Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFace the past: Indonesia needs an exhibit commemorating the dark side of its history

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he Czech Republic’s Museum of Communism prompts the question whether Indonesia could similarly acknowledge its history’s less-glorious moments

Among the dozens of exciting places to visit in Prague’s Old Town, the Museum of Communism looks somewhat out of place. Not only for its theme, but its modern structure, which stands in contrast with the large churches and bridges around the same area. Those old structures, built during the medieval ages, remind visitors of the Christian empire's heyday of the past.

The idea of a communist museum raises questions about whether one would want to allocate one or two hours of their stay in Prague to view exhibits of such a realistically sordid kind.

Why would a nation dedicate a museum to an ideology that caused so much pain to millions worldwide? Would you want to visit a museum commemorating and glorifying the ideology? Curiosity got the better of me, and it turned out the two hours touring the single-floor museum were well invaluable, with many takeaways for a visitor from Indonesia.

Below the large print “Museum of Communism” is a subtitle reading “Dream, Reality, Nightmare”. It becomes clear that this is a museum focused on the Czech Republic’s tragic experiment with socialism-communism from 1948-1989. One obvious takeaway for Indonesians is the museum shows what would most likely have happened to Indonesia had it taken the communist path in the 1960s.

A less obvious but more important lesson is that the Czech Republic has been able to come to terms with its past, documenting the journey of trying and failing to put communism into practice. What started as a dream, people soon learned, became a vastly different reality. Over time, the regime became more repressive, trying to impose the vision.

In Indonesia’s history of power struggle, communism was soundly defeated by the army in 1965. Still, for the next three decades following that, Indonesia was ruled by a regime just as ruthless as its communist counterpart in then-Czechoslovakia.

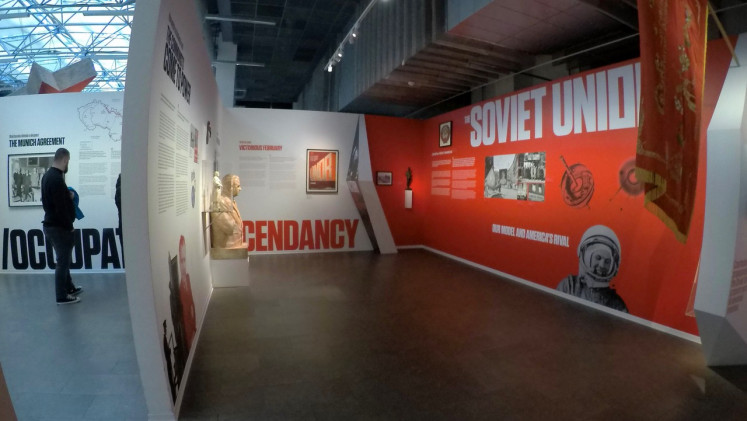

Propaganda: Part of the communist dream is the propaganda boosting the role of the Soviet Union in leading the Eastern bloc competition with the West. (JP/Endy Bayuni) (JP/Endy Bayuni)One difference is that Indonesia has yet to accept its ugly past. Attempts to uncover the truths have consistently been foiled, from the massacres in 1965-66 to the brutal suppressions of dissents and the massive corruption that bankrupted the nation in 1998.

You will not find much in the official history books and national archives, and no museum to remind us of this dark period in Indonesia’s modern history. Since it is not in our collective memory, there is the danger we fail to recognize as a new form of authoritarianism creeping in now.

As the famous saying by Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana goes, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”, Indonesia could soon follow other Asian, African and European countries that have reverted to authoritarianism after a brief period of democracy.

Entering the Museum of Communism, you are greeted by the status of the Father of Communism, Karl Marx, the German philosopher who introduced the theory of the stages of society with communism at the apex. The museum divides the stages of communism as practiced in Czechoslovakia.

Stage one (the dream) tells the story of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seizing power in 1948 with Soviet backing, and thus began the socialist experiment, glorifying the ideology and promising equality.

Stage two (the reality) is devoted to policies and practices to achieve the communist dream, including the forced collectivization of farms and a massive industrialization program. This section depicts the “socialist hero”, ordinary working men and women dedicated to the ideology.

This section also displays many products that workers made, including motorcycles, bicycles and sports equipment. A poster shows the Spartakiada, mass synchronized gymnastics held every five years at Prague’s Strahov stadium, a vast structure the size of six football fields.

This section also shows the tools used by the government to discipline workers and dissidents, such as a long-lensed camera, a handgun issued for the SNB secret police and devices to torture people.

The final leg of the communist experiment is when it becomes a nightmare. By the mid-1960s, people began to speak out, not so much against the ideology for fear of repercussions, but demanding more freedom. First Secretary Alexander Dubcek launched a series of reforms to introduce “communism with a human face”. This experiment in 1968, called the Prague Spring, was abruptly halted when Soviet tanks rolled into town, and Moscow imposed a regime that rolled back all the reforms introduced.

What followed in the next two decades, as depicted in the museum, was the build-up toward the Velvet Revolution in November 1989 when communist rule ended. There were brutal police repressions against students and dissidents. A bunch of young activists kept their hope alive. One of them was writer Vaclav Havel, who was jailed many times but became the president of Czechoslovakia after leading the revolution.

This last phase in the museum is the most relevant for Indonesia since we have failed to document the resistant movements and the dissidents, including poets and writers, who were critical of the military-backed regime of Gen. Soeharto, who ruled from 1966 to 1998. They did exist, and the military brutally suppressed them.

Many of these movements were led by students, but the New Order regime brutally suppressed them. In 1980, 50 activists, including former generals and ministers who had supported the government, wrote a “statement of concerns” criticizing Soeharto for personifying the state ideology Pancasila and using it to silence critics. The regime cracked down on the members of The Group of 50, as the dissident group was dubbed, depriving them of access to livelihood, such as having bank accounts and barring the media from reporting their activities.

Since the regime controlled the Indonesian press, we cannot expect to find much from their archives to reveal what happened during Soeharto’s New Order. Ditto with Indonesia’s 24-year brutal occupation of East Timor (now independent Timor Leste). As with the Czech story of communism, you are more likely to find credible information from the archives of foreign media reporting on Indonesia.

The Museum of Communism in Prague was built in December 2001, 12 years after the collapse of communism. Videos of interviews with scholars, dissidents and survivors played out at the museum to help visitors understand better while observing the many artifacts.

It has been nearly 25 years since the collapse of the Soeharto dictatorship, and we are not even close to uncovering the many ugly truths about the regime. A museum to remind us of the horrors of the regime, similar to the museum in Prague, would be a great idea if only to remind the nation of our ugly past. We owe it to ourselves and our children and grandchildren to know the reality of Soeharto’s New Order.