Srihadi Soedarsono and his contribution to Jakarta's skyline

His piece is a kind of social commentary on a period in Jakarta’s history.

Change Size

Srihadi Soedarsono (JP/Dylan Amirio)

Srihadi Soedarsono (JP/Dylan Amirio)

A

t 86 years of age, veteran painter Srihadi Soedarsono shows no signs of slowing down, even after amassing decades of experience and global recognition for his quintessentially Indonesian subjects that warmly grace his canvases.

Spending most of his creative time at his studio in Bandung, Srihadi is preparing for his latest exhibition where he will showcase three of his most socially significant works: two of which hold background stories that indirectly helped change Jakarta’s skyline.

Ja(YA)Karta will be the veteran painter’s newest exhibition.

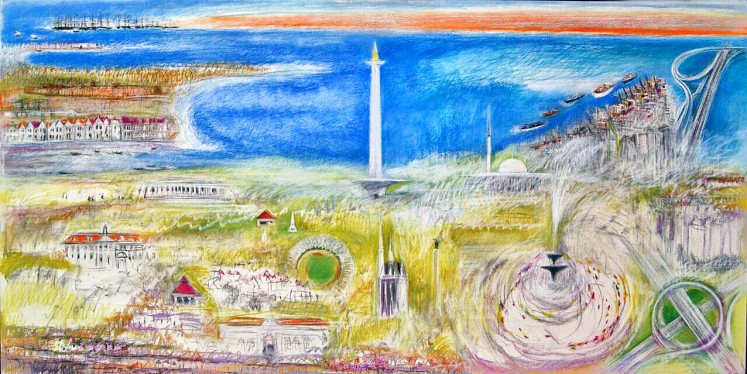

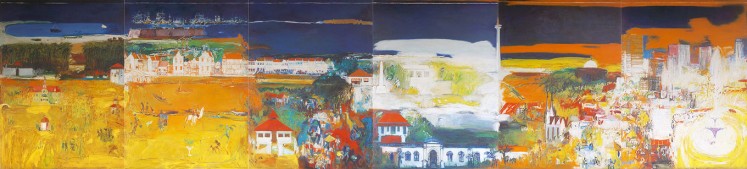

Held at the Jakarta Fine Arts and Ceramics Museum in West Jakarta from Aug. 24 onwards, the main centerpiece of this exhibition will be Jayakarta, the six glorious panels measuring 275x1,200 cm oil on canvas painting, which Srihadi painted in 1975 and which was once on display at City Hall on Jl. Medan Merdeka Selatan in Central Jakarta.

The exhibition’s curator, Maya Sujatmiko, described the piece as a kind of social commentary on a period in Jakarta’s history where infrastructure development had started to take off following the liberalization of the country’s economy in the 1970s.

The origin of Jayakarta, as explained by Srihadi himself, came about from an emotional reaction from Jakarta’s top authorities in the 1970s toward a previous painting of his.

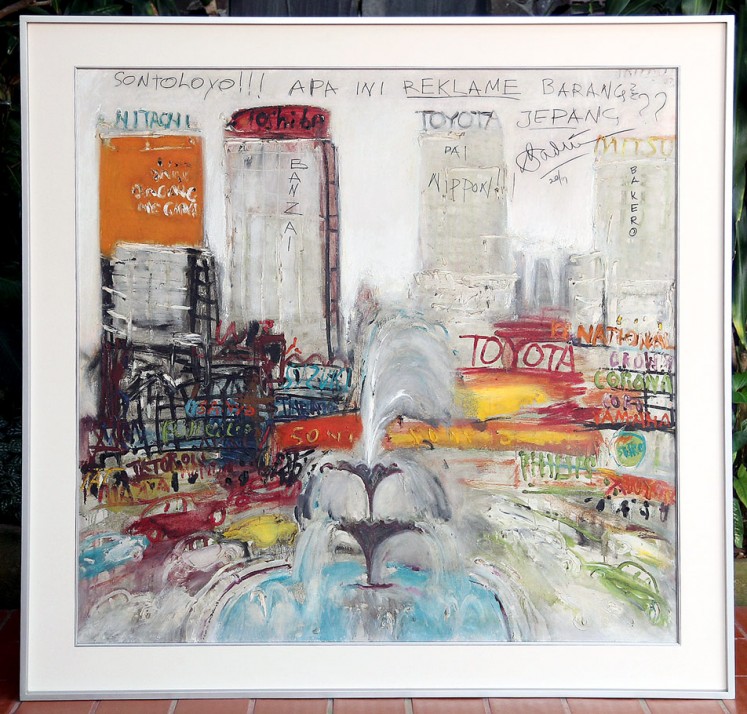

The year was 1975 and a painting by Srihadi made in 1973 entitled Air Mancar, a slightly wavy and impressionistic take on the Thamrin skyline from the perspective of the fountain roundabout nearby Monas, was prepared for display at the opening of the Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (TMII)’s main pavilion.

The painting was noted for its grey sky nestled above Jakarta’s obscured buildings, most of which were lit mainly by neon billboards bearing the names of major Japanese companies.

For Srihadi, the myriad of bright neon lights bearing the names of Japanese companies such as National, Toyota and Hitachi were eyesores dotting an otherwise adequate Thamrin skyline, but nonetheless he painted the skyline as it was because he wanted to show the skyline in its reality.

The presentation of bleakness in his painting caught the attention of then Jakarta governor Ali Sadikin.

“When Ali saw that painting for the first time at the opening of the Taman Mini Indonesia Indah [TMII] pavilion, he seemed offended by it. He took a marker to write what he thought about the painting directly on the canvas […] and signed it!” Srihadi recalled.

Ali wrote: “Sontoloyo!!! Apa ini reklame barang2 Jepang??” (Silly! Is this an ad for Japanese companies?)

Ali would later apologize to the painter after taking a spontaneous drive around Thamrin that same night with literary figure Ajip Rosidi and cultural commentator Ilen Surianegara to gain an artistic viewpoint on the situation. He changed his mind after reportedly asking one of the experts, “Is my city really as ugly as Srihadi’s painting?”

Srihadi understood that Ali’s perception of the city lights was different to his.

“He might have thought that the bright lights were a good thing for Jakartans; like a symbol of modernity. But he also understood that art is all a matter of perspective,” he said.

Spurred mainly by the Malari demonstrations of 1974, which opposed the grip of Japanese companies on the Indonesian economy, Jakarta gradually cut down the number of Japanese billboards along the city’s main thoroughfares over the succeeding years.

Afterwards, Ali commissioned Srihadi to paint a less bleak, but grander vision of Jakarta for display at City Hall: a painting that should define the city’s beauty. And thus was born Jayakarta.

Meanwhile, Srihadi said the Air Mancar painting vanished not long after its premiere, and he did not get his hands back on it until 2002 when he tracked down one of Ali’s subordinates, who took the painting from a storage area in City Hall in order to “protect it from further harm.”

“I received the painting in its pristine, unscathed condition. I cannot tell you how glad I was when that painting fell again into my hands. It was a relief knowing that it was still alive and safe,” he said.

Air Mancar will be one of the three paintings to be displayed at the Ja(YA)karta exhibition.

When asked about the state of the Thamrin skyline today, Srihadi chuckles. Despite giving no comment, he expressed his optimism that the country’s younger generation of artists would offer some social commentary.

“I can’t do and feel things as a 20-year-old does anymore,” the artist said as he laughed.

“Commentary on the current generation should be done by the young, because they’re the ones who understand [this era] the most.”