Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

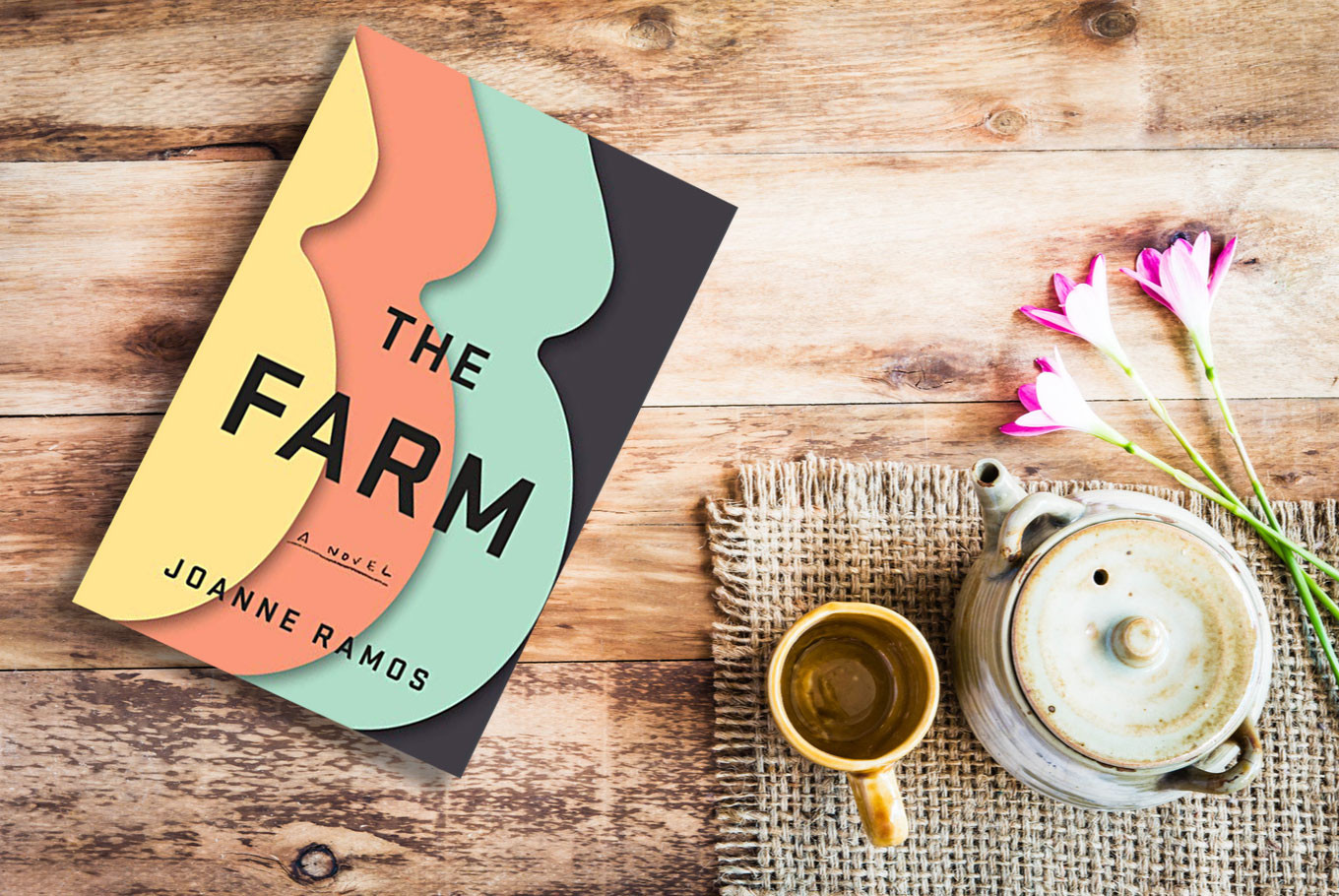

View all search results'The Farm' raises questions about surrogacy, commodification of women

Surrogacy in The Farm has been taken to another level, making the act of carrying a baby commercial and exploitative, reducing pregnancy to just another job and women to commodities. And yet, the job is crafted as a luxurious retreat and even meaningful.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

re you a woman and in need of a job? Try your luck at the Golden Oaks, where you will be given lavish accommodation with nutritious catering and various entertainment systems, in exchange for carrying a baby for wealthy clients.

