Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsAnother day in paradise: Redeeming value of art

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

n art exhibition titled Another Day in Paradise opened this week as part of the Sydney Festival in Australia. But it is not just another exhibition for Australia or our region for that matter.

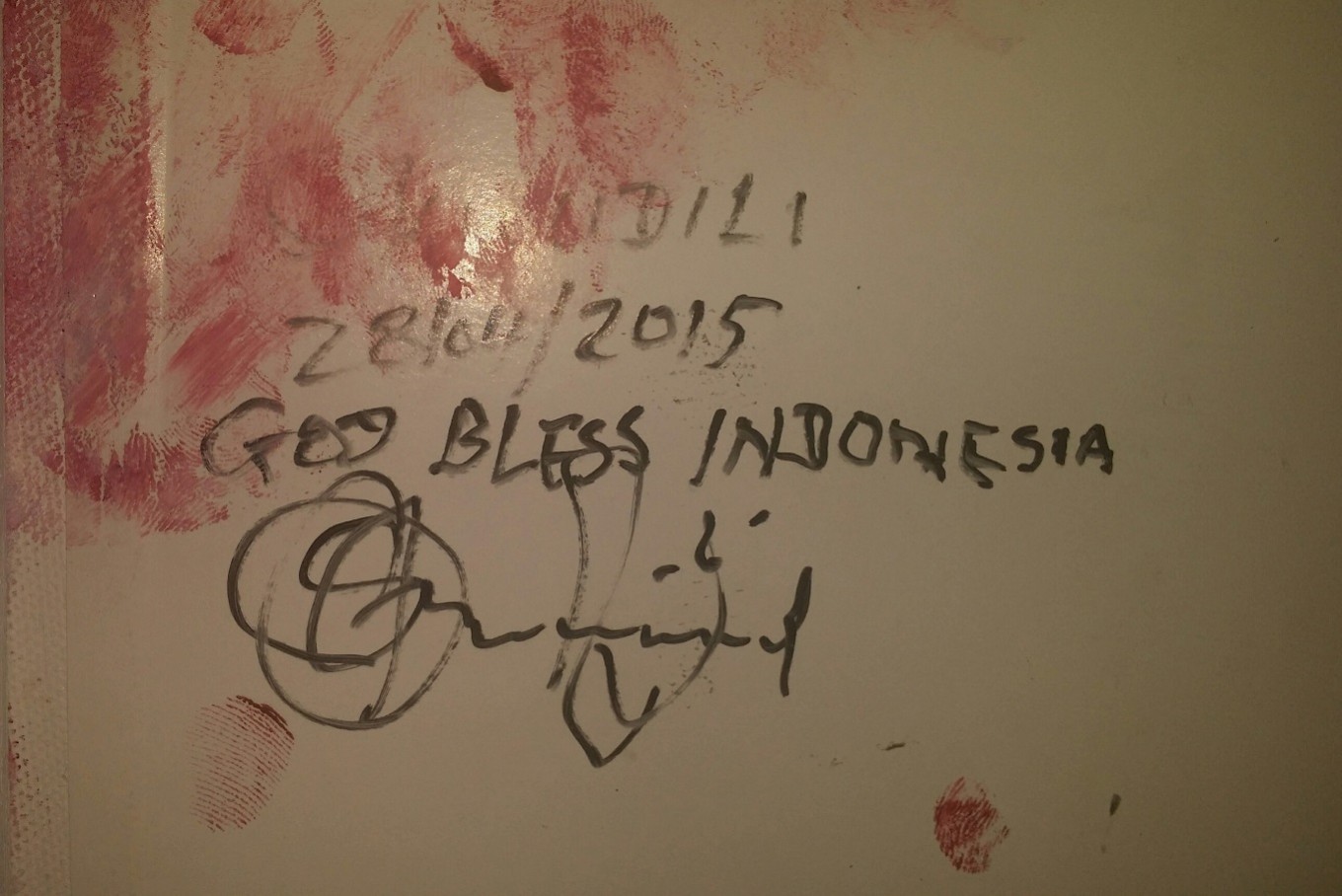

The works were all created within the boundaries of Indonesia’s own sovereign land, inspired by the featured artist’s surroundings and unenviable destiny. Myuran Sukumaran was executed along with fellow Australian Andrew Chan and six others in Indonesia on April 28, 2015. This day has been branded into the hearts and minds of their families and many Australians, as well as Indonesians. The signatures and messages of the others who were to be executed on that day were recorded on one of the last paintings to be rendered in an expressive replica of blood and spirit.

