Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRunning a polling station - How hard could it be?

I ran a polling station in South Jakarta along with a retired banker, a small-time businessman, a housewife, a young IT worker, a parking attendant, a house helper and two neighborhood guards.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

s running a polling station in the April 17 general election was not all that complicated, the General Elections Commission (KPU) entrusted the job to volunteers, as has been the practice in previous elections.

This year, the KPU, the national agency responsible for organizing the elections, recruited more than 7.2 million people to help run 810,329 polling stations nationwide. Each was managed by nine ordinary citizens from diverse backgrounds recruited from neighborhoods. The job was simple: administer the votes, count the ballots afterwards and fill up the dozens of forms.

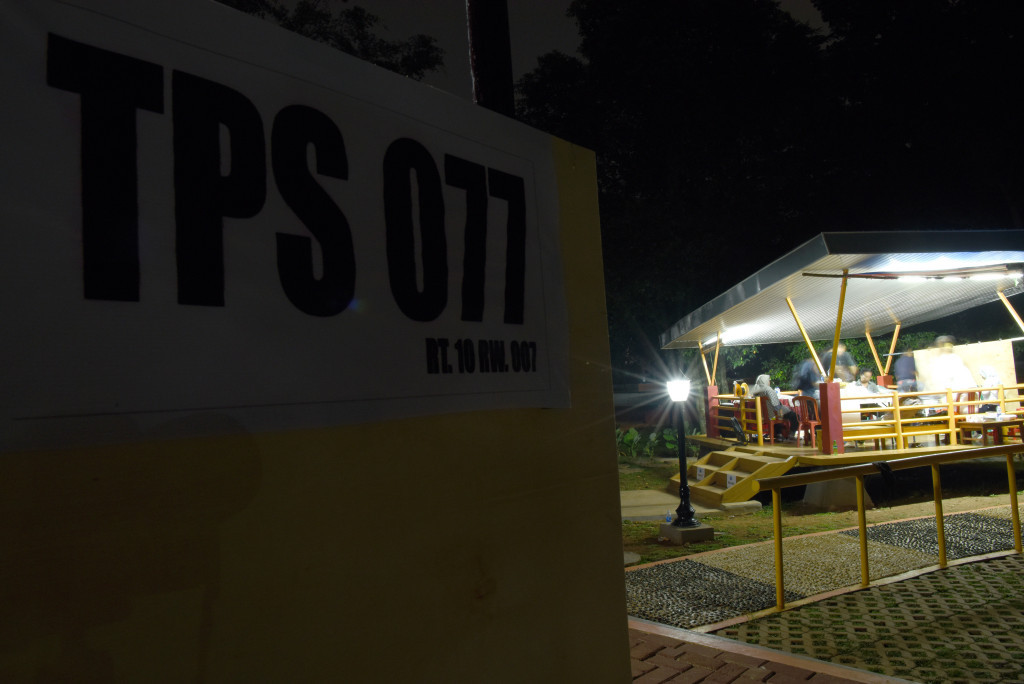

I ran one such station in South Jakarta along with a retired banker, a small-time businessman, a housewife, a young IT worker, a parking attendant, a house helper and two neighborhood guards.

It was a seemingly simple task, but running a polling station carried a huge responsibility requiring diligence. While we knew the rules about who has the right to vote, we were asked to be flexible since some people were not registered or did not receive the formal invitation to vote.

There was also the question of our integrity. Although we had our political preferences, it was important that we not let them affect how we work. Our neighbors, particularly the official witnesses assigned by political parties to our polling stations, were there to watch over us.

But here is the catch: Running a polling station was arduous, stressful and time consuming.

On the day, those running the polling stations put in an average of 20 hours of work. We turned up one hour or so before opening the polling stations at 7 a.m., and we were still counting the votes in the evening and filling in the forms when most everyone else had gone to sleep.

At my polling station, we finished at 2 a.m. the next day. But upon hearing that there was a long line of people from other polling stations trying to deliver the ballot boxes to the local KPU district office, we decided to take a nap first and delivered our boxes at 8 a.m.

A local poll administrator helps a voter insert ballots into the correct boxes on April 17 in Kemalang district in Klaten, Central Java. (JP/Magnus Hendratmo)It was sad but not all that surprising to hear that many volunteers died of exhaustion. Some news say as many as 20 died. Many of us have not recovered from exhaustion five days later.

Registering the votes and counting the ballots for up to 300 people — the maximum number of voters assigned to each polling station — may not seem like much. But each voter cast up to five ballots for the different elections (president/vice president, the House of Representatives, the Regional Representatives Council, the provincial-level local legislative council and the regency/city-level provincial council), so a polling station could end up registering up to 1,500 ballots.

Diligence was crucial. We had to account for every ballot used, unused and spoilt. We had to make sure that the number of votes cast was the same as the number of people who voted. It was not uncommon to find polling stations repeating the vote counting because the figures did not match.

It was not all administrative work as we also had to deal with people. Most voters were pretty easy to administer, since they were our neighbors whom we knew. But we did get the few difficult cases in which we had to make a decision, in consultation with the polling station supervisor and the official witnesses, to let voters cast their ballots even though they were not registered.

There was the case of a nurse from Flores Island who works in a South Jakarta hospital and resides in East Jakarta, who came to vote at our polling station. We would have accommodated her if she had a letter from the hospital stating that she was on duty on April 17. Apparently the hospital only gave her that one hour to take leave but no letter. She did not return.

There was the case of the wife of a neighbor who had an ID card from Sumatra. She insisted on voting upon producing her electronic ID-card. We turned her away in the absence of the official form, called the A5, stating that she intended to vote at our polling station. The KPU had been generous in extending the deadline for people to secure the A5 form up to one week before election day.

But we accommodated five people who were not registered but were able to produce their electronic ID cards showing that they lived in our district. These were people whom the KPU had, for technical reasons, failed to register. And we had six voters who came with the A5 form.

A man prepares polling station TPS 15 in Keraton district, Yogyakarta, on Tuesday. A red carpet was rolled out at the station, where a wood signpost emblazoned with the Javanese greeting "monggo" (welcome) was also set up. Yogyakarta Sultan Hamengkubuwono X and his family voted at the station during the country’s first simultaneous presidential and legislative elections on Wednesday. (The Jakarta Post/Tarko Sudiarno)Work for volunteers began long before April 17. These include registering voters in the neighborhood as long as a year ago. There were four rounds of re-registrations, each time updating the data of voters.

Volunteers were responsible for setting up polling stations that were accessible and convenient for voters, including voters with physical disabilities. The KPU gave Rp 1.6 million ($106) for logistics, a sum that barely covered the cost of renting a sizeable tent. We scrounged around for chairs and tables, with some of us forking over our own money, while some had the support of neighbors.

The KPU gave us a tiny stipend for honorariums and three meals for our work on April 17, but not before cutting it for sales and income taxes, even though we were not selling anything to the KPU and many volunteers had earnings far below the official taxable income.

Volunteering was never about the money, nor was it ever about helping our preferred candidates or parties win the elections. We were so busy on April 17 that we barely had time to follow the news about what was happening elsewhere in the country. Most of us were too focused on ensuring that we did our job as best as we could in the short time allotted to us.

Most of us volunteered our time and energy out of our sense of duty to the nation. Many of us were honored and proud to be part of this great project of making democracy work in Indonesia.