Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe Loner: Yudhoyono's squandered decade

A long-term observer of Southeast Asian affairs casts a critical eye at the 10 years in office of Indonesia’s sixth president.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

f one were to call Central Casting looking for a veteran Western news reporter who has spent decades covering the ups and downs of politics and society in Asia, one would no doubt seek a great bear of a man.

Ideally, he would be hunched over his Remington typewriter furiously hammering out his copy as he swiped away a mane of grey hair, while thinking about his next meeting in some backstreet shebeen or at the State Palace in pursuit of another lead.

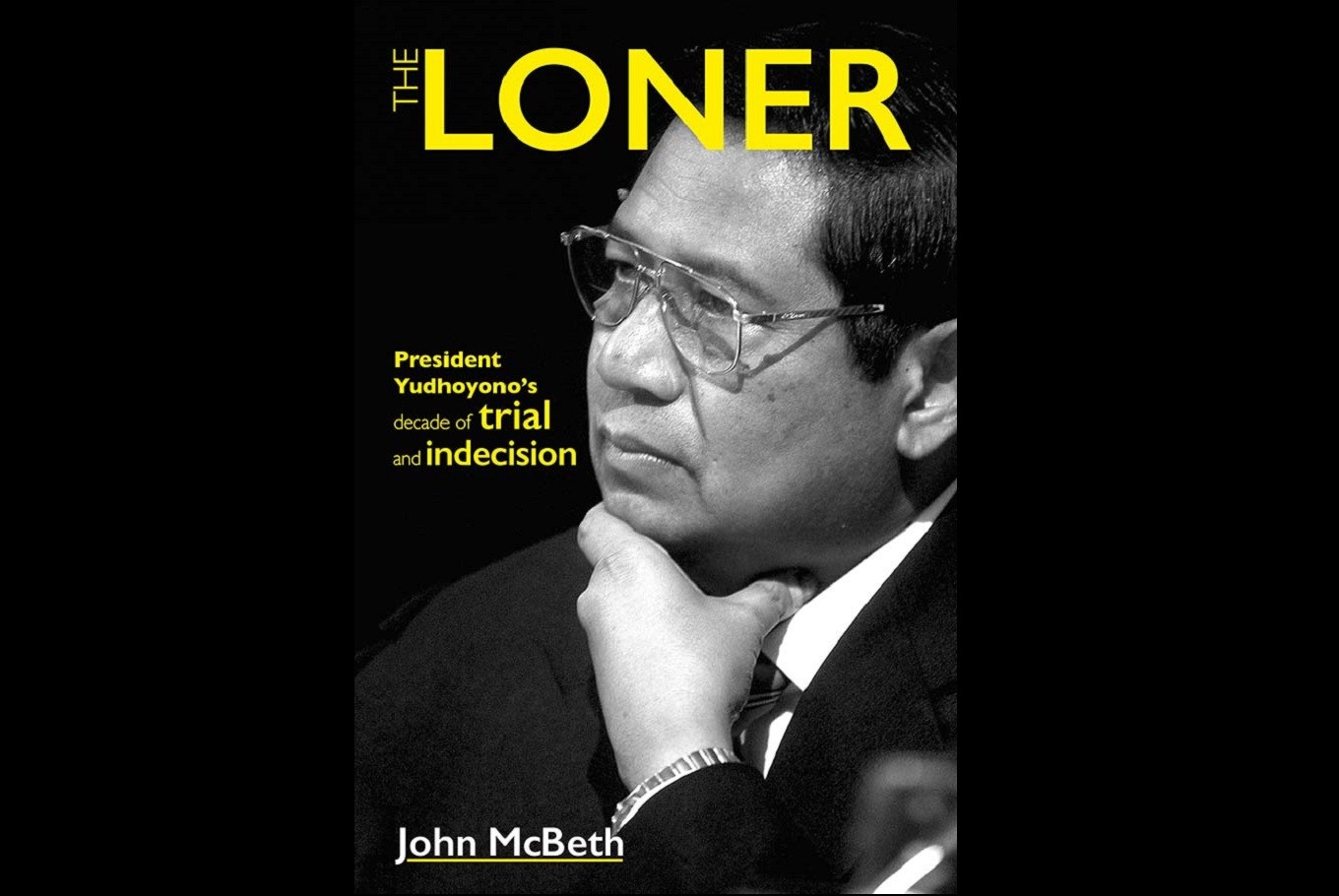

John McBeth certainly seems to fulfill this caricature admirably. Presenting his book The Loner, President Yudhoyono’s decade of trial and indecision at a recent Jakarta Foreign Correspondent’s Club event in the Writers Bar at Raffles Hotel, he described himself as an oldfashioned journo — a typewriter, paper and ink man for his 55-year journalism career.

He started his career at his hometown paper in New Zealand, where he learned the trade, and then over the best part of half a century in Southeast Asia.

McBeth knows of what he speaks when it comes to the politics and personalities of Indonesia; over time he has amassed a hoard of sources, and has tapped this to its fullest extent in his critical examination of the presidency of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

It was McBeth’s original intention to title his book “The Lost Decade” but friends and colleagues advised him against it for being too harsh. Anyone who lived through the 10 years of the Yudhoyono presidency, a decade of remarkable growth, peace and prosperity in Indonesia, would probably concur with the decision.

McBeth accepted the advice and went instead with the title The Loner, for that is the characteristic of the notoriously prickly sixth president of Indonesia that struck McBeth the most.

Yudhoyono is painted as a man with few personal friends and allies. His closest and most listened-to advisers are his formidable wife Kristiani and other members of his immediate family circle, who as a result sought to build a coalition as wide as possible, on consensus rather than loyalty to him as leader.

The absence of basic personal loyalty is a failing about which McBeth is most scathing — not a lack of it from subordinates, however, but Yudhoyono’s own disloyalty when it came to hanging out to dry his finance minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati and vice president Boediono during the Bank Century fiasco.