Australia has a deep cultural affection for its convict origins. Outlaws like Ned Kelly and the mythological “jolly swagman”, the thief-hero from Australia’s unofficial national anthem “Waltzing Matilda”, are imbedded in Australian history, pride and nationalism. Many statues have been raised in town squares and municipal parks across the country celebrating reformed convicts who often became civic leaders.

Important Australian art has been inspired by these law breakers, thieves and murderers yet, as a nation, Australia has struggled with the crimes and the time of its own Australian sons. By all accounts, they too were ultimately deserving of our forgiveness, attention, pride and support. After all, they only wanted to continue with prison work for the rest of their lives. No one was asking for a “get out of jail” card.

The broader arts community and its followers have done much of late to help transform and promote the reputation of the young failed drug trafficker Sukumaran into an astonishing, empathetic and courageous symbol for the antideath penalty movement. His sculpted, vibrant paintings bear the unmistakable influence of his teacher Ben Quilty, Australia’s best known and most successful award winning portrait artist and cocurator of the current exhibition.

The majority of Sukumaran’s work up to 2012 was rather flat and unremarkable as he spent his time trying to improve his technique in prison, without much professional guidance. He had been previously told to copy subjects from the covers of magazines. This would explain the lack of character and life in his early work. Later Sukumaran would joke about hiding that original work from public view, feeling that he had turned a significant corner after finally working with Quilty. He began to really discover how to mix paints under Quilty’s guidance, not long after the latter’s first visit in December 2012.

In a definitive moment on Feb. 8, 2013, Quilty was teaching a masterclass at the prison and sent through an exuberant message, exclaiming: “Myu has had a painting revelation! He sees how to paint! Really paint! Honest observation, with mixing and creating... Myu may not have been a real drug kingpin but he is definitely the King of Kerobokan!"

It would be fair to say that Sukumaran’s authentic arts practice really began at that moment.

Signature and messages of others who were to be executed on April 28, 2015.(JP/Mary Farrow)

Signature and messages of others who were to be executed on April 28, 2015.(JP/Mary Farrow)

Art became Sukumaran’s medium to express his mortality to anyone who would listen. He feverishly produced works in his last couple of years and developed his talent at an exponential rate, while enduring the ever-present threat of being killed and his clemency appeal, which would wither away on a faraway desk somewhere. He grappled with his impending finality by conjuring up colorful oozing images from pallet to canvas.

