Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHow an ojek driver became entangled in a Thai ‘pig butchering’ scam, Pt. 1

Pig-butchering is a crypto scam that often depends on human trafficking.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Pig-butchering is a crypto scam that often depends on human trafficking.

This is part one of a two-part story.

Jaya was an ojek (motorcycle taxi driver). At 31 years of age, he moved from Jakarta to Malang, East Java, hoping for a better life along with the lower living cost there. He had always managed to survive on his own, such as by running his own drinking water refill service.

In the middle of 2021, Jaya, who asked to use a pseudonym for this story, decided to invest in an automated trading scheme after he saw an advertisement for it on social media. It turned out to be a scam, and the father of one lost some US$14,000. He was forced to borrow money from his close friends and work as an ojek driver to pay for his 6-year-old daughter's asthma treatment.

“I’ve been a nomad since I was 23 years old. I lived in Bali for five years, then moved to Malang for the past three years,” Jaya said.

“It’s just me and my own little family, my parents have passed away. Because of the cost of living and my daughter's condition, I chose to reside in a city like Malang,” the associate’s degree graduate in administration said.

Entangled in debt and his daughter's medical bills, Jaya saw another work opportunity on Facebook around early April 2022. The job offer seemed promising, a position in “sales marketing” at an investment company in Thailand. After his misfortune in investing, Jaya was eager for another chance, so he signed up for the job.

"It's hard to find a job at my age without a bachelor’s degree,” Jaya said.

Trafficked

On May 3, 2022, Jaya and two other Indonesians in their 30s and 40s traveled to Thailand to meet their future employer. Once they arrived in Thailand, they were brought to a dormitory.

Things immediately went wrong. Jaya recalled that a day after they arrived in Thailand, the employer ushered them into a minivan and drove them far from the glittering lights of Bangkok into the jungle. Jaya and two other men were asked to cross a river into Myanmar. It turned out they had been sent to Myanmar illegally to work for a fraudulent company known as KK Park. KK Park was run by Cambodian-Chinese businessman She Zhijiang.

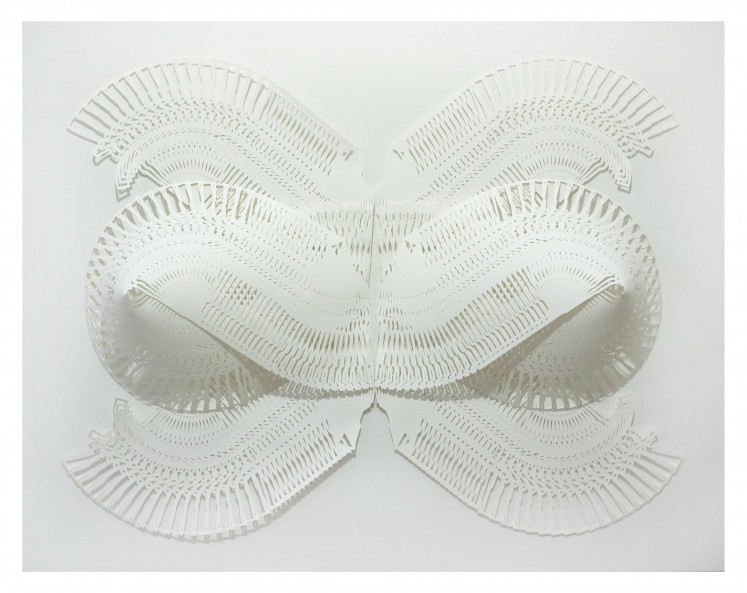

Wishing to come home: Migrant workers from Indonesia who fell victim to a job scam in Cambodia gather in a company dormitory in Sihanoukville City. (Kompas.id) (Kompas.id/.)Zhijiang was one of the most wanted criminals in China. He had been notoriously involved in other “pig-butchering” scams. Usually, in such scams, the scammers approach the victims and build trust by promising a large sum of money before cutting them off of, leaving the victims with nothing.

Reuters reported that Zhijiang had been on the run since 2012. The 40-year-old had been involved in illegal online gambling operations in Southeast Asia and was the chairman of Yatai International Holdings Group, which operated gaming investments in Cambodia and the Philippines. The company is known to have developed a $15 billion casino complex in Myanmar’s Karen State, Shwe Kokko.

Zhijiang was arrested on Aug. 15, 2022.

