Martin Aleida: Voicing unheard voices

While backpacking across Europe to meet Indonesians living in exile, author Martin Aleida discovered that even though they may no longer live in Indonesia, the country remains in their hearts.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Painful past: Martin Aleida gives a testimony at the International People´s Tribunal in The Hague in November 2015. (Youtube.com/File)

Painful past: Martin Aleida gives a testimony at the International People´s Tribunal in The Hague in November 2015. (Youtube.com/File)

W

riter Martin Aleida was surprised when members of the ASEAN Literary Festival (ALF) committee apologized to him for the absence of a photograph of writers from left-leaning artist group Lekra, in a room where he was a speaker in a discussion.

Prior to that day, an audience member asked for his comment about the absence of a photograph of Lekra writers in the room that ALF used to pay tribute to the country’s prominent writers by displaying their photographs on the wall.

“In this digital era, you cannot be fooled. You can Google,” he simply answered. “You have to know that [Lekra activist] Pramoedya Ananta Toer was nominated many times to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.”

Martin, however, does not blame young people if they do not know about Lekra’s artists, because during the authoritarian New Order regime, Indonesia’s second president Soeharto banned their names from appearing in school textbooks after the G30S/PKI tragedy.

On Sept. 30, 1965, six high-ranking army generals were murdered. The tragedy led to a communist purge that claimed the lives of more than 500,000 people affiliated with the now-defunct Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

His close friend arrested Martin in 1966 for his affiliation with Lekra, which was associated with the PKI. However, he was not tortured and was released in less than a year.

He bore witness to the arrest at the International People’s Tribunal on the 1965 Crimes against Humanity in Indonesia (IPT 1965) in November 2015 in the Netherlands, which many elderly exiles attended.

Martin said that as of today, he observed that many people had yet to understand the differences between socialism, communism and atheism.

When he decided to attend IPT 1965, no one tried to stop him. However, his fellow writers, including Taufik Ismail, criticized him. “When he [Taufik] talked about the 1965 tragedy, he talked about massacres in the Soviet Union and Cambodia. He did not talk about what happened here because he supported the regime that committed the massacre,” Martin said.

The author was awarded the title of this year’s best short story for his work Tanah Air (Homeland), which tells the story of an exile’s wife who committed suicide, published in Kompas daily in June.

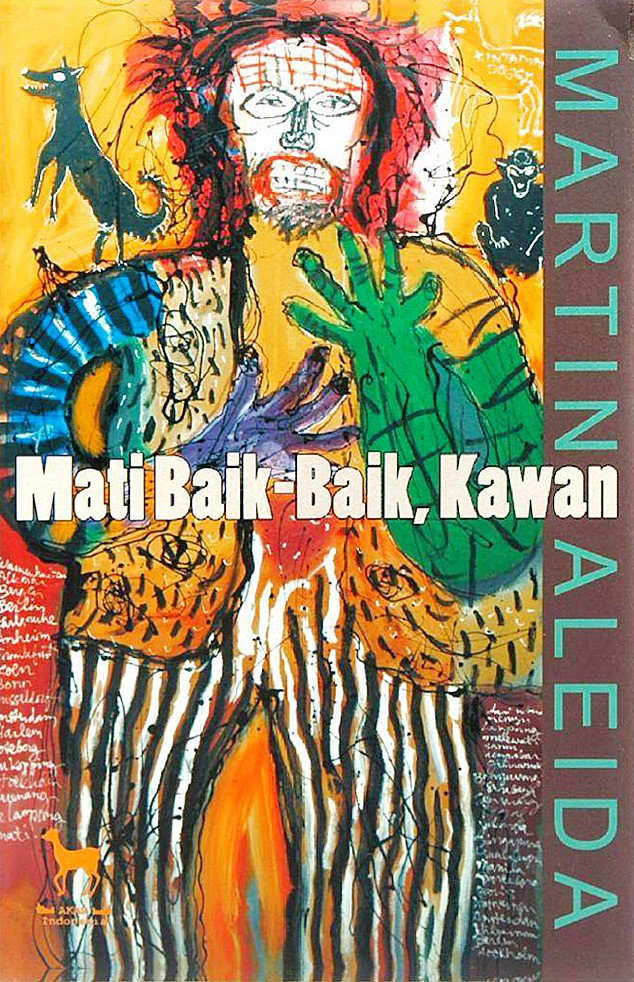

In August, the 73-year-old released a new book, Tanah Air Yang Hilang(Missing Homeland).

“This book collects the stories of 19 Indonesians who were forced to lose their homeland. After the G30S/PKI incident, their passports were revoked so they had to find new homelands,” he said.

To make the book, Martin backpacked from March to May 2016 from the Netherlands to Germany, Bulgaria, France and the Czech Republic to interview over 30 exiles.

“I stayed at Chalik Hamid’s house in the Netherlands. I did not need to pay him, but he asked me not to forget to feed his fish in his aquarium,” he says.

Originally from Medan, North Sumatra, Chalik was studying in Albania when the 1965 incident happened. After the tragedy, he could not go home while his wife was sent to Buru Island in Maluku for being a member of the Indonesian Women’s Movement (Gerwani), the female wing of the PKI.

In Prague, Martin met Charles University lecturer Soejono Soegeng Pangestu, a 77-year-old Indonesian who has lived in the Czech Republic since 1963.

After the 1965 tragedy, the embassy summoned all university students, including Soejono, and asked whether they supported the New Order regime. Learning that human rights violations had happened in Indonesia, he said no.

Because of his answer, Soejono was branded a communist.

Like Soejono, I Ketut Putera also supported president Sukarno, a stance that made the New Order regime revoke his passport in 1967 while he was studying economics in Bulgaria.

In Sofia, Martin interviewed Putera, 76, who has worked for the Bulgarian Foreign Ministry for 23 years. During 32 years of the New Order regime, he was never allowed to set foot in the Indonesian Embassy in Bulgaria.

Putera is a big fan of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo because during the anniversary of Indonesia’s Independence Day in 2015, he was not only invited to the embassy, but also given the first slice of tumpeng (cone-shaped rice dish) as the oldest Indonesian in Bulgaria.

In the Netherlands, Martin met Dharmawan Isaak, who was the rector of Institut Ilmu Pertanian (Agriculture Institute), a Cisarua-based research center which PKI leader D.N. Aidit reportedly often visited.

Dharmawan, who was already in China in 1965, lost not only his wife, who was forced to marry another man, but also his 9-year-old daughter, who committed suicide after learning that her father could not return home because the government had revoked his passport.

In France, Martin met Nita, the daughter of Sobron Aidit, the younger brother of D.N. Aidit. In 1965, her father worked at Peking University, teaching Indonesian literature.

In 1981, they moved to France and set up an Indonesian food restaurant in Paris, which recently received an award from influential French restaurant guide Gault et Millau.

Martin said the idea to interview Indonesian exiles first came to his mind in 1976 after he covered the launch of Indonesia’s first satellite in Florida, in the United States.

However, he finally realized his plan after testifying at IPT 1965. At that time, he felt touched when he witnessed two exiles bear witness behind a black screen to hide their faces.

Martin did not know the exiles’ reasons, but he assumed they were traumatized and worried about the impacts of their statements to their family members in Indonesia, something he defined as the New Order regime’s success in stigmatizing anyone allegedly affiliated with the PKI.

“This country, including its dignity, was wrecked by the New Order,” he said.