Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThere is hope for peaceful diversity: The Chinese Indonesian Literature Museum

Established by an Acehnese, the Chinese Indonesian Literature Museum brings hope to Indonesia’s tenet of Unity in Diversity.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he Jakarta Post arrived at the Chinese Indonesian Literature Museum on Tuesday mid-morning. Its white façade was graced with a small red signage and the museum is easily identified among a rather quiet shop house complex in South Tangerang, Banten.

Azmi Abubakar, the founder of the museum, later arrived to unlock the building and welcome The Post himself. Although unheard of by most people other than researchers and those with concerns over Chinese Indonesians, the museum can be easily found by Google map. The destination is even listed in the ride-hailing app Go-Jek.

“That’s because we often order food using Go-Food,” said Azmi with a smile.

We entered the museum through a double door decorated with old signages, pin-ups and vintage posters related to the Tionghoa (Chinese) culture. Azmi immediately showed us around.

Museum Pustaka Peranakan Tionghoa (Chinese Indonesian Literature Museum) is located in South Tangerang, Banten. (JP/I Gede Dharma JS)“The May 1998 riot was so unimaginable to me, as there had been no significant signs of hatred toward the Chinese Indonesians beforehand,” Azmi said as he explained why he was moved to establish the museum.

He recalls how the 1998 student demonstrations were initially conducted in harmony among activists from different backgrounds, including the Chinese Indonesians. But in May that same year, property and businesses owned by Chinese Indonesians were targeted by mobs, and more than 100 women were sexually assaulted. Azmi said that it was a terrible blow for him.

“What happened in 1998 was a very bad memory for Indonesians, but it was so much worse for the Chinese-Indonesians,” he said.

Wondering why there had to be ethnic violence toward Chinese descendants, Azmi started to consult various books. He had always loved books and reading, and since that 1998 riots, his interest in books about the minority group only grew.

He started collecting books, magazines, newspapers and other printed materials related to the Chinese Indonesians in the early 2000s and kept them to himself. Meanwhile, he opened a secondhand book store in 2001 to sell his other collection of books.

From the books he read, Azmi discovered that many Chinese figures had contributed to Indonesia’s history, and its struggle for independence in particular.

Azmi concluded that what happened in 1998 was similar to what the Dutch colonizers did across the archipelago for hundreds of years: divide et impera (divide and conquer), a strategy used to separate the Chinese descendants from native Indonesians. The separation was intended to break a large concentration of power into pieces with less power.

The archipelago is more vulnerable when the Chinese descendants and Indonesians are divided, and some parties who see the benefit of this vulnerability will continue to keep the two groups separated.

“There seems to be a systematic effort to halt the spread of positive information about the Chinese Indonesians,” said Azmi, who felt he finally had a large enough collection of books and other items to open the Chinese Indonesian Literature Museum in 2011.

The museum aims to deliver information to create understanding between the Chinese descendants and so-called native Indonesians. Azmi is sure that a mutual understanding would prevent Indonesians of different backgrounds from attacking each other.

Read also: Pasar Lama Tangerang: Witness to history

In between sharing his stories with The Post, Azmi showed some of his most prized collections. There were series of comic books in the Malay-Indonesian language written by Chinese-Indonesian authors, an album filled with photos of Chinese Indonesian body builders, and a book about a journey to Bali written by Soe Lie Piet, a journalist and author who is the father of Soe Hok Gie, a renowned Chinese-Indonesian activist.

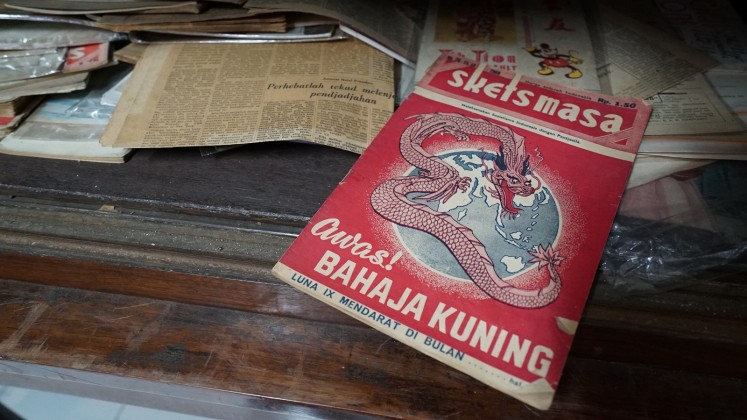

A collection of Museum Pustaka Peranakan Tionghoa (Chinese Indonesian Literature Museum) in South Tangerang, Banten. (JP/I Gede Dharma JS)There are tens of thousands more items in the 100-square-meter museum, and if a visitor is not into reading, Azmi will be more than happy to explain some of his collections. There are no catalogues yet, but visitors can simply tell him what he or she is looking for. Azmi always knows which item to show visitors.

The Post was fortunate to be Azmi’s only appointment that day, and he was not expecting any walk-ins. The museum usually caters to appointments every day. On his days off, Azmi can be found tending to his small property business.

One of Azmi’s missions is to visit local youth communities and share with them his knowledge about Chinese Indonesians.

“That is the only way to make them understand about the minority group, as their access to information is limited,” Azmi said.

It is important for the information to be delivered by a non-Chinese descendant, otherwise the response would be much different, according to Azmi, who hails from Aceh.

The civil engineering graduate turned cultural activist then told The Post about his greatest joy from running the museum.

“I am happiest when people find their roots and identity in this museum. They may discover their family history and ancestors here and leave this museum with priceless knowledge.”

On the other hand, Azmi and the museum are racing against time. As the sound of hatred is so often heard lately, the information stored within the museum needs to be spread more quickly and efficiently.