This is the premise of Joanne Ramos' new book The Farm, a fiction published by Bloomsbury in May. However eerie that might sound, surrogacy has become a source of income for many women across the world, and less-generous and more-industrialized baby farms do exist in real life.

The Farm follows the lives of several women, all coming from various socioeconomic backgrounds whose fates are tangled up in the surrogacy business provided by Golden Oaks. Surrogacy in The Farm has been taken to another level, making the act of carrying a baby commercial and exploitative, reducing pregnancy to just another job and women to commodities. And yet, the job is crafted as a luxurious retreat and even meaningful.

The Jakarta Post talks to Joanne Ramos about surrogacy, the commodification of women in the late-capitalist system and the American Dream.

Where did the idea of The Farm first come from? Are you aware of the existence of real-life baby factories in India, Nepal and Ukraine -- among other places?

The Farm emerged from ideas that have consumed me for decades — ones rooted in my experiences, and the people I’ve come to know, as a Filipina immigrant to Wisconsin in the late 1970s, a financial-aid student at Princeton University, a woman in the male-dominated world of high finance, and a mother of three in the era of “helicopter” parenting.

Starting at Princeton, when I encountered huge disparities in wealth and privilege for the first time, I began questioning the story of America told to me by my parents: that in America, success is won by working hard and playing by the rules. This questioning came to a head when I began raising my own children in Manhattan. I hired a nanny for a time, and I got to know many other domestic workers at the parks and on play dates. Many of these women were mothers; some had left their kids back in the Philippines, the Caribbean and elsewhere and supported them by caring for other (wealthier) people’s kids in New York. The only Filipinas in my daily orbit then, in fact, were Filipina domestic workers. The gulf that separated their lives and mine — and their children’s opportunities and those of mine — could not be explained away by the American narrative of “meritocracy”.

It was this accretion of ideas and observations that spurred me to write the book I’d always dreamed of writing. The challenge was in finding a story to make these ideas come to life. After a year and a half of writing in the dark, I came across a short article in the Wall Street Journal about a surrogacy facility in India. The what ifs began pouring onto the page. What if I made the surrogacy facility a luxury one? What if the clients were the richest people in the world, intent on giving their fetuses a “head start” in utero? What if the surrogates were mostly immigrants..? I didn’t do any research — I simply began to imagine, and write, The Farm.

Even after all that happens, the main character Jane still feels grateful for her life and thankful for Mae. I can't help but wonder if gratitude is just another way to cope with massive class inequality and exploitation. What do you think? Another character, Reagan, even obsesses over the purpose of her pregnancy. Do you think that this obsession over purpose is just another tool to cope with the hyper-capitalist system?

No one has asked me this yet — and I am so glad you did!

I think every country has its foundational myth — the story told to its people to justify the economic and political system that exists. The American story is one about meritocracy, free trade, and capitalism as a “win-win”. This is the story that Mae Yu, the woman who runs The Farm, believes in. She truly does believe that, despite the inequality at The Farm, the system works for both surrogates and clients. The surrogates can earn big money and change their lives so long as they work hard and play by the rules. And the Clients get babies who are given every advantage starting in the womb. (This may sound crazy, but it’s only a more extreme version of the many ways wealthy people already pay to give their kids “the best” of everything.)

Every foundational story also has its supporting stories. I purposefully put references to both gratitude and the mantras of “self-help” in the book, because I think both are supporting stories. Gratitude is wonderful, and I do believe feeling a sense of gratitude contributes to a meaningful and happy life. I also think gratitude can be used to keep people in their places. Self-help mantras (“whatever you can believe and conceive you can achieve”, for instance) can be empowering. They can also put too much of an onus on the individual — implying that individual gumption and effort is all you need to “make it”, when in fact there are many situational and structural obstacles to success.

