwhile, due to rapid change, “religious providers” cannot always properly cater to all the demands. For instance, during Ramadhan, religious events are held simultaneously across mosques, institutions and forums, dramatically increasing the demand for Muslim preachers or speakers. So does the demand for various needs supposedly required for a proper “Islamic” life style.

When social pressure for religious symbols is so high compared to limited capacity of “religious providers” — especially when combined with insufficient religious literacy — the essence and quality of religious practice become secondary. People just need to look normal by participating in the common practice of “going Islamic” to avoid being alienated from their group. This thirst for religious symbols eventually invites new actors, many without proper training, some even with dark motives.

It is exactly this big gap between the supply and demand of Islamic symbols that has helped created the Islamic black market, a free space for quasireligiosity, pseudo-Muslim preachers, fake Islamic business and religious fraud like the one committed by First Travel and Abu Tours, as well as teaching hoaxes, including radicalism and terrorism.

Illegal and fake products are exchanged and unregulated in this space called the Islamic black market. What looks convincing and real on the surface to uninformed eyes can be totally bogus, even poisonous.

This black market mostly provides “selfie religiosity” — attributes for exclusive personal piety that serve the interest of politicians, businesses or other profit seekers who have nothing to do with spiritual matters. Even worse, the Islamic black market is also fertile ground for religious radicalism and terrorism.

The wide reach of the Islamic black market explains the puzzling discrepancy between over-religionization of public life, where Islamic symbols and attributes are strongly visible on the one hand, and the pervasive ethical problems on the other, such as the increasing numbers of graft cases, frequent violations of human rights, poor interreligious relations and even violence in the name of religion.

Although reality has shifted fundamentally in comparison to the 1980s, and with Islam predominant on every level, some Muslims are still entrapped in the old “minority mentality”. They are always anxious to have a bigger share and worried about being marginalized. As a result, some Muslims are hypersensitive when their group’s interests are at stake. Any minor issue, like the case of Sukmawati Soekarnoputri’s poem, is perceived as religious blasphemy.

Sadly, when it is about the rights of others, these grumpy Muslims are very insensitive. In addition to the Aceh local regulation on headscarves for all flight attendants, the banning of community service to be held by St. Paul church of Yogyakarta and persecution against the Shiites and the Ahmadis are among notable examples.

It’s as if it is taken for granted that the majority has the privilege to define the other, but not vice versa. Whenever people pay too much attention to religious symbols, they will easily misrecognize the true meaning of religion.

Since religion is a symbolic system, obviously religious symbols are very important. However, religion should not be locked up into symbolism. If religion is to play a significant role in taking up the challenge faced by the people, we should stop making religion part of the problem.

Religion should be part of the solution. We should bring back religion to its primary function, namely as moral guidance and ethical foundation for its adherents.

In fact, Islam encourages Muslims to embrace and to cooperate with all human beings in creating a just and peaceful world for all. Therefore, exclusive symbolic personal piety should be transformed into liberating social ethics and inclusive public morality.

Otherwise, the Islamic black market may spread even wider and more people will fall prey to it.

***

The writer lectures at the Department of Intercultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University (UGM), Yogyakarta.