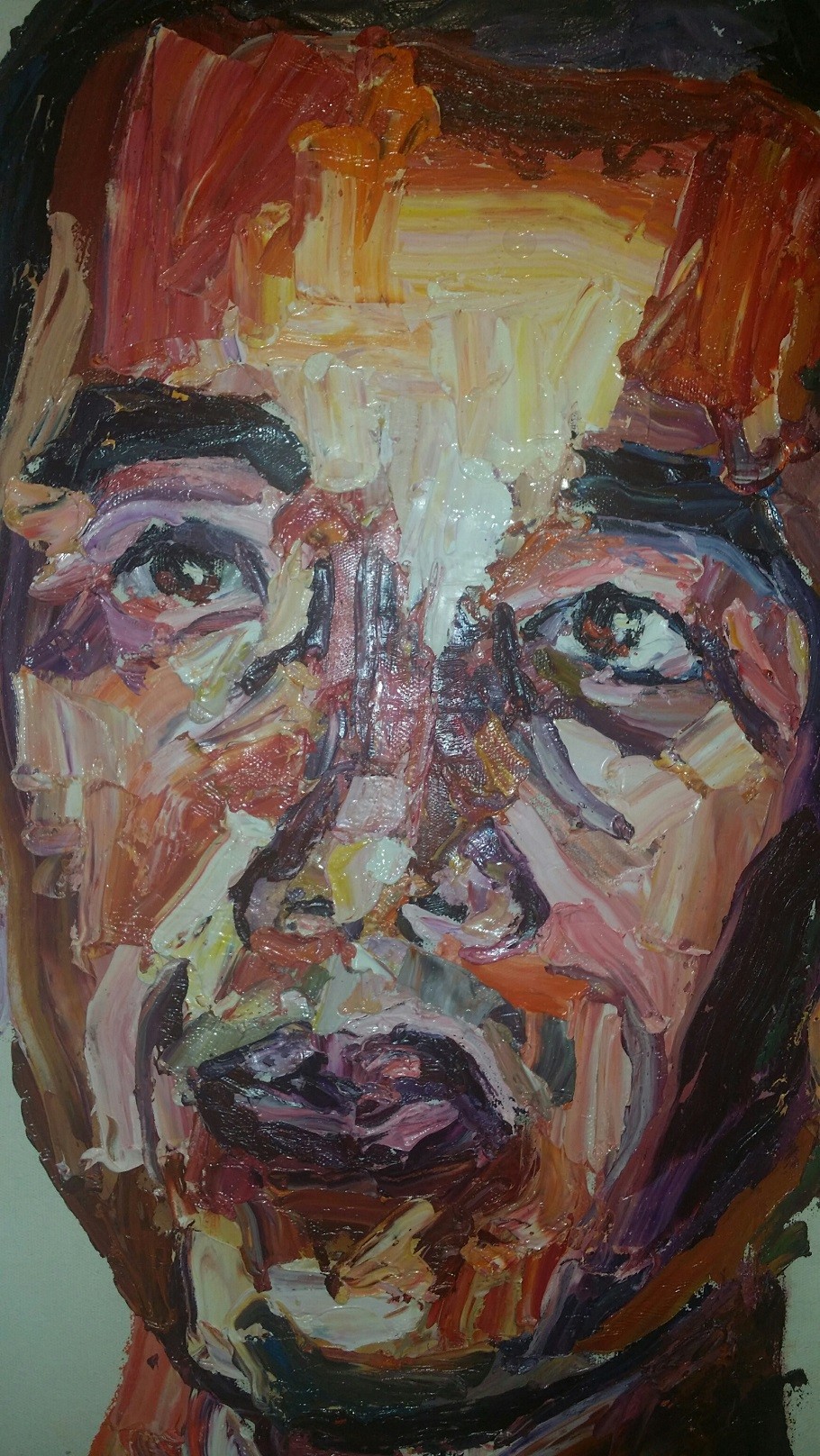

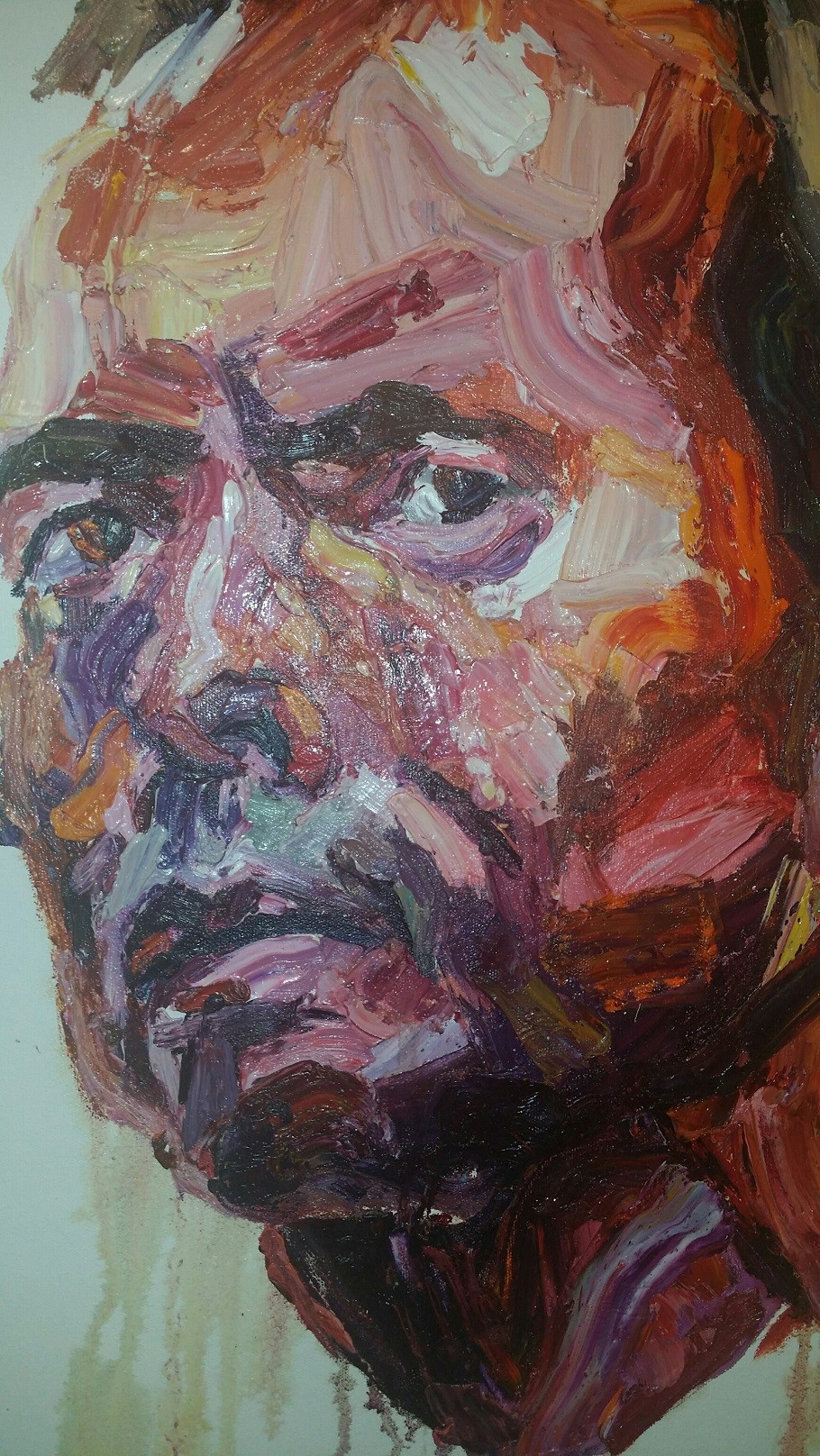

His series of political decisionmakers stared back at him from the canvas as his right to live was dangled over his head just out of reach and he was teased and tormented in a flexing of political muscle. Remarkably, Sukumaran also completed an associate degree in fine arts through Curtin University from within the walls of Kerobokan, a feat that some ordinary students can struggle to complete without a firing squad waiting for them.

On March 30, 2013, Sukumaran’s prison art studio was visited by then law and human rights minister Amir Syamsuddin, who readily praised the education programs and workshops provided by the young Australians in Kerobokan. He commended the workshops, including the art studio, the silversmithing, silk screening workshops and the computer room.

"I will suggest to the provincial chief to file patents for their works," Amir said. "There's a lot of potential to work with overseas partners to market the products made by the prisoners."

Indeed there was.

The accomplishments were barely the tip of the iceberg for Sukumaran, who had by then spent a third of his young life in prison. He learned in prison how to paint to a professional standard, achieved an academic qualification and completely turned his life around at no cost to the Indonesian government, with support from the wardens, NGOs, academia, family and friends.

He had already paid 10 years of his life for a failed crime he had committed a decade earlier and spent the bulk of that time helping others to become educated, productive, caring members of the inmate community. Sukumaran proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that reform is not only possible and measurable, but that others would enthusiastically assist in the process, to the benefit of the prison environment and Indonesia’s reputation. The same result would not have occurred in Australia.

