Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsShort Story: The Warrior's Sword

Donning the sarong-made ninja suit, the warrior would work on his homework and recite daily prayers.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen I returned home after having purchased a water tube, I found Ka seated at the dinner table with his arms folded across his chest. His mother meticulously cut across the slab of grilled meat on the plate with a steak knife, before devouring it slowly. Ka acted as though he was indifferent toward everything and everyone around him; yet when I moved closer to the table, he grew listless.

I snatched a grape off the table. “Not hungry, Ka?”

“I’m boycotting you,” he said, glancing sharply at me. Then at his mother. “You too, Mom.”

The words nearly got me rolling on the floor. But I decided to respect the psychology of his youth and held my tongue. My mind wandered far, though. What was going on with my son and how did he get to talk that way to me and my wife?

I grabbed a plate and quickly filled it with rice and grilled meat.

“He wanted a sword,” my wife said, waving the steak knife in her hand casually at nothing in particular, slicing the air around her. “Like this one, but bigger.”

“Not like that,” Ka retorted.

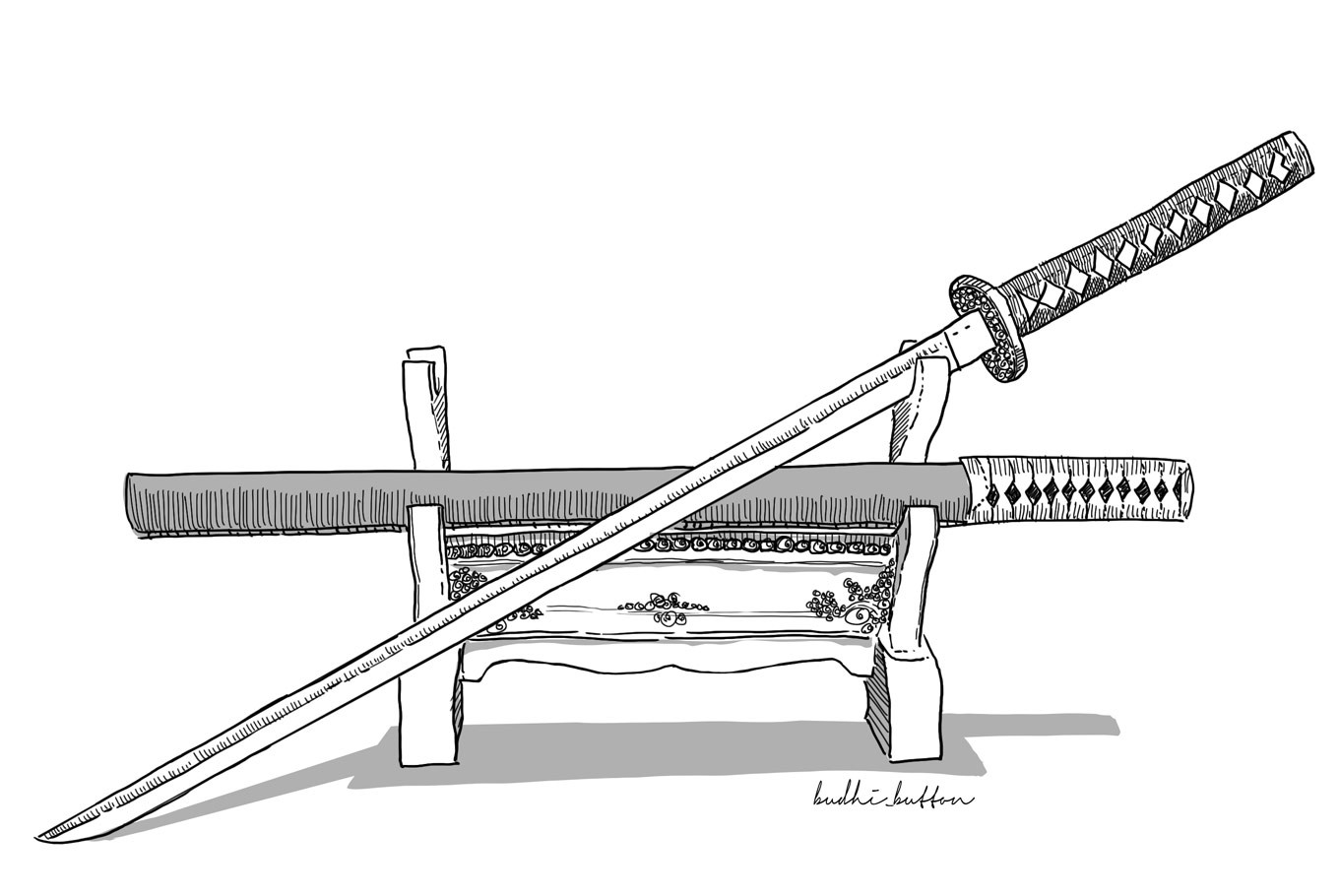

“I want a sword like the one used by Samurai warriors. A real katana, Dad — not a toy. I will continue boycotting you and Mom until the day you get me that sword. I will also hold my breath, like this.”