However, given that the 10 years of Yudhoyono’s two terms might in later years be seen almost as a “golden decade” in Indonesian history (as described by the World Economic Forum), what is it about Yudhoyono that McBeth finds most disappointing?

Fundamentally, it is about missed opportunities. A fresh new leader, widely regarded as competent and free from corruption, Yudhoyono swept into office on a tide of great goodwill; he could have done anything he chose but ultimately left office having achieved little of any real or lasting substance, with the obvious exception of peace in Aceh.

Yudhoyono, despite being a four-star general, was a remarkably timid man when it came to implementing tough policy decisions, says McBeth.

Particularly when it came to the absurdly ballooning fuel subsidies, which could easily have been tackled with determination early in his presidency, thus freeing up valuable resources, both financial and political, for more complex issues later in his term.

McBeth describes how Yudhoyono was obsessed with the fear that rising fuel prices brought down Soeharto, despite the perfect storm of other crises that led to the end of the New Order Era. Conversely, Yudhoyono convinced himself that cutting fuel prices led to his reelection in 2009, an election in which McBeth believes he was in fact already a shooin.

Ultimately, it was the problems that began to gather steam on his watch that will be Yudhoyono’s legacy, the baleful effects of which are becoming apparent today.

Among these is his failure to support the work of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK).

When the KPK successfully prosecuted the father-in-law of Yudhoyono’s son, Agus, it appeared that Yudhoyono’s anticorruption credentials had been vindicated. However, McBeth writes that within the First Family, the reaction was profound and pressure on the KPK began to increase. The ramifications of this period, and the later jailing of then KPK chief Antasari Azhar, have begun to unravel in recent weeks.

Ultimately, it is the instigation of economic nationalism, particularly with relation to mining giant Freeport, the ramifications of which are also front-page news today, that McBeth sees as the worst blot on Yudhoyono’s copy book.

Overall, McBeth weighs Yudhoyono’s record in a balanced manner; his presidency was by no means a litany of failure — far from it — but the fact remains that while his decade in office was not “lost,” much of it was nonetheless squandered.