Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe burning memory of colonialism

The Oude Kerk, Amsterdam’s oldest building, was specifically chosen by Europalia due to its strong ties with colonial history, Oude Kerk director and curator Jacqueline Grandjean explains.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

U

nderneath Iswanto Hartono’s solemnly beautiful exhibition in Amsterdam lies a powerful message of the colonial times for both Indonesia and the Netherlands.

Entering the grand, hushed hall of the 14th-century Oude Kerk (old church), visitors might easily overlook the statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen standing in the left corner beyond a wrought-iron door.

The head of the life-sized statue glows in a soft, luminous red, and only up close it becomes clear that it is set alight: the statue is made out of wax, and will burn throughout the eight-week solo exhibition by artist Iswanto Hartono, ending on Nov. 15.

“I chose Coen because he is such an important, yet controversial, historical figure in colonial history,” says Iswanto.

The exposition is part of Europalia, a biannual arts and cultural exhibition based in Brussels. Each time, one country is highlighted throughout the nine-month event, and Indonesia is its focus this time. Until now, Iswanto is the only artist exhibiting work for Europalia outside of Belgium

The Oude Kerk, Amsterdam’s oldest building, was specifically chosen by Europalia due to its strong ties with colonial history, Oude Kerk director and curator Jacqueline Grandjean explains.

The gothic building is now a museum and arts exhibition space, and still functions as a church on Sundays. Like many old churches, it is also the burial site of prominent citizens, including Jacob van Heemskerck, the Dutch captain whose ships first reached the spice islands of Banda in 1599.

The Dutch grip on Banda, with its much-sought-after nutmeg, was a milestone in the formation of the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC), a trading company which set the groundwork for Dutch colonial rule in the Indonesian archipelago.

“The church’s chapel was built with VOC money, and many of the ships which sailed to the East Indies were blessed right here,” Grandjean points out.

Grandjean set out to find an Indonesian artist for the exhibition, and Jakarta-based Iswanto was a logical choice.

“History is often part of his art. He has such a thoughtful, non-judgemental look on it,” says Grandjean, adding that his background as an architect was an advantage. “It is not easy to set up art in an old, big church like the Oude Kerk. One needs to have a good understanding of space in order to make it work.”

Monuments ( 2017 ) by Iswanto Hartono (Oude Kerk/Maarten Nauw)While Iswanto and Grandjean toyed with different approaches, such as a giant curtain made of nutmeg hanging in the main hall, it resulted in four different displays that beg contemplation. In addition to Coen’s statue, there are six wax miniatures of colonial buildings such as the lighthouse in Lampung, Fort Belgica in Banda and the Amsterdam Gate that used to stand in the old town Kota area of Jakarta. In reality, some of the buildings are still standing, while others have disappeared.

“Candles have always been used in spiritual worship, which fits in this space. It transmits light, and yet it will disappear,” Iswanto said about using wax as a medium.

“The monuments depicted were built for significant reasons, and some were later also torn down for other reasons. However, does it mean that they are forgotten once they are no longer physically there? Is that how we associate ourselves with history? In order to forget, we must remember first.”

The statue of Coen, recognized as the founder of Batavia (now Jakarta), was perched on what is now Jakarta’s Lapangan Banteng for seven decades before being torn down in 1943, during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia.

In his own country, Coen’s statue in the middle of his hometown of Hoorn has sparked ongoing controversy between those who see him as a national hero and others who see him as “the butcher of Banda.” Under his command, the Dutch killed thousands of the Banda people accused of defying the Dutch monopoly on nutmeg trade.

Banda is featured in a separate room, where a glass case contains iPads with a short film combining images and animation that tell the history of Banda.

As one enters the room, faint “local” sounds — prayers from a mosque, people speaking the local dialect — can be heard in the background. “I recorded that background track in Banda,” Iswanto says.

Trophy ( 2017 ) by Iswanto Hartono (Oude Kerk/Maarten Nauw)The most “Dutch” display is Iswanto’s silhouette interpretation of a carriage still used by the Dutch royal family for important occasions. On the side of the carriage, a gift from the city of Amsterdam to Queen Wilhelmina in 1898, is the painting Homage from the Colonies, showing the Dutch queen on a throne, surrounded by bowing subjects from its colonies, including Indonesians.

“This carriage, I believe, belongs in a museum, and should no longer be used,” Iswanto says. The continued use of the carriage has indeed been a subject of Dutch public debate in recent years.

Iswanto, born in 1972 in Purwerejo, Central Java, intertwined his family history onto a display of a table filled with heads of hunted animals from all corners of the world where the Dutch were present, including Indonesia, Formosa and parts of Africa.

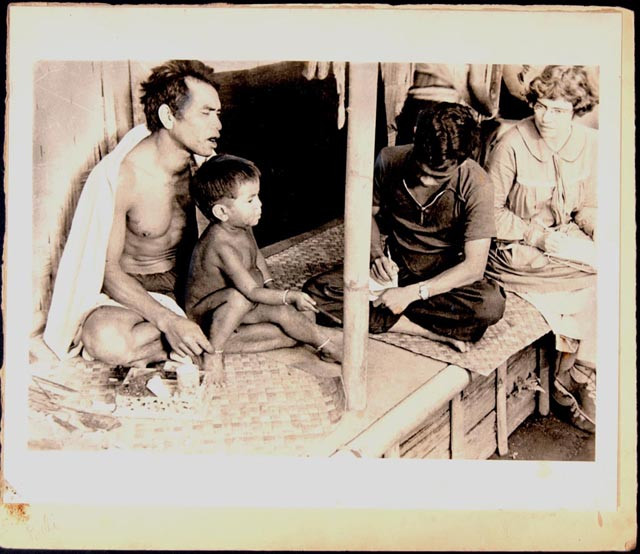

Hunting, Iswanto says, is originally for gathering food, but it can also be seen as an act of conquering, with the heads as trophies. “But hunting is also very personal for me, as my grandfather and my father used to hunt,” Iswanto explained. On the wall are old family photos of his grandfather’s hunting excursions in the early 20th century.

The exhibition was featured in Volkskrant and NRC, the two main dailies of the Netherlands, which is exceptional for a solo Indonesian artist. Volkskrantwrote that the exhibition was “a poetic comment of Iswanto Hartono on the disappearing realization that the Netherlands and Indonesia have a shared past.”

Historian Wim Manuhutu praised Iswanto’s work for sparking the question of “the value of monuments and the stories behind them. And that one can, and should, look for the stories behind the standard explanations of those monuments.”

“It was so interesting to get the perspective of an Indonesian artist on our shared colonial history. He’s done it in such a way that viewers can form their own opinion instead of teaching us a lesson,” said Floortje Doornik, an Amsterdam resident who came to the exhibition. “The fact that it’s situated here, in an old church full of history, also lends to contemplation.”

Grandjean points out, however, there were also critical voices. “Some people were dismayed that such an exhibition was done in the Oude Kerk, which they saw as a symbol of Dutch glory.”

In his opinion piece in the NRC daily, Iswanto wrote: “Street names are changed, monuments are taken down and buildings are destroyed. But the VOC’s true legacy — a corrupt system — was not destroyed by purging the monuments. As a matter of fact, the Soeharto era was synonymous [with] corruption.”

__________________________

For further details, please log on to oudekerk.nl/en/programma/iswanto-hartono/