I asked him whether he had seen such a weapon in real life. And also where he might find a store that sold this specific type of sword.

Ka was quick to explain: he has seen the sword this morning, out on the edge of the football field. He was enjoying his Sunday playing with his kite when four ninjas suddenly appeared out of the neighborhood complex. They appeared rather charming and gallant carrying their beautiful swords. They covered their faces to hide their identities (also, because they are ninjas) and they also brought a flag. They were fighting for the truth so they could save the poor and helpless. Their whole purpose was to redistribute wealth from the rich (by stealing it) and giving it away to the poor and hungry.

My wife rose from her seat and went for a glass of water. “Those people were parading around town, campaigning. They weren’t saving the poor. You watch too many cartoon shows.”

“Ssshh,” I tried to send a signal to my wife.

“No! Mom, listen,” Ka stood up. He panicked. “I know what political campaigns look like — motorbike riders revving their engines loudly, carrying colorful flags: red, yellow, blue, white, green. Meanwhile, they’ll scream into the megaphone. They rule the streets, and they don’t pay attention to traffic signs. The police often ride alongside them. Right, Dad? Remember when we had to go to the pharmacy to buy Grandma’s medicine? You asked me to close my ears, right? That was when those people rode past us. That was them, right?”

I nodded in agreement. Then I asked him to sit down. “Let’s talk like men,” I said. “Like strong Samurai warriors.”

Ka listened intently. In his eyes I saw a burning fire filled with great imagination; and it tickled me that once upon a time I used to feel exactly the same way about the world.

At his age, I dreamed of being a superhero — the kind I used to watch on TV every Sunday.

I imagined how I would save the entire school from the threat of a giant exam report and how everyone would thank me for doing so. My mind would also concoct a scene wherein I snatched the most beautiful girl in school away from the fearful grasp of the monster, which spewed red ink and which intimidated us with heavy school subjects. Later, I would return the girl back to school, now in complete ruins thanks to the monster, smoke billowing from the ground. And as the girl was about to remove my mask.

“Can I get one, Dad?”

“What if you can’t?”

“I would boycott you,” he said with determination. “I would disown you as my father; and then I would leave this house to roam around the valleys, mountains and across the ocean to find myself several grandmasters who will teach me great things.”

“Then, go,” said my wife, teasing our son. “I’m going to the mall. I will get myself an ice cream, and if you’re not around to enjoy it with me, then all the more for me — which would be great. Because who wants to roam around a creepy forest with all the mosquitoes and snakes?”

Ka’s warrior-like pride was visibly bruised by this remark.

Seeing an opportunity, I chimed in while slowly slicing the grilled meat on my plate: “Your mother once wished she had been a princess.”

“A stern princess!” Ka was quick to interject.

I laughed; and Ka let slip a joyous giggle. My wife pouted at the both of us. We made a commitment to find a katana the next day.

“To warriors,” I said, raising my tea cup high in the air.

“To warriors,” said Ka, picking up his own tea cup and giving me a toast. He drank his tea, grabbed a plate and began to eat his dinner.

From that moment on, I began to address him as a warrior. I told him that warriors are smart and knowledgeable, which means he has to finish his homework on time. He asked for a ninja suit, and I made one for him using my old sarong. I did that once when I used to pray at dark mosques in the village. Donning the sarong-made ninja suit, the warrior would work on his homework and recite daily prayers. Warriors also sleep early, I told my son, because to save a broken world and the poor from greedy villains a warrior must be of good health. No self-respecting warriors would ever brand themselves as sleepyheads.

Because what if they had to save the world from an intense war and they showed up feeling sleepy? Wouldn’t that make it easier for the enemy to kill them?

“I don’t think warriors sleep in beds, Dad; instead, they sleep on top of a pile of hay. They don’t need pillows, either. They sleep on blocks of wood. Or they sleep on top of tree branches in the dark forest, with the moon as the only source of light,” said Ka before going to sleep.

Well, now. What was I to do? Find a pile of hay in the middle of the city? Forget the hay, we don’t even have rice fields anymore.

Fine. I would have to come up with something, fast.

“Older warriors do that,” I said. “When they were young, though, they slept at home, in bed, and they used a pillow.”

“Even a bolster?”

“Of course.”

I asked Ka to go to sleep right away, because I had to install a fish tank. Two days ago, I bought several freshwater fish, each of which I named after my childhood friends. I told Ka that warriors pray every night before they close their eyes, because the only strength that matters is one that belongs to the Almighty.

