Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results‘They call me baboe’: How a domestic helper saw the colonial world

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

S

he was a happy girl aspiring to be a teacher when she decided to leave her home village. Thus began the story of a girl, about 20 years old, from Central Java who went to Bandung in West Java to work for a Dutch family.

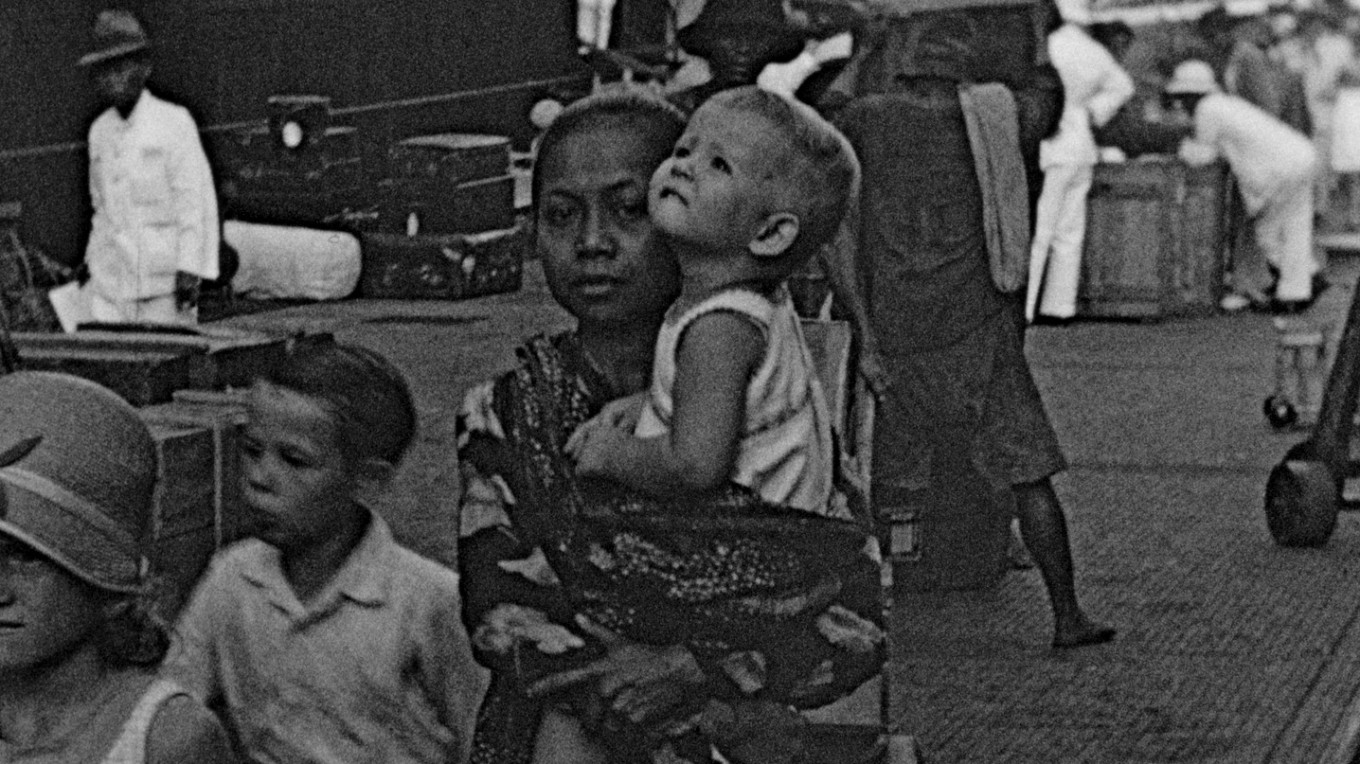

And it’s there — in a totally different social milieu, living with a Dutch family with five children, in which she had to take care of the youngest, a boy called Jantje — that she came to realize the various worlds she went through ever since.

First, through the world of the family she lived with, amid the Dutch community; next, the Japanese occupation, and then the fight for independence (1939-1949). It resulted in a complex relationship between her and the family.

The film Ze Noemen Me Baboe (They Call Me Baboe, 2019) is a fictional story of Alima, who seemed to enjoy her life in the colonial world, which she had never been a part of.

That life that was not quite hers, was the everyday life of caring for a child whose mom and dad were both the bosses of the family and her country.

However, she served them loyally — indeed she called them keluargaku (my family). That life that brought her on a family trip by ship via Egypt to the Netherlands. But when she returned to Java, it was only to see that the family she had served for years had been taken by the Japanese to a prison camp.

What was left for her was a different world yet again. Now she had to bow her body in order to respect the passing Japanese military and watched the local youth training the Japanese forced them to join.

What a journey of life; one, indeed, that made her increasingly conscious of her identity status.

In Java, she was accustomed to serving the family as her boss. Once in the Netherlands, she was taken by surprise, not knowing what to do, when in a shop she was kindly addressed with U (you, respectfully, in Dutch). Here, in her boss’ own country, she was treated as an equal.

Back in Java, as before, she watched the children play happily and the parents enjoy their privileged life when she and other Indonesians went through quite a different life as servants.

“They live a life as if the world is theirs,” she told her mother.

Her conclusion, thus, defines the very nature of her being a baboe — a Javanese-turned-Dutch-colonial institution that survives to this day, albeit in various forms.

Change came when her “family” was put in a Japanese camp, leaving her to find another job and her lover, Riboet, found death in the struggle for independence.

Caught between nationalism and loyalty, she cried when her “family”, once out of the camp, was taken aback to see Indonesians now ruling the country.

“No, we didn’t rob the country, we took it back!” Alima explained forcefully.

The story is fully narrated in her perspective as told to her mother and vividly illustrated with painstaking selection of hundreds of archived films.

She was typically called baboe, someone who takes care of the boss’ children. The term, however, later refers to domestic helper in general. It apparently comes from the words mbak (sister) and ibu (mother) combined.

Oddly enough, though, the film seems to evade the pejorative term inlander — the native world of which baboe is part and parcel.

The filmmaker, Sandra Beerends, should be applauded for her work and achievement. The film, spoken in Indonesian with Dutch translation, is screened as part of the 2019 International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA).

The writer is journalist residing in Amsterdam