A portrait of Indonesian President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo.(JP/Mary Farrow)

A portrait of Indonesian President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo.(JP/Mary Farrow)

While some might declare that Sukumaran’s style was nothing more than a Quilty reinvention, there is nothing unusual about students following their master’s technique as they develop their own style. Sukumaran emerged as a serious talent in only two to three years, which is quite extraordinary, but the pressure was on and he had tremendous focus. This is clear evidence that when people have the right instruction, environment and motivation, they can change their opportunities and outcomes. This is an important message for justice ministers, judges, politicians and lawmakers.

In that same year, Sukumaran had remarked that Ben’s workshops had equipped him and other inmate artists with skills that “saved years of everyone’s lives” in their ongoing arts practice. This seemed to be a remarkable and genuine statement by one whose own life was destined to be cut short. But it is a natural human trait to have hope. “What else is there if we don’t have hope” former US first lady Michelle Obama said upon her recent departure from the White House.

Quilty’s masterclasses contributed to better paintings and improved sales of prison artwork, which helped cover the costs of the program. It was a sustainable practice in many ways and cost the Indonesian government nothing. The inspiration of the activity attracted many benevolent outsiders who beat a path to the door of the unlikely art school. Some past inmates even returned to the prison to attend classes. The prison also won the National Prize for best prison art in 2013 due to Sukumaran’s studio and the silversmith workshop driven by another young Australian, SiYi Chen, which continues to churn out skilled artisans who find employment in the local jewelry industry.

It is incredibly sad that President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo never paid a visit to Kerobokan Prison as others did or reviewed any of the projects that were delivering education to Indonesian inmates. The work that went on in Kerobokan Prison in an Indonesian-Australian de facto partnership for years should have certainly raised the interests of criminology, education and employment ministers at least.

A portrait of former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott.(JP/Mary Farrow)

A portrait of former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott.(JP/Mary Farrow)

A representative of the National Narcotics Agency’s (BNN) international division was also privately invited to visit the prison in 2013 to view the efforts of the young Australians. He was so impressed with what he saw that he reported on Radio Republik Indonesia that he “had seen people who were lost and now trained and empowered to live as a better person”. It would be fair to say that everyone involved could see the benefits and potential of what was happening inside Kerobokan.

Another Day in Paradise is a challenging and provocative art exhibition and will no doubt disturb many, and so it should. Sukumaran conjured up images that leave people feeling a sense of lost opportunity, pride, anger, failure and trauma. It also imparts an inspiring story of resilience, especially for those who were involved, of learning, friendships, joy, potential, humor and chance.

The executions have forever bound Indonesia with Australia in an inextricable embrace in this perpetual agitated tango between two neighbors. Sukumaran and Chan have set the agenda with their lives in a mock-Shakespearean tragedy and it is up to ordinary people to bring this calamity to a more respectful progressive finale in a salute to human rights in their honor. Eventually, politicians and lawmakers will follow.

Reeducating inmates with a skill contributes to a decline in repeat offending, a fact that has been much researched globally. It is ripe for following up with an Indonesian scholarly study of the evidence that the death penalty does not lead to a reduction in drug offences. Jobs, skills, education, self-respect and a sense of community are the successful weapons in the drug war.

Australian universities that are keen to hand out free scholarships to Indonesians should designate them for master’s degrees and PhDs in restorative justice and research. By exercising the death penalty, governments say there is no future or hope for people entangled in crime, no ability to change, learn or help others. It is a death sentence for humanity and a failure of hope.

It is time for some new, authentic and measurable evidence in courtrooms and presidential palaces. Eventually US decisionmakers will follow.

Myuran Sukumaran: Another Day in Paradise

Jan. 13 to March 26

World Premiere curated by Ben Quilty and Michael Dagostino

Cambelltown Arts Centre

***

Mary Farrow, an American living in Australia, is the director of the Centre of Resilience and on the board of the ASEAN Literary Festival, occurring on Aug. 3-6, 2017, in Jakarta.

---------------

Interested to write for thejakartapost.com? We are looking for information and opinions from experts in a variety of fields or others with appropriate writing skills. The content must be original on the following topics: lifestyle ( beauty, fashion, food ), entertainment, science & technology, health, parenting, social media, travel, and sports.Send your piece to community@jakpost.com. For more information click here.