Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

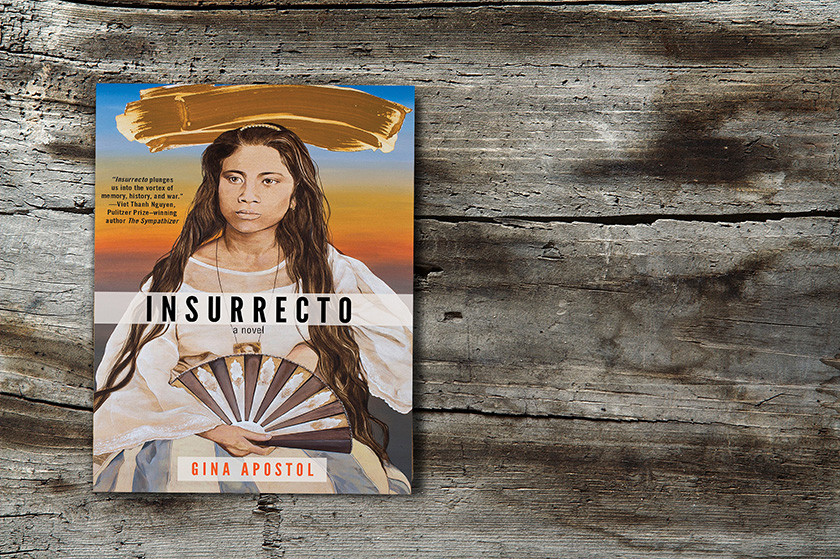

View all search results‘Insurrecto’: A postmodern lens on conflicting histories

Filipino novelist Gina Apostol’s English-language novel is accessible and relevant to readers in Indonesia.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

woman returns to her birthplace, Manila, carrying a heavy box of vinyl records and a suitcase full of books. She is a translator. Her name, Magsalin, simply means “to translate” in Tagalog. And yet she has returned to the Philippines to write her own detective story – “to soak in the atmosphere, to check out a setting, to round out a missing character, to find the ending”.

This is how the plot of the 2018 novel Insurrecto by Filipino author Gina Apostol begins.

I came across the book not in Manila but along the shelves of POST Bookshop in South Jakarta. As I scanned countless back covers, it was this novel’s broader premise that first caught my eye: an American filmmaker disappears on the island of Samar in the Philippines in the 1970s.

He had been shooting a movie based on the atrocities the United States committed against Filipino communities following an attack by local revolutionaries on American soldiers in Balangiga, Samar, in 1901.

The filmmaker’s daughter, Chiara Brasi, arrives in Duterte’s Philippines decades later to make her own film on the same massacre and hires Magsalin as her translator.

Indeed, it is Chiara whom Magsalin chooses as the protagonist in her mystery novel – that is, before Magsalin ditches the project altogether to write her own version of Chiara Brasi’s film script.

Tracing history: The 'New York Times' calls Gina Apostol “a magician with language” in her novel 'Insurrecto'. Her most recent work uses her research on the Philippine-American War to cast a lens on our contemporary times. (Courtesy of ginaapostol.com/-)In a novel about who writes history and how, Apostol tackles a double narration of violent political conflict across Filipino history, from colonialism, through Marcos’ US-backed, anticommunist military dictatorship and into the present context of increasingly illiberal democracy.

As much as the mysterious opening chapters of Insurrecto are steeped in the atmosphere of the bowels of Manila’s shopping malls, the book also seemed to resonate in the context of the Jakarta market where I stood browsing.

In Indonesian literature, representing the collective trauma of past conflict is not uncommon. A range of authors – from the globally well-received Eka Kurniawan and Laksmi Pamuntjak to up-and-coming voices like Felix K. Nesi and Anindita S. Thayf – structure their works around histories of violence.

Given that Filipino literature is often published in English, novels like Apostol’s Insurrecto provide English-language readers in Indonesia a unique opportunity to access foreign approaches to familiar topics from another Southeast Asian archipelago.

But it is not just these broad comparisons that make Insurrecto specifically relevant in Indonesia. Apostol’s unique double narrative perspective between translator and author, as well as her preoccupation with postmodernism, connect to more specific concerns in Indonesia’s cultural scene.

In the competing narratives between foreign author Chiara and local translator Magsalin, tensions between interpretations of history across cultures shape the novel’s dual structure. That tension is first apparent in the characters’ earliest interactions, for example, during a debate over specific word choice:

“She had a conversion into the world of the Filipino insurrectos of 1901, Chiara says.

That is not the correct term, Magsalin says.

What?

They were revolutionaries, Magsalin says. It was not an insurrection.

Chiara ignores her.”

In this simple interaction, Chiara presumes ownership over Filipino history by snubbing Magsalin’s correction, and so Apostol highlights the fraught dynamics of a Westerner representing – or appropriating – historical trauma in a post-colonial context.

Through this attention to the language of narration, Apostol flips the focus of her novel from Filipino history to the individuals carrying out the act of representing that history.

Apostol’s literary critique of translation and its pitfalls are useful points for reflection in Indonesia, where the foreign-directed film The Act of Killing is arguably the most globally recognized cultural product about atrocities like the 1965 mass killings. As important as this award-winning documentary is, the question of who stands behind the camera and the implications of that perspective on representation merits reflection.

As an American who writes about Indonesian literature, Chiara’s cavalier attitude toward her choice of words makes me pause – especially when I notice that Apostol allows Chiara’s choice of words, not Magsalin’s, to define the novel’s overall title: Insurrecto.

Moreover, the way the title Insurrecto plays on a debate between two characters also emphasizes that the novel is a constructed story. Other such reminders sprinkle the text from start to finish: the book begins with a “cast of characters” as in a film script; the chapters in each section are out of chronological order (Part I begins with chapter 20, before continuing onto chapter two); and chapter titles include meta-reflections on storytelling like “There Is Always An Alternate Story” or even questions interrogating the novel’s setting, like “Why Samar??!!”

In these meta-fictional, fragmented approaches to storytelling, Apostol opts for a postmodern lens in representing conflicting histories.

Some prominent Indonesian cultural critics question the relevance of postmodernism in countries like Indonesia.

Wijaya Herlambang, for example, discusses the limits of postmodernism in his analysis of narratives about the 1965 mass killings in cultural production. The framework lacks relevance to class structures in Indonesia, he argues, because class still functions more along labor lines than the Western model of a silent majority passively consuming media.

And yet Apostol chooses to apply a fully postmodernist frame to a very similar historical question in a neighboring, postcolonial context. It is these subtle disjunctions and wider parallels between this Filipino novel and Indonesian cultural concerns that makes Insurrecto such an interesting read for those acquainted with Indonesia.

On the pages of Insurrecto, I found a work of English-language literature that places Indonesian concerns in a regionally comparative context. Read by an American living in Jakarta, Insurrecto uncovers the transnational implications of national histories and functions as a lens into a geographically proximate, literarily compelling fictional world. (ste)