“Can a warrior pray for a katana sword?” asked Ka.

“Sure,” I said.

“And a horse?” asked Ka.

I wracked my brain for a minute. “Horses are only available for older warriors.”

“Aren’t there small horses for young warriors, Dad?”

“Let’s see whether we can find them at the animal farm,” I said.

“Animal farm?” Ka raised his eyebrows. “I thought warriors only ride horses they find in the forest.”

“That was a long time ago,” I said. “Forests no longer exist. They’ve been replaced by cities, residential complexes, hotels, airports and markets. Now go to sleep. This broken world awaits a warrior who wakes up in the morning feeling fresh and strong.”

I bowed before him, as most subjects would when saluting respectable warriors in the movies. Ka smiled and closed his eyes.

Then, just as I turned off his bedroom light, Ka opened his mouth again. “One other thing, Dad,” he said. “Warriors own roosters to wake them up every morning.”

Thankfully, the room was dark. Otherwise, he would have seen my mouth agape. Where would one keep a rooster in the city? Most roosters in the city are served on a plate, fried to perfection.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I’ve got this.” I set up an alarm on my cellular phone and changed the setting to make it sound like a rooster’s crow. I told him not to ask me whether warriors had cellular phones, because that would be an extra headache for me.

“I think they do, Dad,” said Ka.

“What are they going to do with cellular phones?” I asked. Someone told me once that patience has limits, not unlike cellular phone credits.

“Update their status,” said Ka. “My friends do it all the time.”

I narrowed my eyes in the dark: “Warriors have swords, they don’t need cellular phones. And they don’t want people to know them, which are why so many of them wear masks.”

Then I remembered how I used to imagine standing next to the girl of my dreams in front of a ruined school building with smoke billowing to the high heavens. “Unless,” I said. “You wish to be a warrior on social media whose greatness only exists in other people’s imagination.”

I hoped Ka understood such complex sentences and brand new words of wisdom.

The next day, after returning from school, Ka sat in front of the fish tank and watched a school of fish I had named after my childhood friends swim in the clear water. He was waiting for me.

We rode the bus to the shop. Ka asked me whether warriors ever used public transportation; shouldn’t they walk or ride on a flying eagle? I told him walking in the city is almost impossible nowadays, because most sidewalks are used as parking spaces or places where street vendors sell their goods. Moreover, eagles are rare creatures. I asked Ka to give up his seat for women who were standing in the bus; explaining how it would show the good character of a warrior. He did as told. I wondered what was on his mind. Did he really think of himself as a ninja, a Samurai warrior, or a robot, or something else entirely?

Earlier, I had made a call to a friend who owned a shop on the second floor of the market. He sells knives and cleavers; and I asked him whether he knew a place where I might find a katana. Upon arriving at the shop, I immediately greeted my friend.

“Master,” I said, acting as formal as possible. “A warrior has come to seek his sword.”

Ka was shy at the mention of the word “warrior”, knowing it was addressed to him.

The Master looked at my son. He rubbed the stubble on his chin, gesturing as though he was rubbing an invisible beard. “Swords usually find their warriors,” he said. “Not the other way around.”

Darn it, I thought. How did he come up with that? Was he also a fan of martial arts comic books?

“I, I meant my dad — will purchase it,” said Ka.

“Warriors can only redeem their mighty swords with sacrifice, not money.”

Well, well. My friend appeared to be just as crazy as my son. But, go ahead, buddy, I thought. Keep it going.

“Go home,” said the Master in a dramatic tone. “Perform one thousand and one acts of goodness for others and for me.” He reached for a sword which seemed to have appeared out of nowhere. “And once you have accomplished your task, you may claim this sacred sword. You know what it’s called? It’s the legendary Naga Puspa — stronger and swifter than the cheap katana you saw. This sword belongs to you. Only for you. Because, you know, this sword has been seeking a warrior worthy of its great power. And I hope you will prove yourself worthy of it!”

Ka, my firstborn, opened his mouth in awe. He was shaking.

We rode the bus back to our house. During the commute, Ka was mostly silent. I didn’t say anything, either. I didn’t want to disturb his thoughts, or the things he thought he was going to have to do to be worthy of the sword.

***

Eko Triono is an Indonesian essayist and short story writer. His collection What’s the Most Well-Suited Religion for Trees? (Diva Press, 2016) was shortlisted for the Khatulistiwa Literary Award.

------------------------------

We are looking for contemporary fiction between 1,500 and 2,000 words by established and new authors. Stories must be original and previously unpublished in English.

The email for submitting stories is: shortstory@thejakartapost.com

We are no longer accepting short story submissions for both online and print editions. New submissions to shortstory@thejakartapost.com will not be published.