As far as “purpose” — people have searched for meaning since the beginning of time. I don’t think this compulsion is a product of a hyper-capitalist system. I do think that in a hyper-capitalist system, “purpose”, the desire for it, is commodified and used as a marketing tool — and many of us buy into it.

Read also: Alice Clark-Platts on 'The Flower Girls' and the beauty of evil

Another subplot is the experience of women immigrants, who, as reflected in Ate's story, have to leave their families in order to make money. At the other end of the spectrum is the rich businesswomen who chooses not to have kids, also to focus on making money. Do you think that motherhood and pregnancy are obstacles for women that have to be sacrificed for success?

The question of whether women can “have it all” — motherhood and career success/fulfillment outside of the home — is still unresolved because it is consistently framed as a question for women. As long as the question of child-rearing is primarily a woman’s concern, and not one equally shared and shouldered by their partners, and not one addressed by society at large (in terms of parental leave; equal pay for women; affordable childcare, and the like) — then yes. I do think that motherhood and pregnancy are obstacles for women’s “success”.

What are the most uncomfortable scenes, dialogues or thoughts you had while writing the book? Which character, if any, makes you most uncomfortable? Why?

The Farm is a response to our failure to see people who are different from ourselves. I know those who reflexively demonize anyone who works in finance or has a lot of money, for instance. And I know people who have never really “seen” the women who work in their homes — or who see them as noble or saintly, which is another form of not truly seeing.

I had no interest in writing a screed. Neither did I have any interest in populating the book with villains or saints. One of the big challenges in writing The Farm was to make each of the four narrators real and, in some way, understandable. I tried hard to create characters that reflect the complexity of real people. Real people have myriad, and often conflicting, needs, desires and loyalties. We try to balance them; often we fail; sometimes we betray each other.

As far as which character makes me feel most uncomfortable — honestly, I love them all, for different reasons. The most polarizing character is Mae Yu. The funny thing is that she’s not the only person in the book who betrays people, but she’s the lightning rod for a lot of criticism.

In many ways, Mae is the embodiment of the American Dream. Her dad is an immigrant from China; her mother is Caucasian. She grew up middle class and worked hard to get where she is — the first and only female managing director at the luxury-goods conglomerate which owns the Farm; the primary breadwinner of her family.

Mae is good to the people in her immediate orbit. She is helpful to her assistant, a young African-American woman who was once a host at the Farm, as well as her best friend from college, a public-school teacher in Los Angeles living on a limited salary. And yet, Mae runs a business that manipulates and commodifies women.

Some readers have accused me of “whitewashing” Mae, whom they see as villainous. Here is the thing: I aimed to make Mae complicated — neither wholly good, nor wholly bad — because I wanted readers to grapple with their feelings about her. The Farm is not a comeuppance story. It was meant to reflect the world.

Also, I’d hazard to guess that many readers know someone like Mae, if in a much milder form. I made Mae (her job, her role) extreme — in the way that Golden Oaks is an extreme version of our world and economic system. But I bet most readers have at least one person in their lives whom they feel has compromised his values for lifestyle or job or necessity — say, the friend who works at a university with an endowment invested in oil companies; the banker who does deals for pharmaceutical companies that make opioids; the museum that accepts donations from pharmaceutical companies that make opioids.

In the author's note, you mentioned that you wrote this so people could question further who they are. What do you discover about yourself after writing this?

One of my hopes in writing the book was less that a reader might understand herself better, but that she might see someone different from herself more clearly. I think we often fail to truly see people around us — particularly if they are unlike us. We too often and too quickly label each other and then see the label, not the person. I’ve straddled many worlds in my life. I’ve seen and felt and made judgments from both sides of various divides, whether across the divide of privilege and money or the schisms of motherhood. If the book has reinforced anything for me, it is the importance of not simplifying people. (wng)