Daily, Jaya had to call dozens, even hundreds of strangers based in the United States. The syndicate typically targeted several characters: professional white-collar workers, philanthropically minded people and those who had lost loved ones.

Jaya and others were encouraged to build relationships with the targets. Often, Jaya and his coerced coworkers were made to start personal chats seeking to draw targets into emotional conversations. Simple phrases such as “have you eaten yet?” or “good morning” sought to evoke a sense of closeness.

Jaya would not be paid unless he could scam around $10,000 from the target. He could not go home either. If the workers wanted to go home, they needed to pay at least $22,500.

“I had no choice. We either continued working, or they would sell us to other traffickers,” Jaya said, adding that he had intended to go home in early June to check on his daughter in Malang.

Jaya was not the only one to fall prey to the scheme. Kompas reported that from April-July 2022, Migrant Care received complaints from several Indonesian migrant workers about fraudulent investment companies in Cambodia, the Philippines and Thailand. The Indonesian Embassy in Phnom Penh rescued 62 Indonesian workers stuck in such a scheme from Sihanoukville, Cambodia.

The former ojek driver described the compound as a living hell, noting that in a day, the employees needed to fill their quota of victims, and if they failed, they would receive military-style punishments. Employees had to do 100-300 push-ups, run for at least five laps or were left under the sun for one hour. In the worst cases, the failing employees ended up in what Jaya called a blood farm.

“I remembered they took my blood twice, even though it wasn't a huge amount of blood. They told me it was for a normal blood donation,” Jaya said.

Jaya and his fellow victims also had to work at least 15 hours a day.

Far from the $1,181.41 to $1,250.90 that the company had promised, the Jaya’s first paycheck was $421.70. It was for July, two months after he was trafficked.

“For the six months I spent there, I was only paid twice,” Jaya said.

He added that the employees could only use the toilet four times a day, for a maximum of seven minutes each. They were only allowed to have access to their cellphones for ten minutes to call their family.

Way home

“If you want to go home, first you need to get at least $1.5 million,” Jaya said, referring to the total amount required to be scammed.

If Jaya failed to get the $1.5 million for his employer, he needed to pay $12,000 for ransom, which seemed impossible to get in such a short amount of time. Jaya decided to sell his house to pay the ransom.

Even with the ransom in hand, he struggled to escape.

“I had the ransom, but they wouldn’t let me go home, and that’s when they actually broke their own rule,” Jaya said.

'I had no choice': Jaya (left) poses with other two Indonesian victims of a scam company in Myanmar. (Courtesy of Jaya) (Courtesy of Jaya/.)Jaya and fellow employees then met an Indonesian trafficker who would help them to get out of the “hell dormitory”.

Jaya and others were let free, but their bosses kept their passports. When interviewed on Nov. 15, 2022, Jaya was in Bangkok, waiting for the arrival of the documents that would allow him to return home to his family.

“That was a valuable life lesson for me, and I hope other people will not go through what I did,” Jaya said.

Foreign Ministry citizen protection director Judha Nugraha said that since 2020, the ministry had received at least 703 reports of cases of human trafficking related to online scam companies. Judha added that 623 of the migrant workers who were trafficked had been brought home.

Judha said the ministry was making efforts to minimize the trafficking of Indonesians. The ministry offered protection to the victims by helping them get back home.

The ministry also provided counseling for the victims and was conducting a public awareness campaign against job scams.

It was also working with the Social Affairs Ministry to rehabilitate victims and with the National Police's Criminal Investigation Department (Bareskrim) for legal recourse and to identify traffickers outside the country. In these cases, Indonesia would need to cooperate with other countries to facilitate the legal proceedings.

Judha added that most of the undocumented migrant workers who ended up being trafficked abroad lacked knowledge of Law No. 18/2017 on the protection of migrant workers. The 2017 law defined the rights and obligations of Indonesian migrant workers in an amendment to the old legislation enacted in 2004. However, to Judha's surprise, not all of the individuals considered themselves victims of trafficking.

“There have been some individuals who refused to join the counseling. But there have been cases where the individuals are heavily depressed because of the unwanted experience,” Judha said.

The Foreign Ministry citizen protection director noted that of the 15 reports of Indonesians being trafficked in Laos, 11 saw the people trying to get back to Laos by applying to similar scam companies.

“It’s a complex case. There are the victims of human trafficking, but there are those who ended up working at a port,” Judha said.