Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA meaningful visit, or another ceremonial trip to Papua?

Since becoming part of Indonesia through the deeply flawed process called the Act of Free Choice, facilitated by the UN in 1969, Papua has been treated relatively inappropriately by the government and many Indonesians — through inefficient policies, an intensive security approach and racial prejudice.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

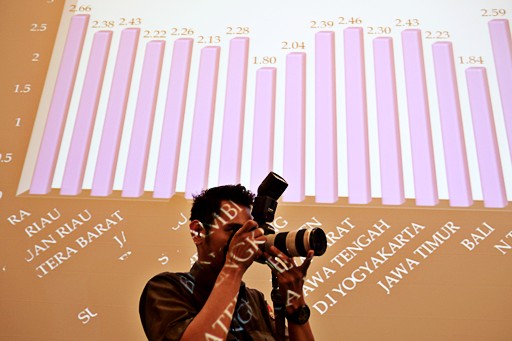

In focus: A photojournalist takes his place in front of a screen showing an election-related violence index compiled by the Election Supervisory Agency (Bawaslu) ahead of the simultaneous local elections on Dec. 9. General Elections Commission (KPU) chairman Husni Kamil Manik said the noken voting system would be still used in 2017 regional elections in Papua

(thejakartapost.com/DON)

In focus: A photojournalist takes his place in front of a screen showing an election-related violence index compiled by the Election Supervisory Agency (Bawaslu) ahead of the simultaneous local elections on Dec. 9. General Elections Commission (KPU) chairman Husni Kamil Manik said the noken voting system would be still used in 2017 regional elections in Papua

(thejakartapost.com/DON)

A

recent three-day visit by Coordinating Security, Legal and Security Affairs Minister Luhut Pandjaitan to Papua, Indonesia’s easternmost region, was noticeable for two reasons.

First, Papua is a priority for the administration and the visit of Luhut, one of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s trusted advisors, followed Jokowi’s own visits. We can thus imagine how important this visit is, not only for the central government but also for Papuans as a whole.

Second, Luhut’s visit showed a strong commitment to overseeing that all policies are undertaken appropriately, particularly since the special autonomy law has been widely criticized as ineffective for improving Papuans’ welfare.

However Luhut’s visit was no more than symbolic, rather than being truly meaningful for the powerless indigenous people. The key issue is the extent to which Luhut’s visit can thoroughly address the fundamental concern of Papuans, namely genuine trust.

Since becoming part of Indonesia through the deeply flawed process called the Act of Free Choice, facilitated by the UN in 1969, Papua has been treated relatively inappropriately by the government and many Indonesians — through inefficient policies, an intensive security approach and racial prejudice.

This treatment has led to distrust and limited sympathy among Papuans toward the Indonesian government and fellow citizens in the western parts of the country.

Thus, a visit by such an important figure stimulated more skepticism than optimism among the indigenous people.

Luhut’s visit failed to highlight one fundamental problem of Papua: Its political status since it became part of Indonesia. He preferred to discuss more about the progress of developmental programs with Papuan stakeholders, including the building of Post Limit Cross Country Skouw on the border between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea (PNG).

However, the more he avoided talking about political problems in Papua, chiefly the aspirations for independence, the more the government showed to the international community its incapability for handling the ethnic-based conflict.

The concept of dialogue, which many have repeatedly asserted to be an important step toward resolving long overdue problems in Papua, did not receive the minister’s attention.

Luhut also visited PNG and Fiji, two supporters of Indonesia regarding the Papuan issue in the Pacific.

Through ad hoc economic aid and bilateral agreements with PNG and Fiji, the main objective of that trip was most likely to defuse the Papuan issue in the Pacific, particularly the role of the United Liberation Movement of West Papua (ULMWP) in the Melanesian Spearhead Group, an economic group that granted observer status to the ULMWP in 2015.

By providing such support, Indonesia hopes these two countries can either contain the Papuan issue or keep it from becoming one of the central political themes in the Pacific.

In the security sphere, there was no endeavor for a breakthrough during Luhut’s trip to Papua. As a former army general and given his current position related to security matters, he was expected to tackle one of the most contentious issues in Papua, particularly regarding initiatives to build a new army territorial command in Manokwari and a police brigade headquarters in Wamena — not to mention the so-called joint expedition, dominated by 670 military personnel, including the Army’s Special Forces (Kopassus), and civilians, aimed at conducting research and collecting data on Papua’s natural resources and its people.

This research activity is at odds with its primary duties as stated in the 2004 Indonesian Military Law. Instead, Luhut merely promised to resolve past human rights cases in Papua, without details.

This is largely lip service since two prominent cases during the past two years, namely those of Paniai in 2014 and Timika in 2015, remain unresolved.

Neither did Luhut’s visit address the contentious massive investments across the area. Investment-driven policies have been widely criticized for failing to improve Papuans’ quality of life since the area became an Indonesian province. Many giant private investors — mostly in oil palm plantations and agricultural projects — have been exploiting many local forests based on their concessions.

Migration was another issue overlooked by the minister’s official trip to Papua. According to the 2014 report of the Justice and Peace Secretariat of the Jayapura Bishopric Mission, huge numbers of people transmigrating on a daily basis have negatively affected the indigenous population in the cultural, political and economic spheres.

This has led to ceaseless conflicts between the settlers and the indigenous people.

Moreover, without discussing all of these crucial issues, Luhut’s visit casts doubt on how the government handles the area and most importantly how it builds trust among Papuans toward Jakarta.

Accordingly, his visit will be seen by Papuans as another ceremonial activity by officials rather than a genuine and meaningful gesture of reaching out. All in all, Luhut’s trip to Papua remains merely symbolic for many indigenous people.

***

The writer is a researcher at the Marthinus Academy, Jakarta.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com.