Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe best climate solution for Indonesia lies with its people

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

D

espite the government’s commitment to recognize 1.4 million hectares of new indigenous forest areas between 2025 and 2029, announced ahead of the United Nations Climate Summit (COP30) this month, the target remains far from sufficient, according to an expert.

Farah Sofa, program officer at the Ford Foundation, said that the Ancestral Domain Registration Agency (BRWA) has already mapped over 30.1 million ha of indigenous territories nationwide. Yet, as of late 2025, the government has formally recognized only 345,257 ha.

According to her, this vast recognition gap leaves extensive, carbon-rich lands vulnerable to exploitation and deforestation.

“The consequences are already evident. Since 2001, Indonesia has lost approximately 32 million ha of tree cover, releasing an estimated 23.2 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. Much of this loss can be traced to the ongoing failure to secure indigenous land tenure,” she said.

She emphasized that this issue is not merely a matter of legal reform or social justice, it is a climate imperative.

Farah added that extensive research has shown that deforestation rates are significantly lower in territories where indigenous peoples hold formal legal rights.

“Their ancestral knowledge, governance systems and traditional land management practices form a robust defense against illegal logging, mining and plantation expansion, the primary drivers of Indonesia’s emissions trajectory,” she said.

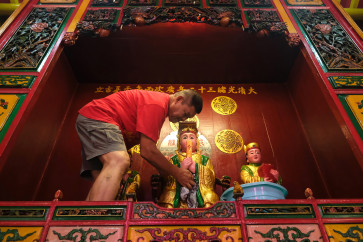

Customary deliberations held by the Manusela Indigenous Community in the northern part of Seram, Central Maluku, Maluku. (Images courtesy of Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN))She highlighted the Dayak Iban communities in Kalimantan as a vivid example. “While industrial logging and large-scale palm oil plantations have stripped much of the island’s forests, areas managed under the Dayak Iban’s hutan adat [customary forest] remain largely intact. Their centuries-old, community-based stewardship preserves biodiversity and protects carbon-rich peatlands, achievements that top-down government policies have struggled to replicate.”

According to her, Indonesia already possesses ample data and evidence of this success. “The stewardship of indigenous peoples and local communities [IPLCs] represents the country’s most effective, proven and economical defense for global forests. Granting full legal titles to community lands serves a dual purpose: it upholds inherent human rights and fortifies the nation’s most critical natural defense against the global climate crisis,” she said.

Farah noted that for decades, the communities that hold the key to Indonesia’s natural resilience have been denied legal authority over their ancestral territories. “This is not only a historical injustice but also a strategic failure that undermines national climate goals,” she said.

While the government’s recent announcement ahead of COP30 marks a positive step, she said the real challenge lies in translating these commitments into large-scale implementation.

Recognition of indigenous rights

“We urge Indonesian leaders to accelerate the recognition of indigenous rights, both domestically and internationally. With over 30.1 million ha of indigenous territories already mapped by the BRWA, incremental targets such as 1.4 million ha fall short of the urgency that the climate crisis demands.”

A Namblong woman from the Grime Nawa customary area, Lembah Grime, Papua, shows her harvest of gedi putih or swamening, a local food source consumed as a substitute for fish and rich in nutrients. (Images courtesy of Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN))She further stressed that real progress requires acceleration that matches the scale of indigenous stewardship already documented on the ground.

According to her, reform must also focus on harmonizing and clarifying legislation to eliminate bureaucratic barriers that have long delayed recognition.

“National laws should create a swift and transparent pathway for securing ancestral land titles, rather than the current multi-year struggle complicated by overlapping regulations and inconsistent administrative processes,” she noted.

Farah also emphasized the importance of institutional capacity and resources. “Ministries and implementing agencies need clear authority, adequate funding and effective coordination to translate recognition targets into measurable outcomes, actions that are implemented, monitored and enforced,” she stated.

“Only through this comprehensive approach, accelerated recognition, legal harmonization and resource-backed implementation, can Indonesia demonstrate genuine climate leadership and honor the rights of its indigenous peoples, both at home and before the international community.”

She concluded that the fate of Indonesia’s forests, the stability of the global climate and the well-being of future generations depend on decisive action today. “The guardians of these lands are ready; it is now time to provide them with the legal tools they need to protect everyone’s future,” she said.